What ails us

There's no political reward for fixing what needs fixing. So it doesn't get fixed.

Let’s discuss why our government doesn’t work so well, why it’s not likely to work better soon, and why our politics is so radically ill-suited to the task of fixing our government. I’ve felt for a while that, as a reward for your early support for this newsletter, I owe you something substantial on these subjects. This is it. Settle in.

1. Life on the slopes

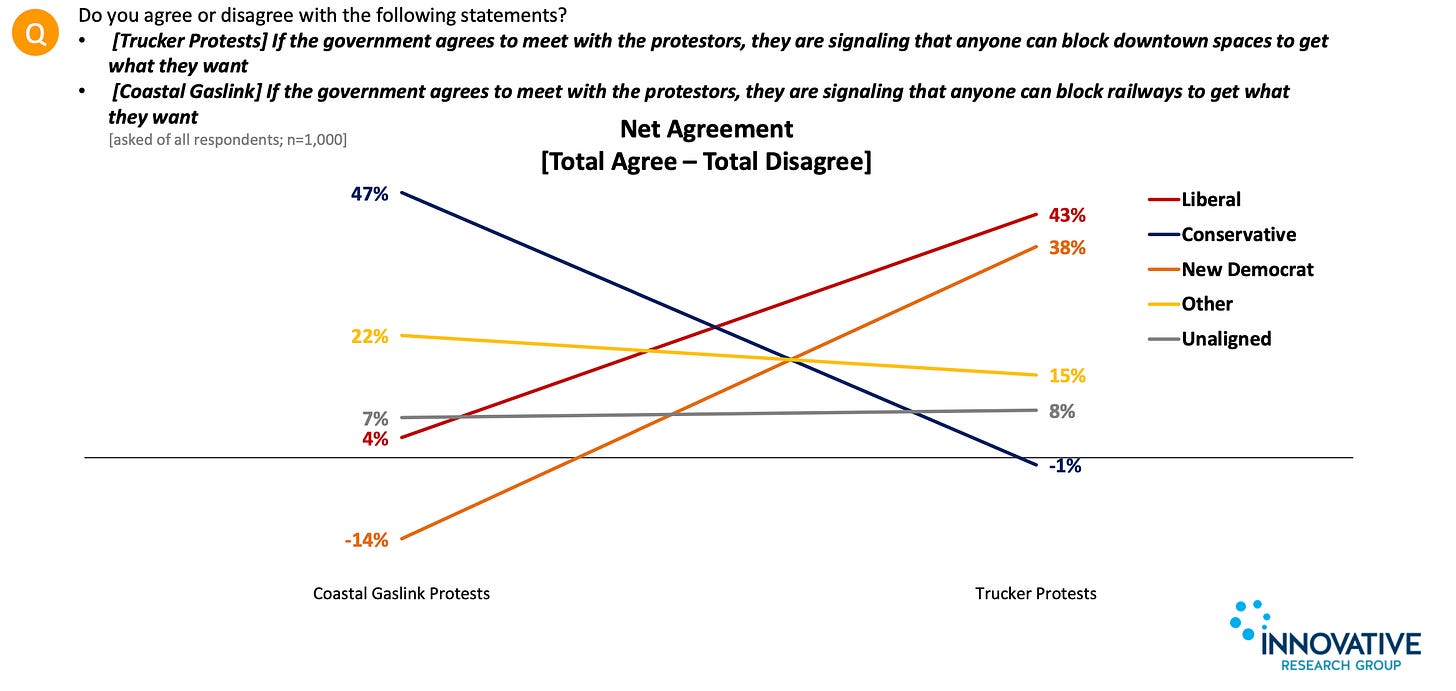

This graph is the best illustration of Canadian politics I’ve seen this year. It comes from Greg Lyle, the pollster who runs Innovative Research Group. He published it in February when downtown Ottawa was full of trucks. It takes some explaining, but we have time today.

On the left are results from a poll Lyle did in 2020. Rail blockades and protests had flared up across Canada, in support of Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who opposed the Coastal GasLink pipeline project. One of the questions Lyle asked in 2020 was, Do you agree or disagree that “If the government agrees to meet with the protestors, they are signaling that anyone can block railways to get what they want”?

On the right are results from a poll Lyle did two years later, in March of this year. Agree/disagree, “If the government agrees to meet with the protestors, they are signaling that anyone can block downtown spaces to get what they want”?

The graph tracks opinion on these questions by stated political party support. People who said they’d vote Conservative were net 47% positive on the 2020 question: When asked whether meeting with train-blocking, pipeline-opposing, Indigenous-solidarity-proclaiming protesters would encourage just about anyone to block railways, there was a 47-point gap between Conservative supporters who said “Yes” and those who said “No.”

