I’ve been meaning to discuss the federal opposition leader’s scrum in Vancouver last week. The convoy commission and other events keep distracting, but I don’t want to let Pierre Poilievre’s comments pass unremarked.

This was Poilievre’s “Everything seems broken” scrum, and a lot of it is worth everyone’s attention. His opening remarks put him on solid electoral ground: the generalized sense that society is in disarray and the current government can’t do anything about it. It’s a pretty standard opposition line, and its effectiveness will depend on whether voters feel it’s true when an election comes.

There’s one thing I want to point out in passing, and another I want to discuss at length, even though it’s not the sort of thing that would move a lot of votes.

First, Poilievre is asked repeatedly about his support for the convoy that parked in Ottawa for three weeks in February, and for copycat blockades elsewhere. He’s categorical. “I support those peaceful and law-abiding protesters who demonstrated for their livelihoods and liberties, while condemning any individual who broke laws, behaved badly or blockaded critical infrastructure,” he says. “I think it’s possible to support the overall cause of personal free choice in vaccination and the overall cause of respecting the truckers’ ability to earn an income, while holding individually responsible anyone who behaved badly, broke laws, or blockaded key infrastructure. That was my position before, during and now.”

It’s always handy to listen to what a person is actually saying. It’s easy to understand all the attention to the first part of Poilievre’s answer, the “I support” part. But the second part seems significant too. Once you start “condemning any individual” who breaks laws, “behave[s] badly,” my goodness, or “blockaded key infrastructure,” you may have a beef with a lot of individuals. And you may find that prosecuting that beef requires some ambitious action. It strikes me as a loophole you could drive a truck through, you should pardon the expression.

But mostly I want to talk about Poilievre and opioids. “BC has had a 300% increase in drug overdose deaths since Trudeau took office,” he says. A Poilievre government would “put an end to this taxpayer-subsidized program of paying for people to use dangerous narcotics and instead put that money into safe recovery programs to help our addicts get off the street, break their addiction, rebuild their lives. Just like they’re doing in Alberta where they’ve managed to cut overdoses in half.”

To me this answer shows a lousy understanding of substance-use policy in British Columbia and Alberta and a strange conception of federalism. It suggests Poilievre would pursue policies that would likely make opioid deaths increase.

Let’s break it down.

“A 300% increase in drug overdose deaths”

Justin Trudeau became PM in 2016. The federal health department says opioid-related deaths in B.C. went from 806 in 2016 to 2,291 in 2021, 2.84 times as high. That’s not a 300% increase, but it’s a near-tripling. So, close enough. It’s churlish to ask for precision in off-the-cuff remarks.

The same federal statistics say Alberta opioid deaths went from 602 in 2016 to 1,618 in 2021, so 2.69 times as high. That’s close to the same growth.

“In Alberta where they’ve managed to cut overdoses in half.”

There is indeed something happening in Alberta. From the province’s excellent data portal on substance-use statistics, we get this chart:

That’s “drug poisoning deaths by month,” province-wide. Raw numbers, not a rate as a proportion of population (though that’s available too — it really is a good dashboard). We see that in July 92 people died of suspected overdoses, down from the highest-ever number of 174 in November of 2021. That’s progress. Unfortunately 92 is more deaths in any month before May, 2020. In other words, drug deaths spiked during COVID, for reasons that are tragic and easy to understand — isolation, a massive diversion of health-system resources — and are returning to a still-elevated level.

“Just like they’re doing in Alberta”

Here we get to the question of how Alberta has managed to get the numbers down. Mike Ellis, who was Jason Kenney’s associate minister of mental health and addictions, likes to say Alberta’s system is more “recovery-oriented,” and that notion has gotten excellent press. “If we're doing a direct comparison, the supervised consumption sites are only one part of a very complex problem. And ensuring that we get folks into detox treatment and recovery and doing the hard work so that they can live happy, successful, healthy lives again — that's the hard part," Ellis told the CBC.

Without asking — although that interview request remains open and eternal — I’m pretty sure this is where Poilievre gets his distinction between “this taxpayer-subsidized program of paying for people to use dangerous narcotics” on one side of the Rockies, and “safe recovery programs” on the other.

But you know, it’s a funny thing.

