Please state the nature of the emergency

MPs and senators ask which unprecedented facts required an Emergencies Act

In any self-respecting three-ring circus, the action is always at different stages in each ring. Equipment is being rolled into one ring and carried out of another, while the elephant dances a tarantella in a third. The Trudeau government’s February invocation of the Emergencies Act — the first use of the Act since it became law in 1988 — to clear trucks, revellers and hot tubs away from Parliament Hill is now being tested in three rings: the law courts, a public inquiry, and Room 025-B of Parliament’s West Block, where the Special Joint Committee on the Declaration of Emergency heard its first witnesses on Tuesday.

Rhéal Fortin, the Bloc Québécois MP for Laval-des-Rapides, is the committee’s chair. He is also its only Bloc member, so he would periodically hand off his presiding responsibilities to another MP so he could spend a few minutes grilling a cabinet minister.

Fortin is preoccupied with Section 25 of the Emergencies Act, which says every province’s government “shall be consulted” before its invocation. There is no suspense here: the requirement is only that they be consulted, not that they agree to anything. But wow, not a lot of provinces agreed.

“The premier of Quebec opposed the application of the Emergencies Act, and even said it would be a source of division,” Fortin told Justice Minister David Lametti, who knows this. Alberta’s and Saskatchewan’s and Manitoba’s premiers were opposed. In New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, the premiers said the law wasn’t needed. That left three provinces — British Columbia, Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador — whose governments thought it would be a good idea to invoke the Act. Obviously Ontario’s support is important here. Fortin was preoccupied with all the opposition.

“What use are the consultations?” Fortin asked.

Lametti replied what Fortin knew: that unanimity or even majority approval isn’t needed, only consultation.

“But what use is it?” Fortin said.

“Well, consultation is always useful,” Lametti said.

“Yes, but what use is it?”

“To take the temperature in the room.”

“Why?”

“It’s very important.”

“Why?”

“To survey what the premiers think.”

“Why, if you don’t take it into account?”

Here we should perhaps back away from the dancing elephant and consider the bigger picture. But yeah, it was that kind of day.

A trend is emerging as the three venues for review of the Emergencies Act’s first use grind, at varying speeds, into gear. The Trudeau government is trying to obscure the central question, which is, why were this act’s extraordinary powers needed, for the first time in its 34-year existence?

In court, the Crown is arguing that cabinet confidentiality keeps it from revealing all of the evidence it had for making its decision. As a bonus, it’s arguing mootness — there’s no point arguing about this now, because the Act’s measures were allowed to lapse after 10 days — and standing — that the litigants haven’t a direct enough interest to make a case.

In the public inquiry, which the government convened on the last possible day required by law, the terms of reference have raised eyebrows because the feds invite Justice Paul Rouleau to investigate every aspect of the truckers’ behaviour while showing little curiosity about the feds’ behaviour. (In fact, the best advice I could get when I called lawyers on Wednesday is that the Act itself is so clear that no terms-of-reference smoke-screen can have much effect. It requires any inquiry to examine both “the circumstances” and “the measures taken.")

And in opening-day testimony before the joint Parliamentary committee, Lametti and his colleague, Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino, were heavy on the atmospherics and light on the details. February’s string of traffic-blocking protest mobs in Ottawa and a string of border crossings was terrible, they said, so they did the right thing and then everything was fine. How things got to be so terrible they decided to dust off an ancient law, and which specific triggers led to their decision, they wouldn’t say.

Mendicino, who was tenacious but courteous to colleagues in both official languages, said “a series of unprecedented and simultaneous public-order emergencies across the country” had included, “by any sensible definition… a massive illegal occupation in Ottawa for nearly a month.” Life in the capital was “unbearable and unsafe” and the economic impacts “were devastating.” At Windsor alone the lost cross-border trade was $390 million per day, he said. (Conservative MPs pressed Mendicino on fresh reporting based on Statistics Canada data that suggests the cost was nowhere near as high, because two countries’ predominantly non-protesting truck traffic simply avoided Windsor. Mendicino stuck to his story.)

Mendicino quoted Pat King, a prominent organizer of the February convoy and all-around piece of work, who said in a December Facebook Live video that COVID-related restrictions and mandates had gotten so out of hand that “the only way that this is going to be solved is with bullets.” He cited the “Memorandum of Understanding” which some convoy organizers posted until they un-posted it, calling on Senators and the Governor General to collaborate with the convoy protesters in setting up a provisional junta to replace the Trudeau government. This is an actual thing that happened.

