“There is also the Warren Report, of course, with its twenty-six accompanying volumes of testimony and exhibits, its millions of words. Branch thinks this is the megaton novel James Joyce would have written if he’d moved to Iowa City and lived to be a hundred.” — Don DeLillo, Libra

Any large enough thing permits multiple uses, including uses nobody could have predicted. My sainted policy prof at the University of Western Ontario, the late Robert A. Young, used to say the best public-administration textbook you could find was a Government of Canada telephone directory. You could measure how important some function of government was by counting how many pages of phone numbers were associated with it. Not a lot of room for understatement or exaggeration. And in those days, if you had a question about some office you could call the person in it. They would answer and talk.

What is happening at the Library and Archives of Canada on Wellington Street, a few blocks past the improvised but seemingly permanent traffic barriers that stayed in place after February’s unpleasantness ended, isn’t designed to provide us with an education in how we are governed, but it just can’t help itself.

The Public Order Emergency Commission under Justice Paul Rouleau is hearing witnesses at an accelerated clip. Rouleau is squeezed. He must report by Feb. 20, but the start of public hearings was delayed by nearly a month because he needed surgery. Days at the commission are long, breaks short.

Most days this week there have been about 15 reporters in the media room across the hall from the commission hearing room. We are welcome in the commission room with Rouleau, the witnesses, two rows of lawyers for interested parties, and a couple of dozen spectators. There are seats but no tables for reporters to rest their laptops, so it’s just easier to set up shop in the media room. There’s wi-fi and the reporters from the National Post usually bring snacks. We get the same live video feed everyone in the world can get, plus, after a couple of days’ initial delay, quick access to electronic copies of the documents witnesses discuss in their testimony. In front of the building, a man carrying a maple-leaf flag and wearing an actual tinfoil hat stands guard each day until mid-morning.

This post is long and, especially near the end, handles thorny questions. I’m making it available to everyone, not just paying subscribers. If you think this piece is interesting, tell a friend — using the button below or, even better, by just emailing this article to them or telling them you like the work I do here.

I like free subscribers, which is why much of my work here will always be free. If you want to support my work and have access to the stuff behind the paywall, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The big news organizations are working in teams of two, taking turns live-tweeting and spelling each other off in improvised writing shifts, because the hearings are such a firehose of information it is risky to look away. The server for Thursday’s session alone contains 24 documents, from single-page memos to 247 pages of handwritten notes somebody scrawled while former Ottawa Police Service Chief Peter Sloly went about his days. And 141 pages of notes his acting deputy chief, Patricia Ferguson, took in her own neater hand during roughly the same period.

There are redactions — blacked-out spaces where some government authority decided something couldn’t be made public under an assortment of standardized exceptions — but actually not a lot of them. What gets through is amazing enough. Figure 500 pages of text per day, plus 10 hours of oral testimony, usually two witnesses guided by commission counsel and then tested or challenged by lawyers for Sloly, the police union, the convoy participants, the benighted residents of Centretown or some other interest.

The goal of it all is to permit Rouleau to decide whether the Emergencies Act was used properly when it was invoked, for the first time in its 34-year existence, by the Trudeau government to end the mess in Ottawa’s Centretown. But it’s also a deep dive into conflicting ideas of police doctrine, the best look we’ve had at the stressed and dysfunctional city administration in Ottawa. And while we haven’t yet heard much about the Trudeau government’s processes, that’s coming. The prime minister and seven of his senior cabinet ministers, with their deputies, will testify soon.

Nobody can keep up with it. For Ottawa reporters it’s as though we’ve dragged ourselves for a decade through a desert of talking points and euphemisms into an oasis of unbelievable information bounty. The temptation is to gorge. I took Wednesday off, only to learn that Diane Deans, the city councillor who was heading the Ottawa Police Service Board when the mess began, secretly recorded the call in which she informed Mayor Jim Watson that she’d gone ahead and negotiated the hiring of an interim police chief Watson had never heard of. Here’s the recording:

Aaron Sorkin couldn’t have written it better. Deans tells Watson she’s found a new police chief for him in the middle of the worst public-security crises of their lives. He tells her it’s a terrible plan. She asks whether he’ll vote to remove her from her post and he won’t say, which of course is the same as saying. They talk about what to do next, in a way that leaves room for each to have an understanding of what they agreed that’s incompatible with the other’s. It’s gold. The consensus on Thursday among Parliament Hill people I talked to who’d heard the tape was that conversations like this happen all the time in workplaces across the capital, as of course they happen around the world. It’s just that usually in governments, as in most large organizations, any sign of their existence is buried under lakes of Novocaine.

