"Worse than I've ever seen"

This week, a three-part series on Alberta's escalating battle against opioids

The story I have to tell you this week is complex, nuanced and important. I tried to tell it in a single post but it’s just too ungainly. This will be the first of three daily* installments.

I had extraordinary access to senior sources in government, police and community service in Alberta — because the people who make a difference know my writing reaches a growing and serious audience. That’s you.

I’m going to leave the paywall off because I want these articles to provoke widespread discussion. Share today’s with your networks here:

You can support my work to tell important stories, travel to where news happens, and pay professional photographers and contributors by becoming a paid subscriber:

“It’s cheque day,” Warren Driechel told me as he drove me through Edmonton’s Chinatown in an Edmonton Police Service SUV. It was the last Tuesday in May. Monthly benefit payments were available to eligible Albertans. In the dozen or so blocks north and east of the downtown Rogers Place hockey arena, that meant more people on the sidewalk, more activity, a generally brighter mood.

More danger, too. This neighbourhood, a mix of Asian restaurants, residential streets built in the early 1900s and drop-in centres for an array of social services, is the epicentre of Edmonton’s drug epidemic. Economic precarity and substance-use disorder go hand in hand here. Gang activity goes with all of that, said Driechel, the Deputy Chief of the Community Safety and Well-being Bureau at the Edmonton Police Service. Especially on cheque day. “They get the money and gangs just swoop in like magpies,” he said. People who need access to medical services, or even just to clean water taps, can find themselves “taxed” by predators.

So for a while, people who needed to use the George Spady Centre on 105A Avenue couldn’t get in without running a gantlet of profiteers. Which only added cost to misery, because the George Spady is a supervised-consumption site where drug users can receive prompt medical attention if the drugs they bring in to inject trigger an overdose. The centre also has 31 detox beds and 10 beds for recovery programs, so people can rest — or take the first steps toward kicking their habits.

Supervised consumption sites, or SCSs, have become common in many large Canadian cities as part of the effort to keep drug users alive. Not all have beds onsite, but in Alberta the United Conservative government is doing everything it can to encourage users to try to get off drugs. Onsite care beds are part of that effort.

Still, even their strongest advocates will say SCSs are no panacea. One clear limitation is that most can only be used for injection, whereas more and more people are inhaling their drug of choice by smoking fentanyl, crack, crystal meth or other substances. Nobody I spoke to was sure why. Smoking may be easier than trying to find a sturdy vein, or cheaper, or more efficient than injecting. But if you can’t do it under medical supervision, it’s riskier.

“It would be good if they could figure out the inhalation piece,” Driechel told me as we drove past the George Spady. As if to illustrate the point, a man was sitting on the curb in front of the centre, smoking something from a glass pipe.

“I should probably talk to this guy,” Driechel said, helplessly. “But…” He shrugged. We kept driving.

I want to be clear that I’m not criticizing DC Driechel, who was as frank to me, and generous with his time, as everybody I spoke to on my trip last week to Edmonton. It’s just that when it comes to stemming the drug tide in Western Canada, you can’t do everything.

The police have been working hard. They’ve become much likelier to enforce rules against open-air drug use than they were a few years ago. They spent much of the winter dismantling tent encampments. That inherently controversial move has forced faster reforms to social services to help the people who were displaced when their tents were taken.

Last fall, working with a leading community health centre, the police opened a sophisticated new holding centre so intoxicated detainees could be put directly in contact with social supports instead of returning to the street and its familiar habits. In January the province opened a “navigation centre” to give homeless people counselling, financial services, healthcare, and the province’s first on-site instant government ID service, so clients can get the identification card that can unlock so many other services.

Today, Alberta has a genuinely impressive story to tell about its efforts to stem the province’s deadly drug crisis. The scale of that effort is more evident now than even a few months ago. In many ways the province-wide response is only now kicking into high gear.

But the scale of the drug crisis in Edmonton and across Alberta makes it hard to be sure of success. Driechel has been in the Edmonton police for 27 years. “It’s worse than I’ve ever seen it,” he said.

Driechel’s assessment was echoed by front-line health care workers I interviewed, and it’s amply reflected in official statistics. I’m not here this week to tell a story of despair. I was impressed by what I saw of the Alberta government reponse to the opioid crisis, which reflects a level of ambition and concerted effort over time that I rarely see in government action anywhere.

But the first thing you need to know is, it’s bad out here.

