It is normal to wonder how a creator creates. Whether you’re at a magic show trying to figure out how the coin escaped the magician’s hand, or you’re in a theatre wondering how a bunch of people managed to enact a story you’ll never forget, there’s a mystery at the heart of the creative moment. That’s our topic for the podcast this week.

Our guide is Adam Moss. He is perhaps new to you. But I come from magazines, so let me tell you about Adam Moss.

The Americans have an actual Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame. In a genius move, they don’t add to it every year — because realistically, how often does a hall-of-fame magazine editor come along? But Adam Moss is in it. That’s because from 2004 to 2019 he edited New York magazine. And even though city magazines are a tightly constrained form — it’s mostly service journalism; you need to tell residents where to shop and visitors what to see, and only after you’ve nailed that stuff down do you get to tell a few honest-to-God stories about the place — Adam Moss reinvented New York, made it relevant and appealing, guided it gently into its digital future. His trademark was the back-page Approval Matrix, which maps the week’s cultural events across four quadrants: Highbrow, Lowbrow, Brilliant, Despicable. But his contribution goes way beyond a funky page. New York won six National Magazine Awards for General Excellence and four for Design while he was its editor.

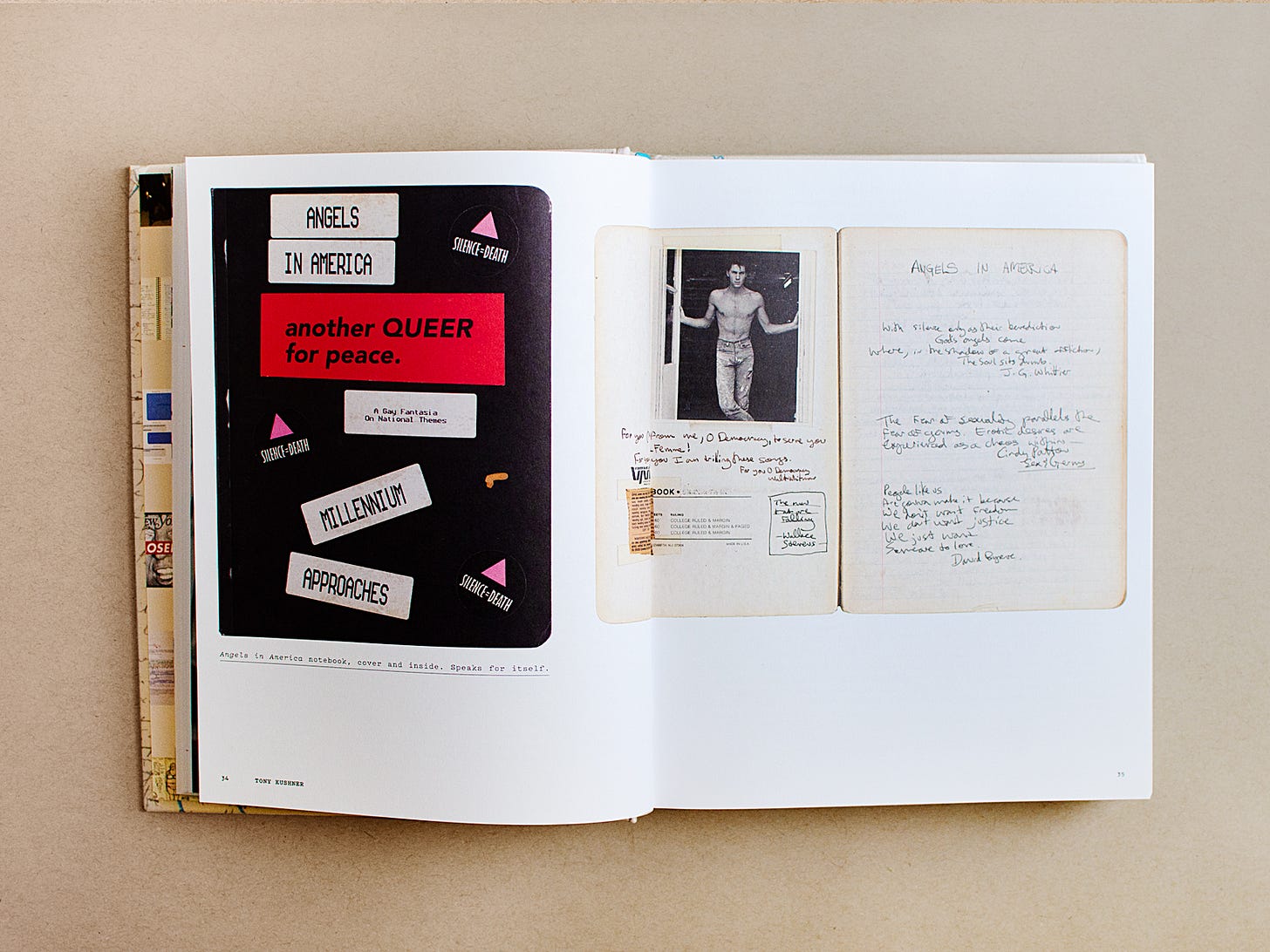

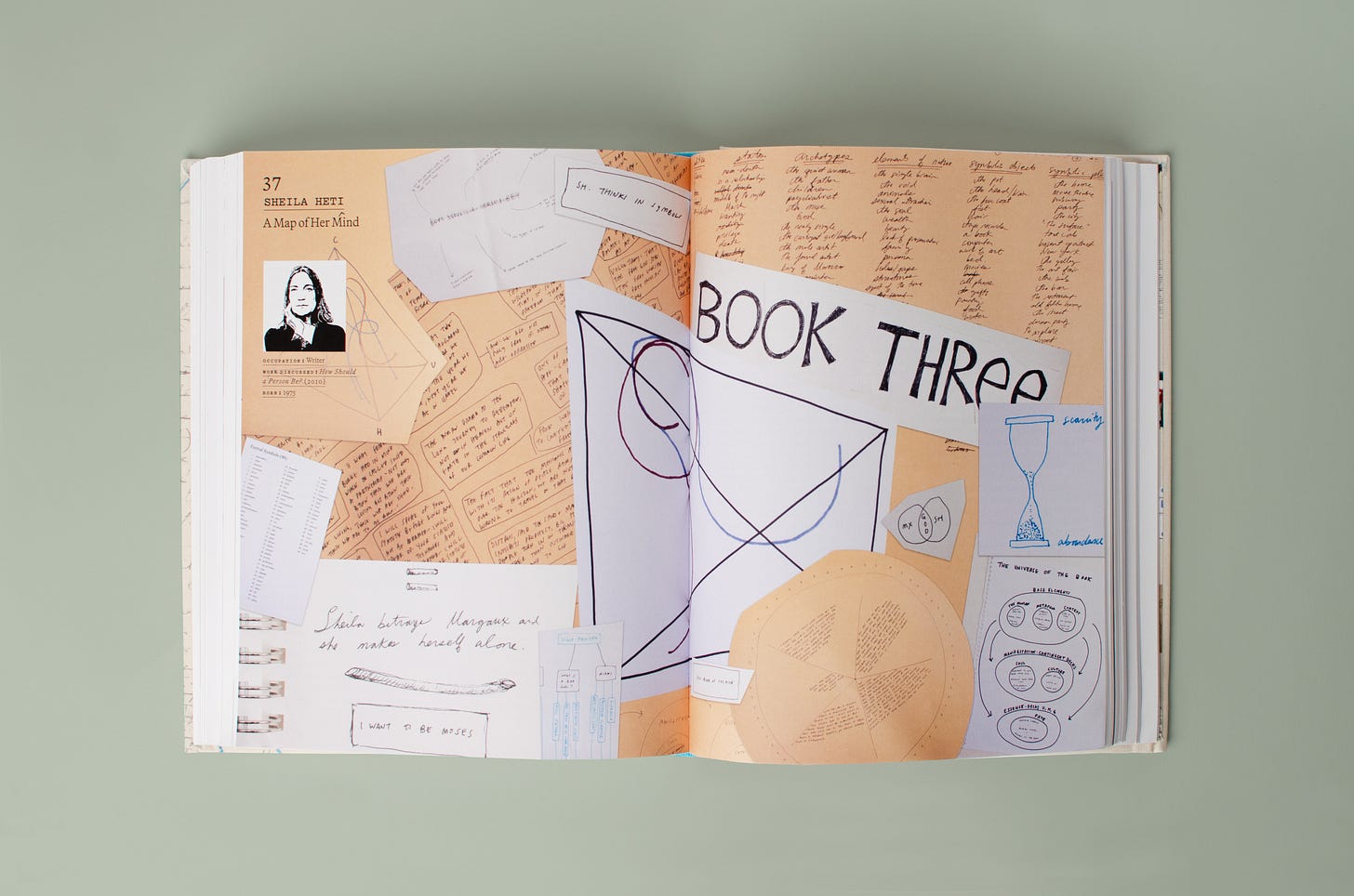

He retired not long before COVID broke out all over, and now he’s come out the other side with a book. It’s called The Work of Art. It’s concerned with that irreducibly mysterious question: Where does art come from? Moss interviews 43 creators — from legends like Stephen Sondheim and the playwright Tony Kushner to architects, poets, painters, composers, sand-castle sculptors and the showrunner for Veep — about how they made specific works.