It’s starting to be noteworthy how often people in government record their important conversations. Almost as though people were increasingly worried they might be lied about. When Jody Wilson-Raybould did such a thing three years ago, it was possible for her ex-colleagues to clutch their pearls and protest that such a thing just isn’t done. But after months of claims and assertions about what RCMP commissioner Brenda Lucki told the RCMP detachment in Nova Scotia, nine days after the worst mass murder in Canadian history, it’s handy to have a recording, isn’t it.

By this emerging standard, Patricia Ferguson is old-fashioned. As far as we know she didn’t record her meetings. But she did break open a notebook methodically, like clockwork, to write detailed longhand notes after her conversations. Those notes are hard to reconcile with the portrait Deans painted in her testimony a day earlier, of Peter Sloly as a lone good man, standing up for proper policing in the face of heckling and even racism from the city’s old guard.

In Ferguson’s version, it sounds like Ottawa’s cops were all reasonably good but they were cracking and colliding under immense pressure.

Ferguson described an Ottawa Police Service already worn down by the beginning of this year. There had been retirements, resignations, a high-level suspension and a suicide before and during the COVID lockdowns, followed by Black Lives Matter protests with the attendant internal soul-searching and external scrutiny every North American police corps faced.

And then the convoy hit. And then it stayed. This last was more of a surprise than it should have been.

The late stories out of Wednesday’s testimony were from Pat Morris, an Ontario Provincial Police superintendent in charge of intelligence-gathering. He dumped a bunch of old OPP “Project Hendon” reports, a term of art for the force’s intelligence-gathering operations, onto the commission server. Those reports were sent regularly to the Ottawa police as the various truck convoys approached the capital. Ferguson testified that she didn’t become aware of them until just before the trucks arrived. Which is too bad. What the OPP had found was a very large group of protesters from all over. They did not pose an organized threat of violence, though the Hendon reports acknowledged that confrontation can always escalate and that “lone wolf” extremists could well be tempted to join the crowd. But all the trucks represented a huge problem anyway, because they had rapidly growing funding — and no plans to go home at any point.

If weekends end on a Sunday, almost all the trucks should have been going home on Jan. 30. They didn’t. This quickly became disconcerting. On Tuesday, Feb. 1, Stoly wrote a note to himself summarizing a meeting he’d just left — it’s Ottawa, everyone does it — in which he had berated Staff Sgt. Michael Stoll for not having a plan in place to make the protesters leave town.

What struck Frank Au, a member of the Rouleau commission’s legal team, was that the commander of the police force was telling a junior officer what to do. This was also noteworthy to Trish Ferguson, who would have been in the chain of command between Sloly and Stoll if the Ottawa Police Service still had a functioning chain of command. “Yeah, he was directing a staff sergeant,” she said wearily. “We did speak to him about not directing a police operation.”

As the situation deteriorated, Sloly started clenching up big time. He wanted massive reinforcements and strong action against the protesters. The convoy was burning out Event Commanders — senior officers responsible for directing the OPS response to the convoy — at an alarming rate. One stepped down on Feb. 4 from exhaustion. The next lasted two days until Ferguson realized Sloly didn’t trust the new guy, so he stepped aside too. The third, Superintendent Mark Patterson, came in on Feb. 10.

Sloly was out of patience with the protesters. Patterson was his enforcer. Ferguson was a huge advocate of using the OPS’s Police Liaison Team to get to know protesters, listen to their demands, and “give them wins.” Patterson thought this was all bollocks. At one point the protesters offered to move some trucks in exchange for port-a-potties inside the so-called “red zone” around Parliament Hill. “The response from the Event Commander was, ‘We’re not gonna give them one inch,’” Ferguson recalled mournfully.