I hope any government of Canada would take this sort of talk seriously and that its authors would run into legal trouble. King and several other ringleaders sure have. Tuesday’s committee session offered a glimpse into the environment within with the Trudeau cabinet made its decision. David Vigneault, the director of CSIS, told MPs and senators that “ideologically motivated violent extremism” will soon take up half of his agency’s investigative capacity, against “religiously motivated violent extremism” whose once-overwhelming share of CSIS’s attention is shrinking. You can absolutely bet that the worst of what CSIS finds or suspects is winding up, at regular intervals, on the desks of Justin Trudeau, his senior ministers and advisors.

Nor is CSIS chasing fantasies. Corey Hurren drove a truck full of firearms onto the prime minister’s lawn in 2020, in what a judge called “a politically motivated armed assault.”

But notice how, even here, I’m indulging in mission creep that seems to resemble the ministers’ when they testified. The question at hand is not whether bad people are at large or bad things happen. Of course they are and do. The question is whether February’s bad things were the first since 1988, really the first since 1970 while we’re on it, to require a sweeping extension of police powers. As I wrote for a magazine on the night the Emergencies Act’s invocation was announced:

Five prime ministers have had the Emergencies Act and declined to use it. Brian Mulroney didn’t use it during the two-month Oka standoff outside Montreal in 1990. Jean Chrétien didn’t need it after 9/11, Stephen Harper didn’t need it during the 2008 banking crisis. And Justin Trudeau didn’t use it during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw 35,000 deaths and the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression. What’s different about today?

Mendicino’s prepared remarks were, on this point, actually not much different from mine. “Such authority should be granted only when it is absolutely necessary and strictly for the purposes of addressing a specific state of emergency,” he said. He urged parliamentarians to investigate “not just what happened but how to ensure that it does not happen again.”

To his chagrin they did. Conservative Senator Claude Carignan, a lawyer and former mayor of St.-Eustache, was hilarious on this front. “I’m trying to understand why you used the Emergencies Act,” he told Mendicino. “There’s absolutely nothing that you did with the Emergencies Act that you couldn’t have done without it.”

Mendicino replied that the trucks wouldn’t move and the municipal tow-truck force wouldn’t tow them. “Mr. Minister, I found some on Auto Hebdo!” Carignan interjected. He was referring to tow trucks. “You could have bought them and towed them yourself!”

Larry Campbell, a former Vancouver mayor who belongs to one or the other of the not-quite-Liberal Senate factions I find impossible to track, wondered why, if the danger from the convoy was so grave, the buildings in the Parliamentary precinct weren’t closed to parliamentarians and government staffers until quite late in the drama.

Soon after, Lametti was so eager to remind everyone of his free-speech credentials that he said, triumphantly, that after the Emergencies Act made tow trucks work again and Wellington Street was cleared, “the protesters set up legally on sidewalks further down the street and nobody bothered them. And they were allowed to make their point.” Which comes closer to proving Campbell’s point than Lametti’s, I thought.

I asked a few smart people to rank the three Emergencies Act challenges by importance. Everyone agreed it’ll be easier to answer that question at the end of the processes than at the beginning. But the court challenges will have to fight, at a few steps along the way, even to be heard by a judge. The parliamentarians have an impressive witness list — Chrystia Freeland and Ottawa mayor Jim Watson may yet appear — but the committee’s demands for documents will mostly be easy for the government to ignore. The public inquiry is likeliest to pry records and testimony out of a reluctant government. So it’s Justice Rouleau’s report, next February if he can meet his ambitious deadline, that will feel most like a climax to this odd chapter. I’ll check in from time to time as all three challenges progress.