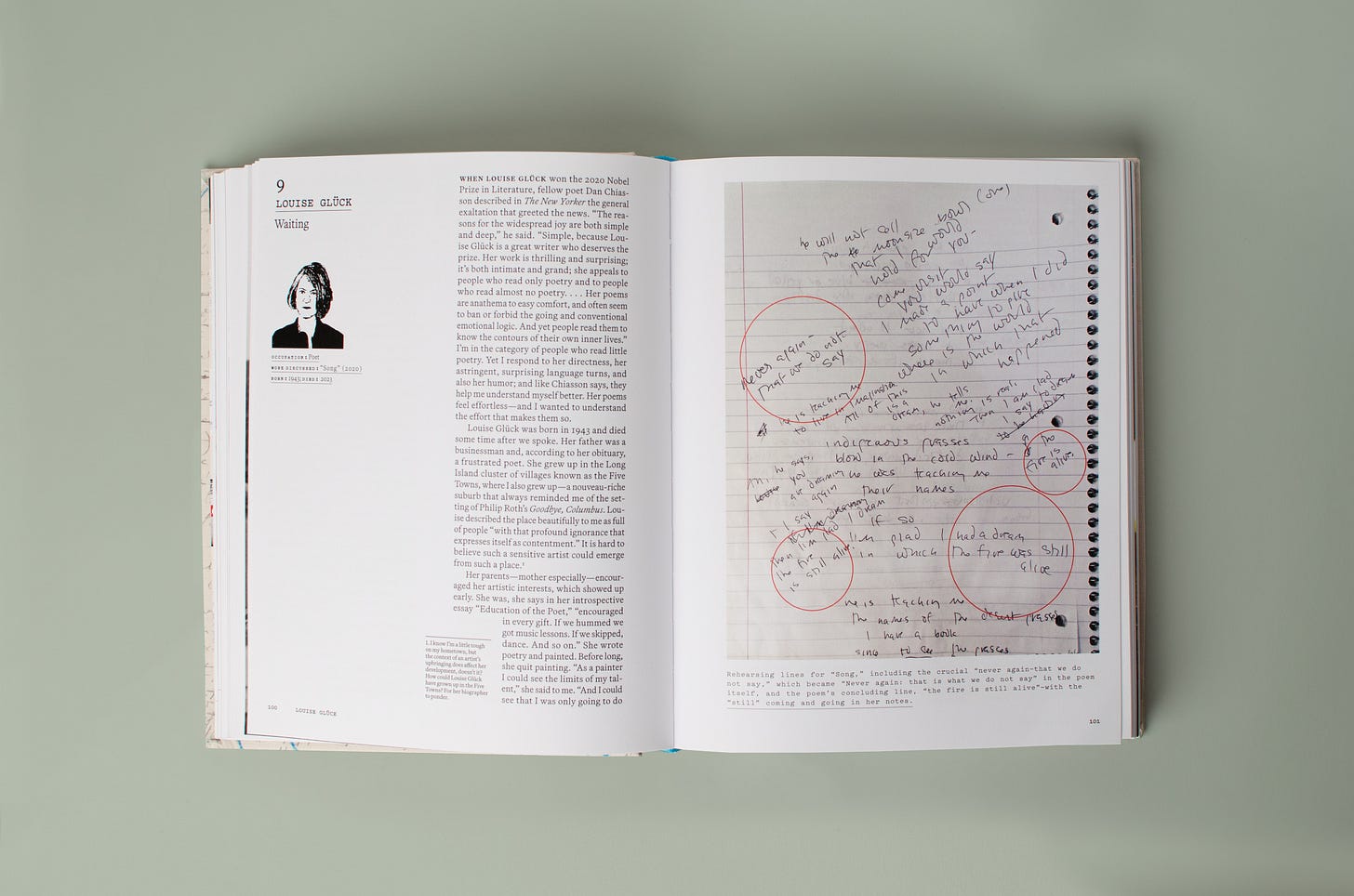

But he didn’t just interview them. He asked each one to show their work: early sketches, rough drafts, rejected efforts, diaries, text-message logs, the “creative entrails” of the process. So you find yourself going through each artist’s work week, while the artist discusses the stress, epiphanies and trade-offs of creation, and Moss stands at their elbow, refusing to let them off the hook. Here are spreads from the book’s chapters on a poem by Louise Glück, Kushner’s epic two-play cycle Angels in America, and Sheila Heti’s novel How Should a Person Be?

Across all these dozens of cases, Moss finds common themes. The need for secrecy around a project in its early stages (novelist Michael Cunningham: “There’s no surer way that I know to lose faith than by summing it up too soon. ‘It’s about a guy, a whale bit off his leg, he’s really mad.’”) The near-certainty that your original plan won’t survive. (Cunningham again: “It took me a while to realize that if a novel is any good, it’s going to defeat what little idea that took you into it in the first place. It’s going to become something else, and your experience of that as a writer is, Oh it’s just not working out.”) The self-loathing that ensues. (Sofia Coppola: “Everyone feels like their stuff is awful.”) The utility of assets that don’t feel creative at all: a deadline, a dare, technique and muscle memory built up from a lifetime of making things.

It’s surprising how often people talk about their work as an objective thing outside them, whose form emerges through conversation. Well, the poem told me it wanted to go in this direction. Or I tried this, but the painting didn’t like that. Or rather, it’s surprising at first, and then it becomes a recurring theme.

We get into all of this in this episode. Moss didn’t know me from Adam, so to speak, but I think I felt him warming to the conversation as we went along. Which was good, because I also wanted to ask him about his own creative process.

As with the creators he interviews, I had a specific work in mind.

September 11, 2001 was a bright sunny Tuesday in New York City, and at that point in his career Moss was still the editor of the New York Times Magazine, a weekly insert with its own pedigree. Inserts are freeing in a lot of ways, because you don’t need to use the cover illustration to persuade people to buy them. You can be quirky, because the damned thing is going to flop out of the newspaper onto the floor no matter what’s in it. Whatever was going to be in the Times Magazine on Sept. 22, 2001 was nearly done by the 11th, because the Times Magazine closes on a Friday nine days before it hits newsstands.