Tale of the tape

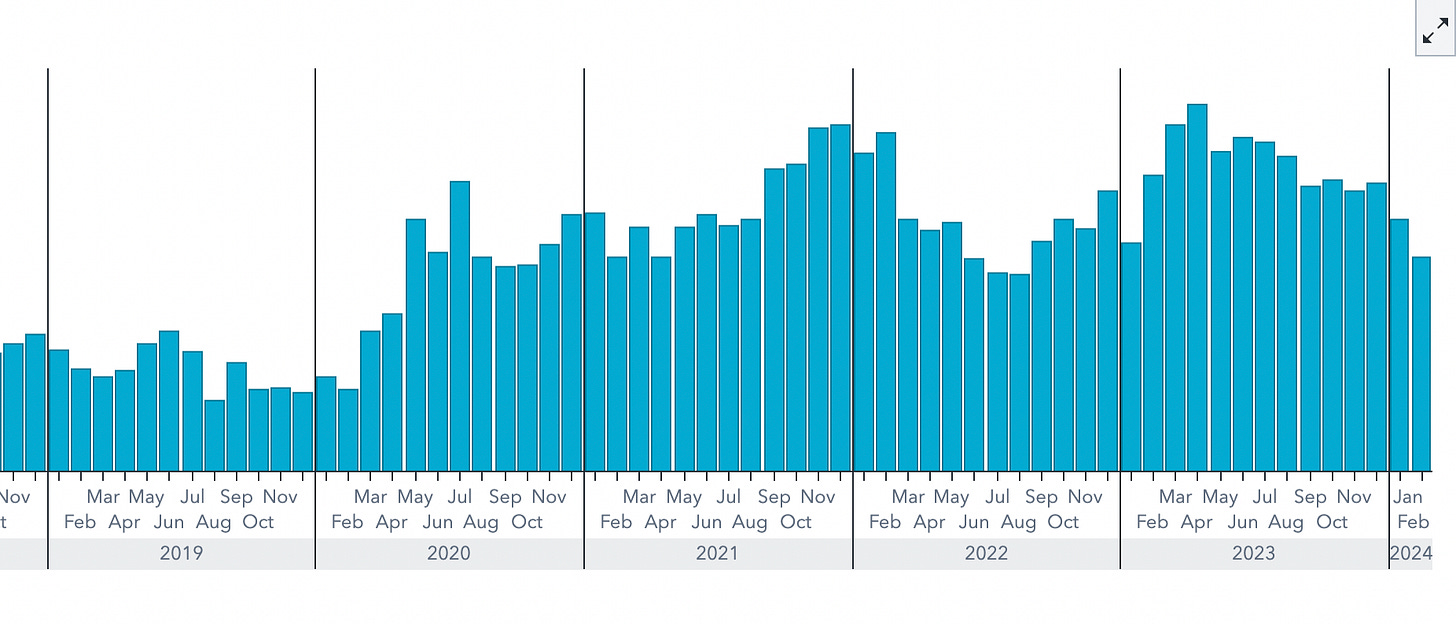

The province’s own statistics bear Warren Driechel’s observation out. Here are monthly opioid fatalities across Alberta from 2019 to the beginning of this year:

Here are the same numbers aggregated annually instead of monthly. 2023 was the deadliest year since records on the province’s impressive statistical dashboard begin in 2016.

Edmonton has a disproportionate share of those deaths. Here are the raw numbers for the province’s capital city. In 2023 they translated to 60.2 deaths per 100,000 person years, one of the highest rates in the country. (Lethbridge, with fewer total deaths in a smaller population, had a higher fatality rate than even Edmonton.)

It’s worth noting that the numbers were lower in the first two months of this year — 109 overdose deaths across the province in February, after bouncing north and south of 150 a month for most of 2023.

Still, one should be cautious about reading too much into a couple of good months. It wouldn’t be the first time someone had done that.

In November of 2022, federal Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre posted a video on his Youtube channel about drugs and tent cities in British Columbia. It followed a Vancouver news conference in which he contrasted British Columbia’s drug policies — decriminalization and safe supply — with “Alberta, where they’ve managed to cut overdoses in half.”

Two weeks later Poilievre published an op-ed in the National Post that doubled down on the distinction between Alberta and British Columbia. “Promising practices are emerging in Alberta,” he wrote. “The results so far are promising, with overdose deaths down around 45 per cent from their peak.” While three months of lower fatality numbers were “not long enough to declare victory,” Poilievre noted, the trend “certainly appears to be moving in the right direction.”

It’s a good thing he didn’t declare victory. By April 2023, overdose deaths in Alberta were up 78% over their lowest level. They stayed high through the year. Poilievre has made fewer references in recent months to Alberta as a model to emulate.

The Conservative leader has stayed on the safer ground of criticizing British Columbia for its two-year experiment with decriminalization of drug possession, and for programs that aim to provide a “safer supply” of opioids to keep users away from toxic, unpredictable street drugs. Facing widespread perceptions in an election year that drug use in BC is out of control, the province’s NDP premier David Eby last month rolled decriminalization way back, essentially re-criminalizing the public drug use that appalls so many people in BC and beyond.