Sloly was out of inches too. He announced a new operational plan, whose plan was to “cut off and cauterize the heads” of the “hydra” the convoy represented.

Cauterize? “It was not a term I’ve heard used in event planning before,” Ferguson told Au drily. Reading from her notes, she said Sloly had told the OPS senior command: “Anyone who undermines the operational plan, he would ‘crush’ them. He said this twice.” His jaw was clenched and twitching as he spoke, she noted.

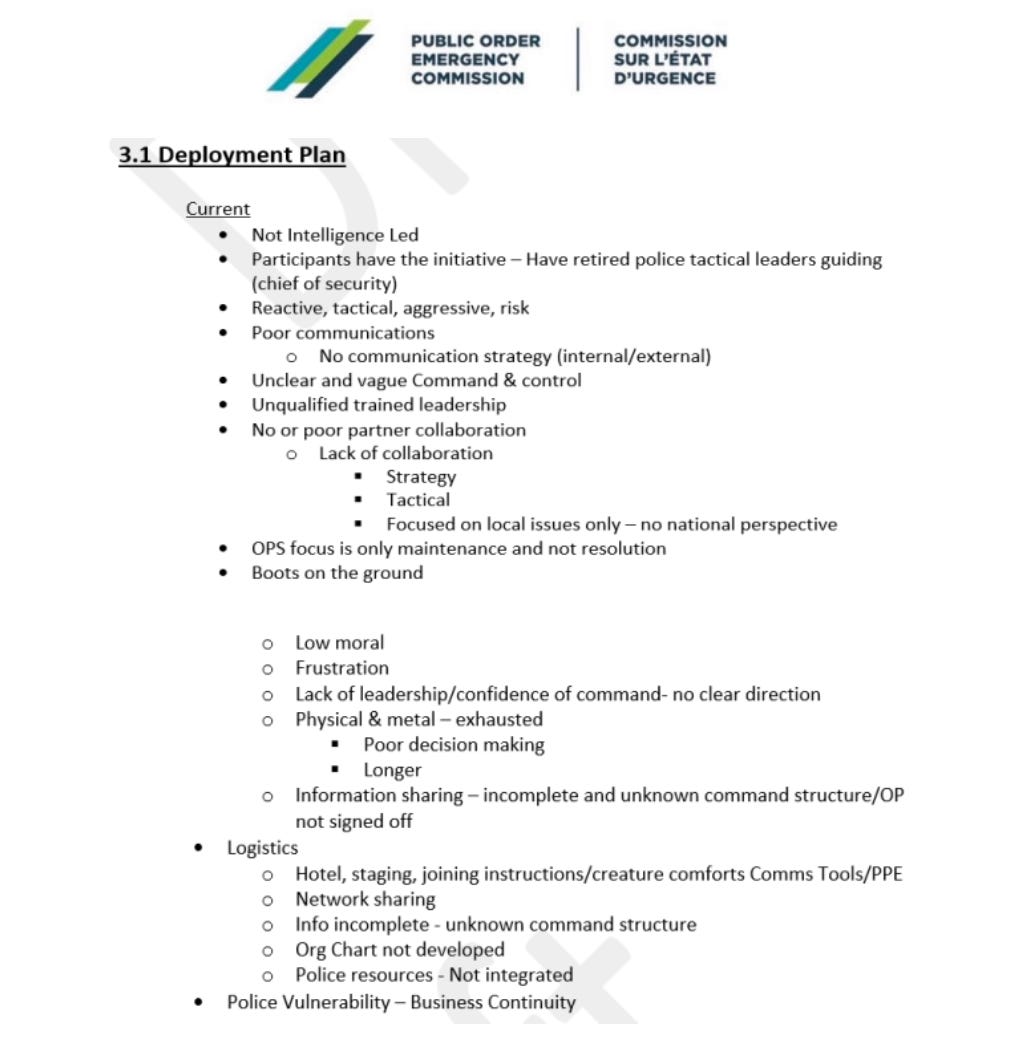

Sloly himself will testify later, of course, and we’ll let him give his version then. For now, as a measure of the extent to which the crisis had degraded the OPS’s internal cohesion, it’s probably best to note how their colleagues saw them. By Feb. 10, the OPP was in town and was working with the RCMP in an Integrated Planning Team. They came up with a draft plan to bring the mess to an end, and part of the plan involved a read on the police response so far — that is, the Ottawa police response. Here’s the OPP/RCMP read on the OPS:

It’s not great. Cleaning up spelling and grammar a bit, it says the Ottawa police response was “not intelligence-led.” The protesters had an edge because they had retired police officers planning their actions, as was widely reported at the time. OPS actions were “reactive, tactical, aggressive” and thus escalated the situation’s “risk.” There was “low morale.” And so on.

As Frank Au, the commission counsel, read this evaluation to Ferguson, she said she had to agree with just about all of it. Feb. 10 was the day she went home for two days after a confrontation with Patterson. She told Au it was the worst day of her career. As it turned out, it was also Patterson’s last day as Event Commander. When Ferguson returned to work two days later, everyone was working better together. But that’s a story for another day.

What I want to concentrate on instead is the core of the dispute between Ferguson and the OPP on one side, and Sloly and Patterson on the other — between conciliators and enforcers, if you like.

During the siege of Ottawa, which seemed to last a lot longer than three weeks while it was happening, it was common for observers to describe scenes in which police officers ignored provocative or loutish behaviour, or worse, from protesters. Ferguson’s testimony suggests this really happened; that it was by design; that to her mind it was useful; and that at any rate it represents recent evolutions in police doctrine for dealing with large demonstrations, not only in Ottawa but across Canada and, indeed, abroad.

Trish Ferguson was just about the OPS’s biggest fan of the force’s Police Liaison Team (PLT). “It really is an amazing tool,” she told Au. It permits “longer-term wins” for the police and the protesters. (The notion of protesters getting any kind of win will be shocking to many readers. Honey, I’m just getting warmed up.) “People walk away safely, they feel that they were heard and their objectives were met.”

What’s a PLT? In a summary of a preliminary interview that Ferguson gave the commission this summer, they’re described as:

“…police’s first point of contact with protestors and as a great way to get information on protests and ensure public and officer safety during protests. PLT engages with protestors to facilitate lawful protest, learn about their intentions, and warn about lines that protesters cannot cross. If disruptive behaviour occurs during an event, PLT will engage with protestor contacts to attempt to de-escalate the situation.”

There are about two dozen PLT officers in the OPS, the pre-interview document says. It’s part-time work in addition to other tasks. Perhaps a dozen worked during the convoy, reporting to Ferguson. They’d been trained in how to do the liaison work in fall 2021. She “encouraged that training because PLT members had reported to her that, during a past event, they felt they were not performing as they should under the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police National Framework for Police Preparedness for Demonstrations and Assemblies.”

There was some back-and-forth between Au and Ferguson about all this during Thursday’s testimony. She said the OPP had their own liaison team, and were well used to its principles after long work with protests, “including Indigenous protests.” So she saw eye to eye with the OPP and the RCMP. Sloly and Patterson, on the other hand, were strongly opposed to “negotiating with unlawful protests,” as Ferguson recalled.

Ferguson’s argument was, in effect, well, what’s an unlawful protest? “Crowds, 80% of them are law-abiding,” she told Au. “If you give them a win they will go away peacefully.”

After a while I thought I should see what the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police has to say about all this. You can find its National Framework for Police Preparedness for Demonstrations and Assemblies here. It was published in 2019. I should emphasize that it’s a “suggested best practices” document: it’s advice, not rules, and any police force is free to take it or leave it. But it’s deeply imbued with the spirit Ferguson described: its goal is to facilitate lawful protest and to de-escalate, rather than simply sanction, disruptive behaviour.

From the Framework:

“The Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP), Policing with Indigenous Peoples (PWIP) Committee was formed to consider matters relating to sustainable policing services and enhanced public safety for Indigenous peoples and communities throughout Canada… This best practices document is intended to address any and all issue-based conflicts and is not limited to those impacting Indigenous peoples or communities.”