And then, on this particular Tuesday, airplanes started flying into buildings.

Whatever was going to be in the Times Magazine went away. Moss and his colleagues had about 48 hours, under tremendous logistical strain, to come up with something new. The particular challenge they faced is almost impossible for the rest of us to remember or imagine, this long after the fact: they had to throw an entire issue of the magazine forward a week and a half, at a time when nobody could imagine what the world would look like that far in the future.

What they came up with was an issue I kept for years and have read dozens of times:

It’s mostly short essays by the magazine’s contributing writers at the time, including Andrew Sullivan, Colson Whitehead, Richard Ford, Margaret Talbot. The issue’s success is down to many of the the elements Moss describes in his book: a deadline, a dare, having to throw out your plan, wondering whether you’re good enough. Moss and I discussed all of that, too.

We’ll get back to newsmakers and Canadian politicians soon on the podcast, but I am as pleased with this episode as with anything else I’ve done since I launched this newsletter. Trust me on this one.

You can listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts and a bunch of other platforms via the “Listen On” button that you can see at the top of this post when you view it on your desktop. You can download any episode to listen to it later, via the same “Listen On” button. If you listen on a podcast platform, smash those “Like” and “Subscribe” buttons, and leave a good review, to help spread the word.

You can read a (machine-generated) transcript of this week’s episode via the "Transcript” button at the top of this page when you view it on your desktop browser. I’ve had epic battles with the transcription software this week, but reading the result, I’m pretty sure the AI is getting smarter.

I am grateful to be the journalist fellow-in-residence at the Munk School at the University of Toronto, the principal patron of this podcast. Antica Productions turns these interviews into a podcast every week. Thanks to all of them and to you. Please tell your friends to subscribe to The Paul Wells Show on their favourite podcast app, or here on the newsletter.

Share this post