A country built to last

Every day is a new mess. Who's looking past the weekend?

“Stop calling academics, Paul,” my old Montreal Gazette bureau chief Terrance Wills told me one afternoon a lifetime ago. “All they do is read our stuff and tell us what to think.”

Terry didn’t give me much advice, so I took this tidbit to heart. The ritual of adding three paragraphs of comment from a political scientist soon vanished from my workday. Political science is honourable work, but it doesn’t often have much to say about the day’s headlines. That’s not what it’s built for.

But as it happens, this newsletter isn’t always built to obsess over the day’s headlines either, so today I’m going to share thoughts on a recent speech and a new paper that share a theme: the decline of coherent, thoughtful public administration.

Adaptability and its absence

I mentioned in the weekend’s post about that big COVID-19 conference that Alasdair Roberts had delivered a keynote address. Here’s his biography. He’s Canadian, but from 2017-22 he was the inaugural Director of the School of Public Policy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he continues to teach. He’s written six books since 2010, a prospect that exhausts me.

If all Roberts had done was say some more about COVID at a conference about COVID I wouldn’t trouble you with him. But he talked instead about how governments, and the countries they serve, last by adapting to changing circumstances. Or how they don’t. In short, Roberts delivered a warning against short-termism. The text of his keynote is available here as a .pdf.

Roberts is interested in a property he calls adaptability, which will be the topic of a new book (!) next year. Countries have it and survive, or they don’t and they fall apart and reconstitute under different political arrangements. Canada is “actually one of the older states existing in the world today,” he notes.

An adaptable country does four things well, he says. Forward thinking to spot long-term threats; inventing strategies to forestall such threats; legitimating those strategies, or building public support for them; and execution, or turning strategies into successful action.

Canada’s actually done well on these fronts for much of the last half-century, Roberts says. “In fundamental ways, Canada is a different country than it was 40 years ago.” It’s added 15 million people, which is “like adding another Ontario and another Quebec;” it’s expanded the protection of individual rights and shifted power from Ottawa to the provinces; and it’s begun “the work of acknowledging the rights of Indigenous peoples.”

So far, so laudable. But a lot of the changes Roberts lists date from the 1980s or extend trends that started there. And their net effect is to make the country more decentralized and complex: Harder to run, essentially.

What’s changed? Roberts, who worked as a Progressive Conservative staffer in Ontario before becoming a full-time academic, delivers an ode to the olden days, defined roughly as the last two decades of the 20th century. “One of our advantages was that we worried constantly about the country’s future,” he says. That’s one way to put it. And Canada “relied heavily on royal commissions and independent advisory councils.” It’s what Roberts and his colleagues sometimes call maintaining a healthy public sphere. These days? It’s weird that in a million-channel universe, it feels like those common spaces are harder to find, or harder to respect when you find them.

Roberts identifies four current threats to Canada’s adaptability. One is a reversion toward short-term politics,” along lines I discussed here. The second is a decline in “the health of our national conversation,” by which he mostly means social media, which I discussed in this podcast episode.

Roberts’ third threat is a “deterioration in the quality of dialogue among our country’s leaders.” He notes, intriguingly, that Justin Trudeau meets his G7 counterparts more often as a group than he meets provincial premiers as a group, and indeed this has been true of Canadian prime ministers for decades. (The PMO would rebut this by mentioning Trudeau’s weekly Zoom calls with premiers through the COVID pandemic. I would find that example unpersuasive, but for now let’s move on.)

His fourth threat is the health of the public service, which gets mentioned all the time around Ottawa. Here, he sees risk aversion not as a problem in itself but as a symptom of a bigger problem, which is the multiplication of checks and controls on the public service. The goal is greater accountability. The effect is to destroy initiative and morale.

The remedies Roberts suggests for these ills are straightforward: more royal commissions and similar stock-taking exercises, which is what I suggested when this little arc of newsletter posts began; the establishment of “publicly funded party institutions” to help political parties come up with sound policy proposals between elections; and action on Donald Savoie’s call for a royal commission on the condition of the federal public service.

I’ll be curious to read Roberts’ book when it comes out. His speech strikes me as more impressionistic than methodical, and I can already hear the objections to every point he makes. I’d raise the odd objection myself. I know the PMO would. One suspects they’d say that when they make huge investments in programs, compensation and consultation in Indigenous communities, they’re engaging in precisely the sort of long-term thinking Roberts wants. They’d probably say the same for a string of budgets devoted to the so-called energy transition.