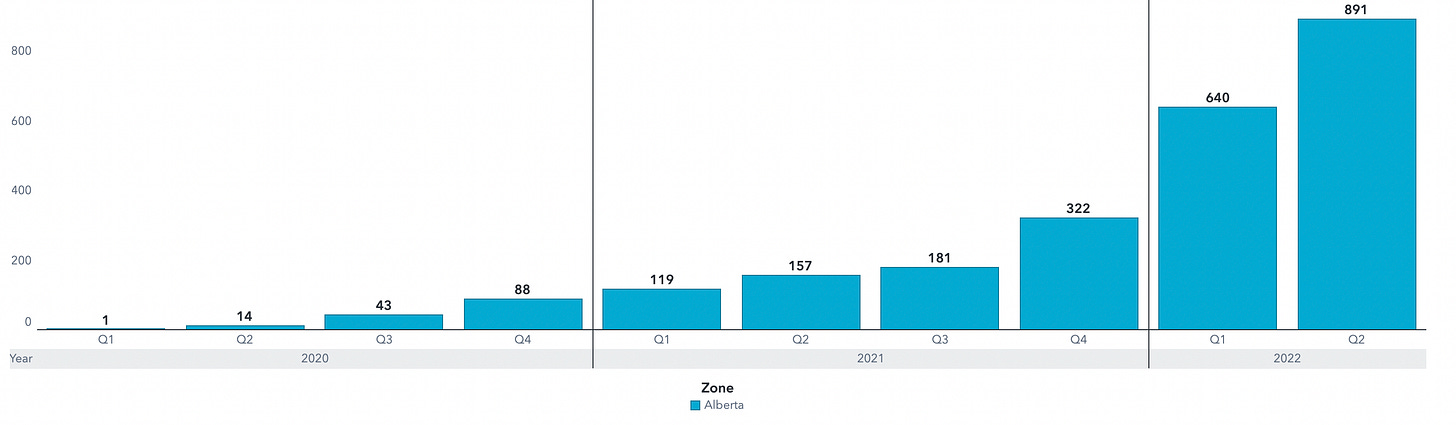

From the same Alberta government data portal, here’s the growth in the number of Albertans who receive buprenorphine/naloxone tablets, long-lasting opioid doses that sharply reduce the craving for street drugs:

And here’s the number of Albertans getting methadone from the government:

Here’s community distribution in Alberta of naloxone, which powerfully blocks the effect of opioids and makes overdoses survivable:

And here’s the very rapid growth in the use, by Alberta health services, of injectable buprenorphine, or Sublocade, for patients with a documented history of drug use who haven’t been helped enough by other approaches.

That’s from one patient to 891 in a year and a half. Sublocade blocks the receptors that other opioids act on; it can make patients feel disoriented but reduces cravings without offering a high. But of course the drug’s own manufacturer admits a “serious risk of potential harm or death” from improperly using it. Pilot programs for another injectable, hydromorphone, are coming soon in Edmonton and Calgary.

Finally, here are the five Alberta cities where the government runs supervised consumption sites, where people can come in and use their own injectable or smokable substances.

Why does Alberta run all these harm-reduction services? For the same reason B.C. and other Canadian jurisdictions do: because they save lives. I was at Vancouver’s Insite supervised-consumption site in 2018 when a man overdosed. Insite staff gave him naloxone; he was rattled but recovering by the time an ambulance arrived. I’m not used to these things and I found the episode, which is common at such facilities, unsettling. But here’s the thing. At Insite and other supervised-consumption sites, in B.C. as in Alberta, overdoses are never fatal. In 2022, 1,644 people died of overdoses across B.C. from January to September, the B.C. Coroners Service says. But “No deaths have been reported at supervised consumption or drug overdose prevention sites,” and “there is no indication that prescribed safe supply is contributing to illicit drug deaths.” Same story in Alberta.

Incidentally, “our addicts” often aren’t on the streets: 56% of overdose deaths in BC so far in 2022 happened in private residences, the BC Coroners Service says. This is what the choice often comes down to: survive in supervised-consumption sites, which do often have activity outside them that spoils neighbours’ sense of an orderly city; or die demurely indoors from an overdose nobody was around to stop.

Apart from the fact of not dying, what else is a supervised-consumption site good for? Well, while they’re not dead, some patients at those sites get referred to programs that can help them get medical care, housing and mental-health support — the sort of thing that might help their lives improve. Many are likelier to take this advice because it comes from people who are in the long-term business of helping them avoid dying and otherwise care about them. The federal government, using spotty data, suggests there were 70,000 such referrals from 2017 to 2019, or 3.5% of all visits. That’s a low intervention rate. But have you ever tried to make somebody give up a habit who didn’t want to? Success rates are low.

“…instead put that money…”

Finally, I wonder how Poilievre thinks Canada works.

“This taxpayer-subsidized program of paying for people to uses dangerous narcotics” is, of course, several programs, almost all of which are run by the government of British Columbia, the government of Alberta, and most other Canadian provinces. Elsewhere in his Vancouver scrum, Poilievre properly accused Justin Trudeau of ignoring provincial jurisdictions. Is he planning to take over health care and municipal policing?

Of course, this being Canada, jurisdictional lines are never entirely clear. The federal government does run a “Substance Use and Addictions Program,” SUAP, as you might hope it would in the face of a massive killer of Canadians. Here’s a searchable database of the activities it pays for. The largest amount of money, $10.2 million, goes to St. John’s Ambulance for naloxone kits and training for ambulance crews, so fewer people will die within minutes of ambulances arriving. There’s $8 million for a similar program with the Canadian Red Cross, about $6 million each for safe supply in Toronto and London, ON, $5 million so Fredericton can have “opioid agonists” — buprenorphine and Sublocade just like they’re doing in Alberta, and so on.

A future federal government would have complete latitude to divert SUAP funding from harm reduction to “safe recovery programs,” defined apparently very differently from what they’re actually doing in Alberta. I look forward to a discussion longer than three sentences with any candidate for prime minister who would like to do that. But let me be blunt. If an ambulance crew arrives in the middle of an overdose and gives the patient a pep talk instead of naloxone, the patient’s likelihood of dying will skyrocket. This sort of thing is worth thinking about, when applying for important responsibilities.

Thank you so much for this piece.

Recovery is only possible if you’re alive, which is why harm reduction is so crucial.

Like many people I was against the safe injection sites in Vancouver but then I realized that it was preventing people dying period not about being soft on drugs or paying for addicts drug habit. Granted it is not The solution but part. Addiction is a complex issue. Maybe bringing the provinces together looking at what data they have from their programs might be helpful. Not convinced though that the feds have much to contribute.