So: Indigenous in inspiration and development; applicable to non-Indigenous assemblies as well. I am keenly aware that there is plenty of material here for dispute. But let’s keep reading for a bit.

The document lays out a few “foundational principles” that should guide any police response to any large demonstration. They include a “measured approach” that “emphasizes… proactive engagement, communication, mitigation and facilitation” in interactions with protesters; “relationship building” to enhance “trust;” an approach that “facilitat[es] lawful, peaceful and safe demonstrations;” and “impartiality,” which includes treating governments “as any other stakeholder. Police are independent and should not take direction from any level of government in relation to response to demonstrations and assemblies.”

In applying these principles, “the development of specific Liaison Teams,” like the PLT that reported to Trish Ferguson, is “strongly recommended.” The duty of Liaison Teams “is to liaise not enforce… The primary role of a Liaison Team is to build and foster relationships.”

There is more, 28 pages in total, but I’m already trying your patience today. Perhaps I’ll leave the Framework with you to read, if you like, adding only that in a list of things to look for after an event has ended, the document includes, in a masterwork of understatement, “Differing perceptions of the issue or event by those involved.” That’s all of us. Canadians. I think it’s fair to say we’ve delivered on our end of the bargain.

Let me anticipate a few objections. First, despite energetic revisionism by some of their admirers, the convoy protesters were not choirs of angels. Police laid hundreds of charges, including a smaller subset of charges for assault and weapons offences, during or after the convoy. Every elected official who’s testified so far has said they received death threats.

In a complex world, many things can be true at once: that crime went up when the circus came to town, and that many of the protesters were, to varying degrees, peaceful. I can’t help noticing that the comment boards here at Paul Wells are full of people trying to win arguments, usually with admirable civility. I’m not here to win arguments, so I get to notice that the convoy was a complex event. Here’s the thing: the Chiefs of Police’s best advice is that most of the time during a complex event, cops should not be in the business of wading through crowds assaying virtue. Their goal is to let the protest happen and end.

Second, a normal expectation of these events is that the protests will arise among long-term inhabitants of a local area — that people normally get angry, and organized, where they live. By that light, the convoy will look to a lot of people like an invasion, to be judged and handled by different rules. I’m not sure I buy it. How many of those trucks were from within 100km of Parliament Hill? Or 300? And how many protests you’ve supported involved people who arrived from across the country, or from Sweden?

And once again: Should police be in the business of drawing such distinctions on the fly, using their own judgment or following governments’ orders?

Finally, the obvious biggest potential challenge to all this: that it’s lurid and even racist to apply, to a non-Indigenous protest, rules that were drawn up, woefully late and after episodes of ghastly brutality, for Indigenous protests. I have no reply that will change minds on this. The Chiefs of Police, though, seem pretty sure they’re describing appropriate responses to any large demonstration. They repeat that point several times.

I have some history with this. In June here I wrote about two fascinating polls Greg Lyle at Innovative Research Group had conducted in 2020, during the Wet’suwet’en-led blockade of rail lines to protest against the Coastal GasLink pipeline project, and in 2022, during the convoy. Each time, Lyle asked respondents: Do you agree or disagree that if governments met the protesters, it would encourage more such disruptive tactics? Answers to the two questions tended to be very different, and they tracked partisan political preference closely. It’s very difficult for a lot of people to imagine the rail blockade of 2020 and the convoy of 2022 might be comparable events.

This question might be easier to answer, though: Should police forces decide, on the fly, which protests deserve liaison and de-escalation, and which deserve punishment?

I’ll close by noting that the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police aren’t wandering alone through the doctrinal wilderness with this stuff. The Chiefs’ rough U.S. equivalent, the Police Executive Research Forum, released a paper in February called Rethinking the Police Response to Mass Demonstrations: 9 Recommendations. It says:

“In some cases, existing training may be based on principles of crowd psychology that treat large groups as inherently dangerous. This approach may lead officers to approach peaceful protesters suspiciously, and that may become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If officers generally treat demonstrators as potentially violent agitators, otherwise peaceful demonstrators may feel abused and encouraged to commit acts of civil disobedience or lawlessness.”

