Weather this week is warm but rainy in much of Costa Rica, where the Trudeaus are enjoying a summer vacation. Everyone gets a vacation, is this corner’s firm policy on such matters. The big question is what he’ll do next.

Justin Trudeau often uses his vacations to do some planning. Or before he leaves, he tells his staff to do some long-term planning and have options ready when he comes back.

Results are usually mixed. His winter 2016-2017 vacation produced a major cabinet shuffle (Chrystia Freeland to Global Affairs, a response to Donald Trump’s election) and a damning ethics commissioner’s report. His 2018-2019 vacation produced a major cabinet shuffle (Jody Wilson-Raybould to Veterans’ Affairs, a response, legend has it, to something Scott Brison did) and a damning ethics commissioner’s report. His vacation after the 2021 election produced a Speech from the Throne, a necessity after every election, and an apology.

What might be on his mind this week? More broadly: What’s changed in the eight months since his last Throne Speech that should require a prime minister’s attention?

Oh, lots.

A savage war in Europe. Instability in the Asia-Pacific. The highest inflation rate in the lifetimes of Karina Gould, Sean Fraser and Kamal Khera, the Trudeau cabinet’s youngest ministers. Three simultaneous inquiries into Trudeau’s unprecedented invocation of the Emergencies Act. Figure at least two of those will end badly. The emerging certainty that Pierre Poilievre will be the next Conservative leader. The worst polling numbers for Trudeau and for the country’s direction since he became prime minister. A promised China strategy that’s vanished and was, at any rate, apparently an exercise in missing the point. Delay on old promises. Public-relations fiascos in venues where the Liberals used to expect the benefit of the doubt. Signs of caucus unrest. The sort of headlines about feckless and even callous management that should be more surprising than they’ve been lately.

There have been some successes. Getting the Pope to apologize for residential schools on Canadian soil seemed impossible as recently as last year. Changing US “buy American provisions to read “North American” is an important trade win. But the bigger trend lines are ominous, and did Trudeau really rush to re-election for this?

At times like these, the PM’s supporters like to mention something else that’s new since the beginning of the year: the Liberal-NDP deal on confidence and supply that could ensure the Trudeau government’s survival until 2025. That would ensure three more budgets for the Liberals to restore public confidence, deliver on promises, ride out economic storms, and otherwise survive to fight another day. The deal is held together by nothing more solid than both parties’ willingness to stick to it, so it could fall apart any time. But say Trudeau gets two more years out of it. A lot can change in two years.

Except it’s worth remembering that a distant political cousin of the Trudeau Liberals — the Quebec provincial Liberals under one-term premier Philippe Couillard — were crushed in an election, more than three years after the budget cuts that made them unpopular. Couillard didn’t just lose, he may have lost beyond Quebec Liberals’ ability ever to climb back. Quebec voters seem to have made a decision early in his mandate, then waited patiently for a chance to implement it.

I’m out of the business of predicting election results. Elections are inherently unpredictable events. But I honestly don’t believe Trudeau is sitting on a beach, being pelted by rain, thinking, “I’m two years from having to worry about any of this stuff.”

So how does he turn his government’s fortunes around?

I’ve been speculating about the PM’s thoughts and options frequently here, because (a) subscribers seem to like it! (b) he’s been acting less and less like the Trudeau who won a majority in 2015. To the point when I’m kind of wondering when he’s going to give his head a shake.

Trudeau seems intent on illustrating the business-school distinction between “disruptors” — new, agile firms that win with surprise; and “incumbents,” big old firms that squat on a market segment they’ve owned forever and hope to keep swatting away new entrants indefinitely.

The outcome of such confrontations is hardly foreordained. The reason we’re still talking about how the rodents finished off the dinosaurs is because it was such a surprising result. The dinosaurs had a really good run for that first quarter-billion years. Incumbents have advantages, which helps explain why Trudeau, like his predecessor, was able to parlay an initial victory into two re-elections. “What are you gonna do, cancel your Rogers account?” turns out to be a good campaign slogan, most days.

But the Trudeau of 2015 would not have recognized the Trudeau of 2022. And he’d have been startled and embarrassed at the spectacle of the hidebound, defensive stick-in-the-mud he has become.

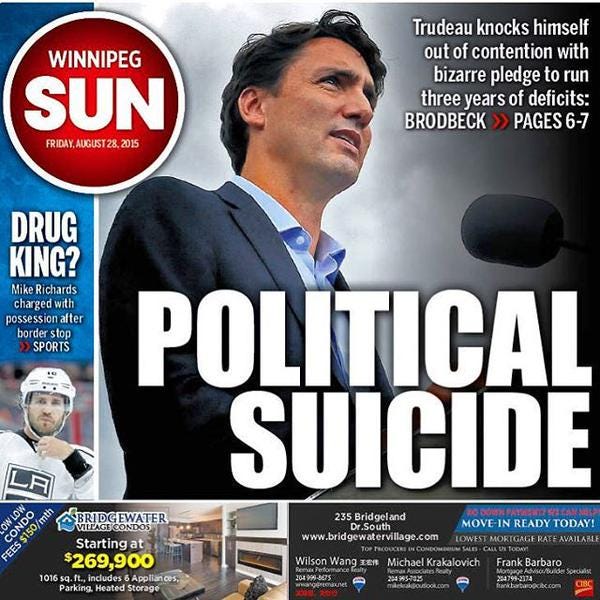

The younger Trudeau was full of surprises. Like him or not, at least he was frisky. Kick all senators out of the Liberal caucus. Run deficits. Cancel a jet-fighter buy. End first-past-the-post elections. Implement every call to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Legalize pot. Skip the entire first day of the campaign so he could keep a promise to march in the Vancouver Pride parade. His older opponents were left sputtering. The papers were full of premature autopsies:

He won. Then he won twice more, though on a perceptibly downward trajectory of support. Of course a few of his glib promises burned him later — fighters, electoral systems, jets, reconciliation to some extent. Most of us get risk-averse as we age. It’s natural for challengers to claim everything’s broken, just as it’s natural for incumbents to insist everything’s fine.

But there’s a difference between mellowing with age and digging yourself a rut as deep as the Saguenay Fjord. Everybody knows Trudeau’s playbook by now. There’s trouble? Dispute the news accounts. Stall. Get Chrystia Freeland to say she has full confidence in the boss. Appoint some gimmicky cabinet committee that promptly vanishes. When a parliamentary committee investigates, work it so senior staff members don’t testify. Say you’ll be “there for” somebody.

What would he do if he were still capable of surprise? Maybe something like this.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paul Wells to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.