But I’ve written so often in ways that echo Roberts that you won’t be surprised to learn I think he’s onto something. Of course it’s still true that governments think about the future. But it’s also true — I think it’s obvious — I think it’s a really big problem — that in a city where important emails go missing or unread, where the PMO’s issues-management staff obviously has far more political clout than almost the entire cabinet, the long term is not where this government’s heart lies.

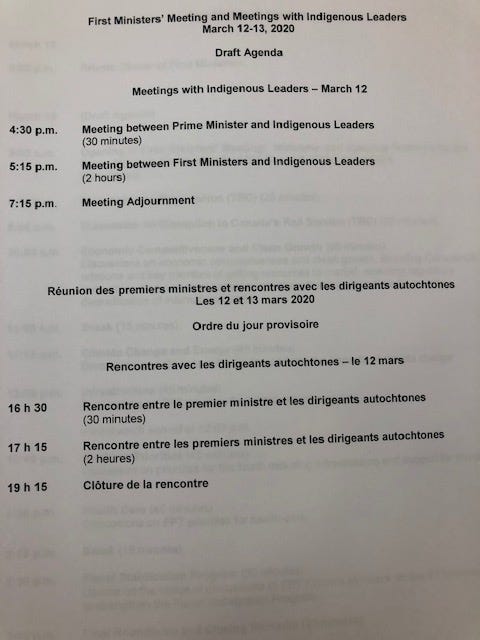

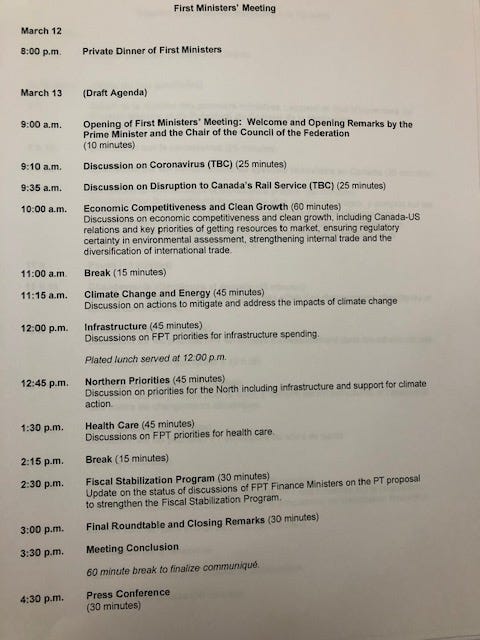

Here’s a little scoop that’s calcified into history. When the COVID lockdown began in March, 2020, Trudeau and the premiers were scheduled to welcome the premiers for a first ministers’ meeting in Ottawa two days later. It got cancelled. This was going to be the agenda for that meeting.

At the time, the reason why I asked a provincial source to cough up the agenda was because I was astonished that, until at least Wednesday of that week, the PMO apparently still expected a meeting with the premiers could mostly be about other things besides COVID. This agenda confirmed that suspicion. Flipping from “hypothetical” to “really immense crisis” always has been hard for this government.

But in retrospect, what strikes me about this agenda is that I actually can’t imagine Justin Trudeau or Pierre Poilievre hosting colleagues for a meeting with a comparable agenda again. Two and a half hours with Indigenous leaders? A string of open-ended discussions on public-order disruption, "climate change and energy,” infrastructure and health care? It just sounds like so many hostages to fortune that in the current environment, no PM’s chief of staff would advocate such a thing. Hey boss, invite the premiers to town. You’ll be outnumbered for a day and a half, tops!

The amazing spectacle of February’s health-care meeting, where Trudeau simply summoned the premiers to Ottawa so he could read them a news release about how much money they’d have to live with, looks like a far likelier model for future meetings, however few and far between. Basically nobody in today’s politics is comfortable with a situation in which they’re not sure what other people will say. So yeah, I’d say Roberts is describing real problems.

Reviewing the review

Here’s a new paper — newly published this week — from Evert Lindquist and Robert Shepherd at the University of Victoria and Carleton University respectively. (I do apologize for how today’s post is all dudes. I’m definitely looking forward to Penny Bryden’s history of the PMO, for what it’s worth.)