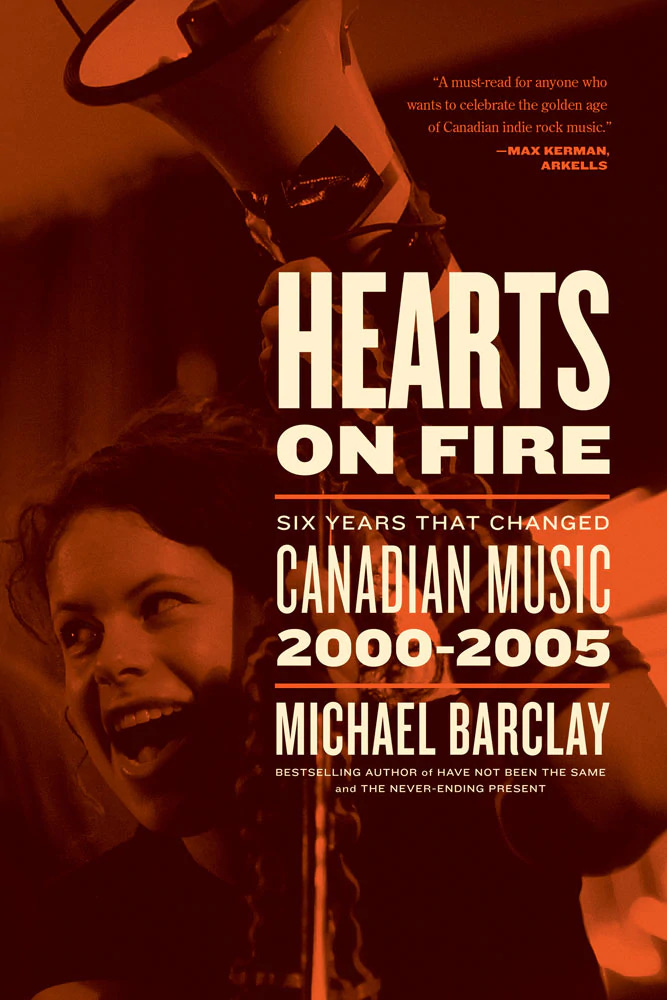

Now you’re outside me, you see all the beauty

This week marked the release of Michael Barclay’s epic 600-page history of Canadian alternative rock at the turn of the millennium, Hearts on Fire: Six Years That Changed Canadian Music, 2000-2005. Michael is a friend. We used to work together at a magazine and there’s a blurb from me on the paperback cover of his astonishing history of Gord Downie and the Tragically Hip, The Never-Ending Present. If you’re between your mid-30s and your late 40s and you spent too many nights two decades ago holding your hopes up to the light of Arcade Fire, Stars, Feist, Hawksley Workman, Joel Plaskett and Alexisonfire and their peers, Hearts on Fire is for you. I’m aged out and I was mostly listening to jazz, but I kind of get it. Barclay is a real reporter, a social historian, a friend to many of these bands, and he explains the social and technological changes (Pro Tools; tour subsidies; cheap-ass rent in post-referendum Montreal) that made it feasible for a generation of artists to reach the world from Canada. Each of his books takes a part of our history seriously that you didn’t even realized you were allowed to take seriously. I couldn’t be happier to commend Hearts on Fire to your attention.

Good morning, When listing Prime Ministers who did not invoke the Emergencies Act, you neglected to mention that the Act was not invoked by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau back in February, 2020 when Indigenous protesters blockaded Canada's railway tracks for weeks, and also blocked various ports across the country. How quickly we forget. What is also interesting is that Marc Millar was sent to negotiate with the Indigenous protesters, while the Freedom Convoy protesters were completely ignored.

Paul,

You said: "…calling on Senators and the Governor General to collaborate with the convoy protesters in setting up a provisional junta to replace the Trudeau government. This is an actual thing that happened."

Citation please??

I found the text here: https://www.netnewsledger.com/2022/02/05/the-canada-unity-memorandum-of-understanding/. Please point precisely to where the MOU says such things??

First, let me say, I think writing the MOU was a dumb thing to do. I think it was motivated more by desperation than malice. But what I see in that document is:

- A request to the Governor General, the Senate, and the MPs to form a COMMITTEE called "Citizens of Canada" and appoint members to it.

- Then those entities indicate specific dates for the desistence of each of the mandates. ("immediately" is the request, but note that sections e, f, g, and h have unique dates).

On a related note: do you think it's possible the laymen who wrote this MOU document were inspired, perchance, by the events in Smithers, BC, on February 27, 2020 wherein a COMMITTEE was struck to negotiate the desistence of Rail Blockades?? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Canadian_pipeline_and_railway_protests#Meetings_and_memorandum_of_understanding

Get past the faulty legalise and notice the document is essentially a request to get relevant people in a room to describe a plan - a timeline - for ending the mandates.

And remember: ALL opposition parties were, contemporaneously, calling on the Liberal Party to announce a plan - a timeline - to repeal all the mandates.

Paul, I sense you've gotten used to spinning this issue like a top. But you can now choose truth.

Please choose truth.