Indeed, the broad political consensus in favour of giving audacious harm-reduction measures a try that existed only a couple of years ago has collapsed, not only in BC but in U.S. liberal bastions like Oregon and San Francisco.

(More background on those two states here. In B.C., the best writing about the shifting politics is in this post on Substack from Geoff Meggs, who was chief of staff to former NDP premier John Horgan. Highlights from Meggs’ post: “Public patience has run out. … What could possibly go wrong? Just about everything.”)

Trudeau’s government, too, is in full retreat, refusing a request from Toronto to decriminalize simple possession.

I’ve indulged a long detour into the rhetoric of Pierre Poilievre because there’s a good chance he’ll be Canada’s next prime minister, and because he has worked hard to cram the policies of two provinces in the throes of a major public-health crisis into a recklessly simplistic frame. Both provinces pursue harm reduction. Both offer treatment to aid recovery. Both have police forces who must decide how to balance enforcement and help. Increasingly, the differences between their approaches deserve a debate, but caricature doesn’t help. When Poilievre writes that “Trudeau’s wacko policies have killed 42,000 Canadians” — a figure that refers to the total number of opioid-related deaths across Canada since 2016 — he encourages the belief that things will magically get better if one politician loses his job. Which, if anyone believed it, would set them up for bitter disappointment later. It’s irresponsible.

But just as the scale of the challenge persists, whatever rhetoric a distant politician indulges, so does the scale of the response. And the response is worth our attention.