The document also says, as you’d hope it would, that it is “also naïve to believe that peaceful assemblies never devolve into violence.” That’s just before the part on “emphasizing de-escalation.”

There’s more, including a body of European police research that draws from the Scottish social psychologist Stephen Reicher, who says things like, “It is precisely in order to stop the violence of the few that one must be permissive towards the many.”

Perhaps I’ve given you enough to consider for today. I’ll let you all discuss the implications. Whether Commissioner Rouleau wants to get into these issues, which may seem distant from the binary question of whether the Emergencies Act should have been used, is his call.

But in a world so shot through with mutual suspicion that office workers are recording or transcribing their own meetings with colleagues, it’s a safe bet that there will be more big demonstrations on highly polarizing issues in the years ahead. So an open conversation about how to handle those demonstrations is on our to-do list as well. Or should be.

Excellent column. The National Framework’s goal that a protest should be allowed to “happen and end” is a sound objective that will hopefully become the standard police response to protests. What’s interesting to me is that the protest basically “happened” on the first weekend. Then it didn’t end. I think the police assumed, as many of us in the city hoped, that the protestors would have to leave town on Monday to go back to their jobs and homes. When it became clear that that wasn’t happening, the police didn’t seem to know what to do next.

Suppose the protestors had stayed, blocking Wellington Street and some surrounding roads, but had otherwise been relatively well-behaved — demonstrating loudly during the day, but also letting people get on with their lives in relative peace. Residents would have found the street blockade a huge nuisance for getting around downtown, but I think most would have accepted that as the price of life in the national capital. Certainly we’re accustomed to detours and blocked roads the rest of the year.

What turned most local people against the protestors was all the things they were doing that weren’t “protesting.” They abused passersby, invaded stores and a homeless shelter, ran their massive diesel engines, and blasted their horns as long and loudly as they could. There is a difference between protesting government actions and being an asshole for the sake of being an asshole — and continuing to do it after you’ve been asked to stop. They’re both perfectly legal. But only one is intended to achieve a political goal. The other is intended to harass people for your own amusement.

That was around the time we stopped calling them “protestors” and began calling them “occupiers.” But I’m not even sure that that was the right word. An occupation is also a political act. At about the ten-day mark, I feel like for most of those gathered in the red zone, the point of the gathering became to hang out, party, blast their horns, use the hot tub, see themselves on TV, and enjoy — really enjoy — the upset they were causing. It wasn’t a protest or an occupation at that point so much as collective untrammeled self-indulgence. They were having the time of their lives. The fact they were making people angry was the cherry on top.

None of this is what Rouleau’s commission is meant to deal with, and I doubt that his findings will touch on these issues more than slightly. It’s important to determine whether invocation of the Emergencies Act was justified. I think Rouleau will find that it wasn’t, because sustained group assholery in a city with a broken police force does not rise to the level of a liberties-suspending national crisis. But the fact that so many of us cheered the Act’s passage as necessary and overdue should probably make its way into his report, even as a footnote, because I think it’s pretty important.

The biggest problem for the police was that they didn't realize they were supposed to be the bad guys.

In Canada, indigenous people are allowed to protest all they like, except that shutting down key linear infrastructure, like the Windsor bridge and the railways in 2020, needs to be ended in a short period of time. Occupying random streets in centres of government (or small towns) is currently allowed indefinitely.

The rules for the convoy were different. Many people in government believed that, because their message was not approved, they should not have been allowed to stay. The OPS mistakenly thought that the rules for protests should be viewpoint independent. Much of the confusion stemmed from the fact that nobody would admit that enforcement is viewpoint-based.

If leadership had said what they were really thinking, eg "all that stuff about liaison and letting people protest applies to indigenous people and environmentalists, but not vax free blue collars - them we bash" there would have been much less confusion. All the drivel about the protest being illegal because it broke parking bylaws is the same - all major protests break those kinds of minor laws. The people talking about parking bylaws are doing it because they are afraid to say what they really think: this protest was different because of who was protesting and what they were saying.