Another group of Conservative supporters was much less likely in 2022 to agree that if the government met Ottawa-blockading, vaccine mandate-opposing, fed-up-with-restrictions protesters, such a meeting would open the floodgates to all sorts of similar chaos. In fact, subtracting “disagree” from “agree” produced a score of -1. By a hair, Conservative supporters in 2022 saw no Pandora’s box in a hypothetical meeting between feds and convoy.

You can read the rest of the graph now. Liberal supporters, net +4% on meeting with Coastal Gaslink supporters in 2020, pretty Zen; net +43% two years later on whether meeting the convoy would unleash demons.

The biggest swing was among NDP supporters. On balance in 2020 they were sure, at -14%, that meeting Coastal Gaslink protesters wouldn’t inspire copycats. And even more sure, +38%, that a government meeting with the Freedom Convoy in 2022 would invite further chaos.

So: Partisans mood-swung like a barn door when faced with two different but comparable situations. And they swung in characteristically partisan ways, with Conservatives showing more sympathy for the truckers than the pipeline protesters, Liberals the opposite, and New Democrats the most opposite of all.

Here’s what I like the most about all this. The question at hand — if government meets with this week’s protesters, will it encourage similar behaviour from other protesters? — actually isn’t inherently laden with value judgments. Respondents were never asked whether they liked the protesters, just whether meeting with them would spur other protests. You could answer Yes but still think a meeting would be worthwhile. You could answer No but still think the protesters didn’t deserve a meeting. You were allowed to believe that meeting protesters would encourage protests — and that would be a good thing, because Canada just generally needs more protests. And even though the Freedom Convoy and the GasLink blockers were different groups acting for different goals, it would absolutely have been possible to answer the same question the same way in each case.

In fact, some people did. And they’re the people our politics are now designed to ignore.

In addition to NDP, Liberal and Conservative supporters, Lyle tracked opinions of people who support other parties. That’s the yellow line above. It’s nearly useless, a jumble of Green, People’s Party, Bloc Québécois and who knows what else.

But he also tracked responses of people who didn’t express support for any political party. That group’s responses didn’t swing at all between 2020 and 2022. That’s the black line above. Does meeting protesters encourage protests? Sure, on balance, a bit, these non-aligned voters said in 2020 (net +7%). People like them said the same thing in 2022 (net +8). Call this group the people who don’t freak out.

Now. Who gets heard in our politics? It goes without saying that the people in political parties, including the people in governments formed by political parties, are partisan. Liberals will tend to be on that upward-sloping red line in our graph. But what’s more important is that these days, only the people on the steeply-sloping partisan lines pay for our politics.

Since 2011, individual donors are the only source of funds for Canadian federal political parties. Corporate and union donations were eliminated in 2006. Public per-vote subsidies were eliminated in 2011. Today the only way I can pay my political party’s bills is if I can persuade lots of people like you to give me many small sums of money. And the people on that nice, even-keel, non-sloping black line in our graph? The people who don’t view every sparrow that falls as a little morality play about their heroes and the villains they face? Those people will never give anyone a dime. It’s the people who mood-swing wildly — who think our gang is great and their gang is the demon — who can be provoked into donating, again and again, until they max out for the year, and then again starting in January.

Irving Gerstein, the Conservative Party’s chief fundraiser under Stephen Harper, explained all of this in a 2013 column by Ken Whyte that stands as one of the most important documents for understanding our times: “Message creates momentum creates money.” Parties that reside permanently on the sloping lines of a Greg Lyle poll — that think, talk and act like their most fervent supporters — are able to separate those people from their money. Parties that exit the slope for the level meadows of moderation go nowhere.

When Gerstein spoke, only the Conservatives had figured out how to work the system they had invented. The Liberals have long since caught up. With the Conservatives turfing a leader every two years, then sending the new leader out to be defeated so the cycle can repeat, both major parties have been on constant fundraising high alert for longer than Justin Trudeau has been prime minister. And both function by confirming their supporters’ worst fears. All the time. Each is trapped inside the two-dimensional phantom zone of a fundraising letter. Paul, you’ll never guess what those Conservatives are up to now! Will you send us some money so we can build a better, fairer Canada?

So Canada’s house is now perched, in perpetuity, on the slopes of Lyle. The best a few partisans can hope is that a truly wild election campaign might finally succeed in blowing the house off the red slope… and onto the blue slope.

And yet, so much of what ails us is immune to strictly partisan appeal. Which means that, in the eyes of governments that live on slopes, some big problems don’t exist because there is no financial or electoral reward for noticing them.

This is a long essay. Three-quarters of it lies below this paywall cutoff. The rest is for paying subscribers. I’d be grateful if you’d become one.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paul Wells to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.