Lindquist and Shepherd examine, in effect, a subset of what Roberts is describing. How do governments govern well if they don’t evaluate the effectiveness of their spending? And what healthier way to ensure good habits in the future than by periodically examining existing spending for smart savings?

Concretely, Lindquist and Shepherd examine a Trudeau Liberal platform commitment from 2021, a “Strategic Policy Review” designed to save billions of dollars. The best that can be said for this project is that the government keeps mentioning it, which isn’t quite the same as doing it. Given scant evidence from these periodic mentions — in the 2021 fall update and the 2022 and 2023 budgets — they conclude: “The review of program spending will likely be sporadic, untargeted, and lead to across-the-board cuts to achieve the 3% reduction.”

I’m delighted to read about their skepticism, since I suspected the strategic policy review would be a farce as soon as I read about it, in the Liberals’ 2021 election platform. I wrote at the time that it was “nearly satirical” for the Liberals to promise greater efficiency in a platform with 182 chapters that promised massive duplication of previous efforts.

What’s sadly ironic, Lindquist and Shepherd write, is that Canada actually used to have a reputation for serious program review. Which doesn’t mean every previous exercise was covered in glory. Brian Mulroney put his Deputy Prime Minister, Erik Neilson, to the task in 1984. “The work was intense: three teams submitted reports covering over 25% of the programs by March 1985, all reports were submitted by December 1985, and the Deputy Prime Minister tabled the final report along with 21 volumes in March 1986, 19 months after the [review process] had been struck.” But few of the Neilsen task force’s recommendations were implemented. It didn’t fit the mood of the times.

Jean Chrétien had better luck with his 1994-96 program review, precisely because the mood had changed, and getting control of public finances had become a life-or-death test of government competence. Lindquist and Shepherd point out that one reason for the success of the Chrétien review was precisely that it didn’t propose across-the-board cuts, which inflict cuts without regard for whether they’re manageable, while missing opportunities for bigger structural change elsewhere.

A decade later, Chrétien and his former Clerk of the Privy Council, Jocelyne Bourgon, were frequent visitors to Paris, where a new French government was eager to copy the Canadian success. A senior Canadian public servant even embedded in the French finance department. It didn’t work. When asked how he’d done it, Chrétien said, “You have to do it,” which was interpreted as buffoonery by his hosts, but what he meant was, if you don’t take the exercise seriously, then the “how” won’t matter much.

Lindquist and Shepherd say much the same thing, more politely. “A more transparent, forward-looking, and comprehensive spending review” than the one Trudeau is rolling out “could have been advisable over the last year, perhaps leaning more towards the scope of the 1984–86 and 1994–96 spending reviews,” they write. Especially in the wake of the vastest, fastest and most hectic increase in government spending since Confederation.

But even as they’re suggesting it, Lindquist and Shepherd admit this isn’t the kind of world where such exercises have much hope. “Such reviews not only need strong ministerial support and central coordinating capacity,” they admit mournfully, “but would also be ripe for critical commentary in today's social media environment.” Boy, I’ll say.

Lindquist and Shepherd end up recommending a sort of dollars-and-cents version of the post-COVID stocktaking I recommended last week. Canadians and their governments, those of us who’ve survived, have just been through a very large shock to the system. Does muddling through really make sense now? Does a continued reliance on crisis control, in the form of issues management as the dominant reflex of government, really make sense? Is it impossible to imagine something more methodical, insulated from the influence of the people who’ve been running a permanent campaign for most of a decade?

Housekeeping note

Last summer I wrote a series of posts on essentially partisan considerations — would Trudeau stick around, could the Liberals pull out of a spiral of lousy decision-making, and so on. This summer I plan to concentrate less on tactical considerations and more on the system we find ourselves in. Why are so many people working in communications, yet so few people know what’s going on? What happens after big news organizations lose their gatekeeper role? I’ve been procrastinating on these topics, or writing around their edges, for a year. Time to get cracking. This exercise will span several posts and take probably a couple of weeks to roll out, starting next week. If you think writing like this deserves support, please tell a friend…

… or consider becoming a paying subscriber.

Road stories

Of course there will be pauses for other topics. On that note, I want to remind people that Caity Gyorgy, the formidable young jazz singer I wrote about in April, will be performing in Winnipeg, Medicine Hat, Ottawa, Calgary, Victoria, Vancouver, Edmonton, Saskatoon and Montreal over the next three weeks. If you go to the Ottawa show on Saturday I’ll see you there.