Tomorrow: The Alberta model

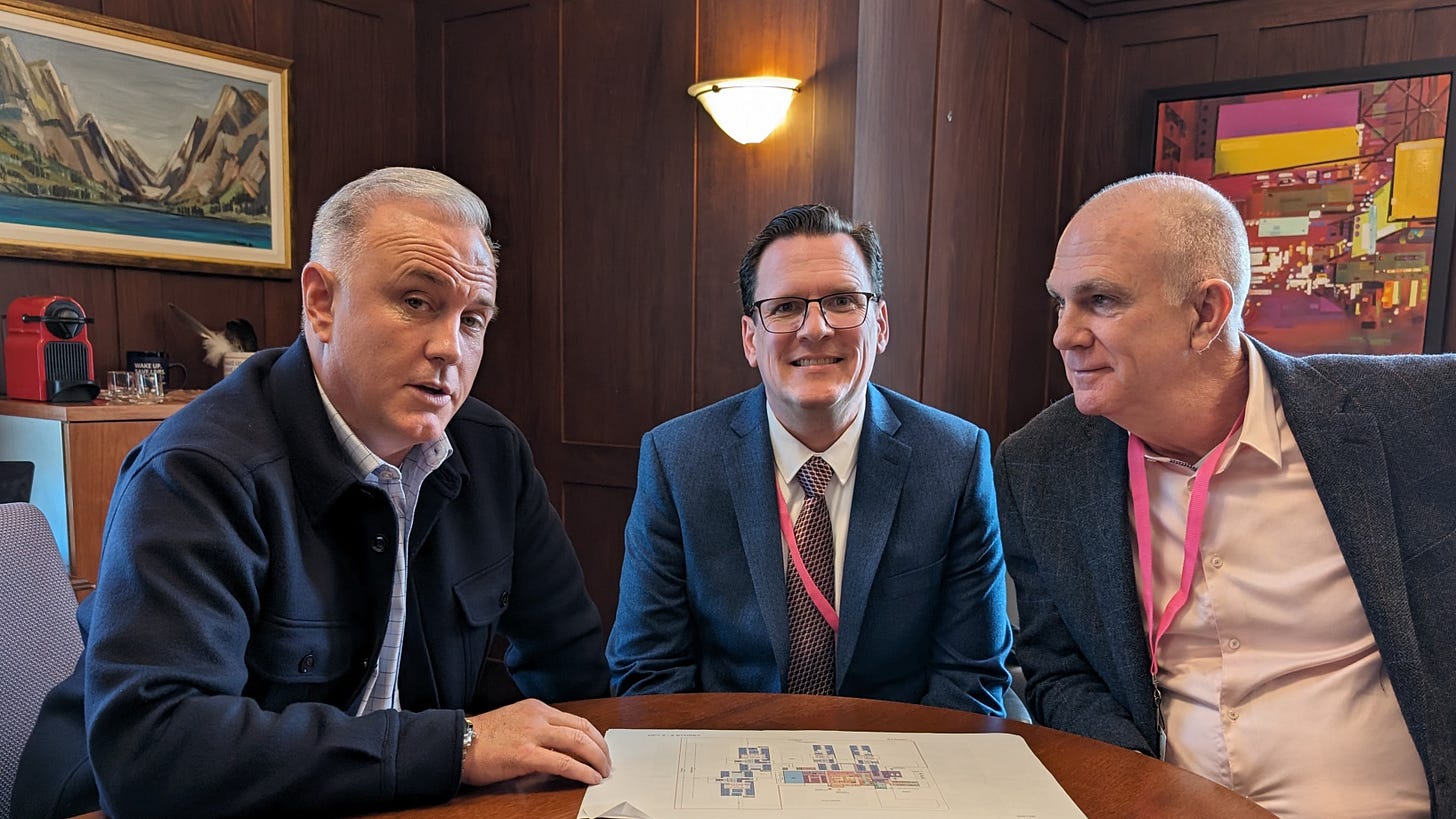

By now many people who follow Alberta’s response to the opioid crisis have heard of Marshall Smith. He’s the chief of staff to Alberta Premier Danielle Smith (no relation.) Since several years before she became premier, he’s been the main architect of the province’s anti-overdose strategy, dubbed “Recovery-Oriented Systems of Care,” or ROSC.

He has a fascinating personal history, chronicled most recently in a Globe and Mail cover feature two weekends ago. Smith is an addict in recovery. His early adulthood was a story of cocaine and methamphetamine use, homelessness and incarceration. He’s disarmingly relaxed about discussing that harrowing past life.

Smith takes these issues seriously because he’s lived them. Some of his critics worry he is too eager to generalize from his own experience, which ended well, to assume others can expect the same. My own view is that we could litigate that question until the cows come home, but to some extent it would distract from the extraordinary government-wide effort to transform Alberta’s response to its overdose crisis.

This is a policy and governance story, in other words, not only a human story.

I’ve been covering politics for 30 years. I haven’t often had an experience like the one that began when I emailed Smith to tell him I was coming to Edmonton. This was just before lunch on a Thursday, four days before I was to arrive. Within an hour, Smith cleared his entire schedule for the following Wednesday and arranged a road trip to illustrate the province’s recovery effort. In a world where it can be difficult to wrangle nine-word answers from political staffers, this one decided at the drop of a hat to give me nine hours.

Tomorrow* I’ll tell you what he showed me.

I appreciate your links to good articles on the current state of affairs elsewhere and especially BC. There's a lot of clutter without clarity in the media, perhaps understandably, and I tune out when there's little opportunity for better understanding. Looking forward to your next two articles.

i cut my professional teeth detoxifying newborns from heroin, alcohol, and methadone, hundreds upon hundreds of them, in a public hospital nursery 30-40 years ago, pre-fentanyl. incidentally, having observed far more newborns exposed to crack cocaine than opioids, there is no newborn cocaine withdrawal syndrome. on the other hand, a learning disorder is almost guaranteed.

some people who see the particular suffering of opioid dependence in people of any age get an intense desire for redemption and rescue. be careful. this nut is very tough to crack. it ain't going away any time soon.

having been professionally immersed in the crack and heroin-related hiv epidemics simultaneously many decades ago, i don't think that everybody is susceptible. it might seem "viral", but i do not think it really is. it does seem like that though at times.

in nyc giuliani's goons did NOT not make the DECISIVE difference for the partial resolution of the crack epidemic. i think it "burned itself out", in part. those communities organized themselves, socially and culturally at the neighborhood and community level, to reject crack cocaine and heroin and eventually younger people in particular simply went another way.

but, be assured, there was no rescue. far too many adolescents and pregnant women are now using cannabis. far too many people are still drinking large amounts of alcohol, daily. massive numbers are dependent on the xanaxes of the chemical world. and yes, EVERYTHING should be legal.

so while everybody searches for quick resolution have patience, as hard as that is to conjure. believe me, i developed a serious case of desperation as i watched all those newborns roll through my nursery, puking, shaking, sweating, screaming, plus plus.

the reflex of abandoning a more public health approach and returning overwhelmingly to policing at this point is a mistake. law enforcement will be necessary, but neither the law nor religion will solve this. nevertheless, all approaches will be necessary. above all be patient and be careful. anti-opioid missionaries are less than useful in the long run.

unless of course, you are desperate enough to go the way of the philllipines and el salvador and, folks, that is a COMPLETELY different discussion.

incidentally, alcohol is a far larger problem. certainly the toxicity level for any given fetus is far higher than for other "hard" drugs. Fetal alcohol exposure is considered to be at the very top of any list of causes of intellectual disability. some think it is the leading cause.

and as canucks, always remember that y'all have been "sitting" on close to genocidal levels of substance use amongst 1st nations peoples for decades and doing "jack" about it. to some extent fentanyl is a big deal now because white people are in the middle of it.