The Hon. Senator

A postscript.

On Monday I got an email from Ian Shugart. This is a welcome occasion when it happens. Shugart was Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs before he became Justin Trudeau’s third Clerk of the Privy Council in 2019. Serious health problems made him take a leave from that post, but last autumn he had recovered enough for Trudeau to appoint him to the Senate. Shugart and I were also named Fellows at the Munk School at the University of Toronto; a public interview we held in front of an audience at Munk, and a wide-ranging dinner chat afterward, constituted some of the best Ottawa shop talk I’ve ever had. But his health took another turn for the worse, which is why he’s been absent from the Senate. He was writing to tell me he would finally speak on Tuesday. His maiden speech in the Senate chamber.

His remarks were in line with everything else I’ve written today. These are strange and consequential times, he said. “To survive, to say nothing of excelling, in such an environment, we must be at our best. … If there’s a domain where we must do better, it’s that of governance and politics.”

As good speakers must, Shugart had an anecdote. In 1981 Pierre Trudeau asked the Supreme Court to tell him whether he could patriate and amend Canada’s Constitution without provincial support. The Court responded with a kind of Zen riddle: what Trudeau wanted would be legal, but not constitutional in the sense that it would flout convention. That was enough to send a very grumpy Trudeau into yet another federal-provincial conference, which produced the consensus that had escaped governments up to then. (Quebec’s government dissented from the consensus. A story for another day. Thousands of other days, as it turned out.)

“Honourable Senators, Mr. Trudeau acted with restraint,” Shugart said. Again, I know people who’d debate that assertion, but he was in a debating chamber after all. And then: “Colleagues, I have to ask whether either of the main party leaders today would act with such restraint.”

His next example of restraint, perhaps surprising, was Ontario premier Doug Ford, who withdrew a plan to use the Charter’s “notwithstanding clause” pre-emptively in a confrontation with teachers’ unions. It was the willingness to retreat, not the original plan, that drew Shugart’s praise. “To his credit, Premier Ford acted with restraint.”

Shugart’s main message of the day was to his colleagues. More and more of them, now a majority, were appointed by Justin Trudeau, notionally non-partisan but generally sympathetic to the Trudeau government’s goals. What will happen if the government’s party stripe changes? “We could ultimately be left with many Senators effectively setting themselves up as an unofficial opposition.” It would be a recipe for “perpetual or frequent standoff,” even “legislative paralysis.” In such a confrontation, the prerogatives of each Senator would be “black-letter law,” but its full exercise wouldn’t be legitimate because Senators aren’t elected.

“An essential ingredient in resolving such a crisis will be the practice of restraint,” Shugart said.

I’ve written a lot already today, so all I’ll add was that it was good to see him.

Thank you for drawing attention to Ian Shugart and his characteristically understated, concise, and wise advice to today's policy-makers. Enormous contributor. First met him when he was helping Henry Friesen engineer the transformation of MRC into CIHR. As ADM, he was the Sherpa for the National Advisory Committee on SARS & Public Health and the machinery that flowed from it. Stayed in touch sporadically during his DM incarnations and then often during the darker days of COVID-19 when he was Clerk of the Privy Council and so clearly a voice of reason in Ottawa. That's the little I know -- one person's tip of the Shugart iceberg. A remarkable public servant and a great Canadian. And yes, a man who then as now, preached and practised reasoned restraint. What worries me is how old-fashioned those virtues seem in the endemic craziness of our time.

I have always been grateful to know Ian Shugart as a friend and colleague, ever since we were ADMs together and, as he would probably hasten to recall, we had to attend monthly 8:00 am meetings with PCO and a passel of other ADMs to debate how many angels could dance on the head of a pin called the Precautionary Principle.

But for me the true measure of Ian Shugart as a human being was seen when he was newly arrived as DM at ESDC in 2010. A senior ADM in the department had just died very suddenly and unexpectedly. Ian flew to Cape Breton to meet his family and represent the public service at his funeral, and then convened an all NCR staff memorial in Gatineau where he spoke with the perfect blend of anecdote, respect and hommage of someone for whom he felt a deep institutional responsibility.

I keep him in my thoughts and hope he regains all his strength.