(This is the second chapter in The End of Media, a series of connected essays on politics and communications. For Chapter 1 in this series, Went Down to the Crossroads, click here.)

On Jan. 26, 2006, almost 13 years of Liberal government ended when Stephen Harper’s new Conservative Party of Canada won just enough seats to form a minority government. Harper got into disputes with the Parliamentary Press Gallery almost immediately. The gallery “has taken the view that they are going to be the opposition to the government,” the prime minister told a local TV interviewer in London, Ontario, four months after the election. “We’ll just take the message out on the road. There’s lots of media who do want to ask questions and hear what the government is doing.”

What Harper couldn’t yet know was that “the road” — understood as the list of places were anyone could take their message — was about to expand beyond recognition.

Eleven months before the 2006 election, a service for posting home video online launched in San Mateo, California. Its name was Youtube. Two months after the election, Jack Dorsey published the first Tweet: “just setting up my twttr”.

A few weeks before the first anniversary of Harper’s election, in January 2007, Steve Jobs announced the first iPhone. Its opulent capabilities made it a bandwidth hog, putting such a burden on delicate cell-phone networks that the founders of the then-dominant smartphone platform, Blackberry, thought Jobs had made a self-defeating blunder. In October 2007, Microsoft paid a quarter of a billion dollars for a sliver of Facebook, implying that the fledgling online message-board service was worth $15 billion.

Netflix, which had until now worked by mailing DVDs postage-paid to its customers, announced early in 2007 that it would now transmit movies digitally via internet. Instagram, a relative straggler in the social-media sphere, launched late in 2010.

These platforms took years to establish their worth, but Canadian politicians were early adopters. Staff at the French Embassy in Ottawa were accustomed to thinking of Canada as a lovely place but maybe a bit behind the trends. They were amazed to see Harper’s government posting important policy announcements on ministers’ Twitter accounts before they appeared anywhere else. And then, before long, on Twitter only. For one of Harper’s cabinet shuffles, the government tweeted out the names of new ministers before reporters at Rideau Hall could see who’d shown up for the ceremony.

The new social-media platforms were intriguing in themselves, but it was the new generation of Apple and Android smartphones that made them a societal force. The bandwidth demands that seemed like such a mistake to the competition at Research In Motion simply forced service providers to increase their capacity. Pretty soon you could run just about anything through your phone, even movies.

These developments made portable phones the most fascinating objects their owners possessed. Everything else felt old. NBC’s Today show tweeted photos from St. Peter’s Square showing the announcements of two Popes, Benedict in 2005 and Francis in 2013. Spot the difference.

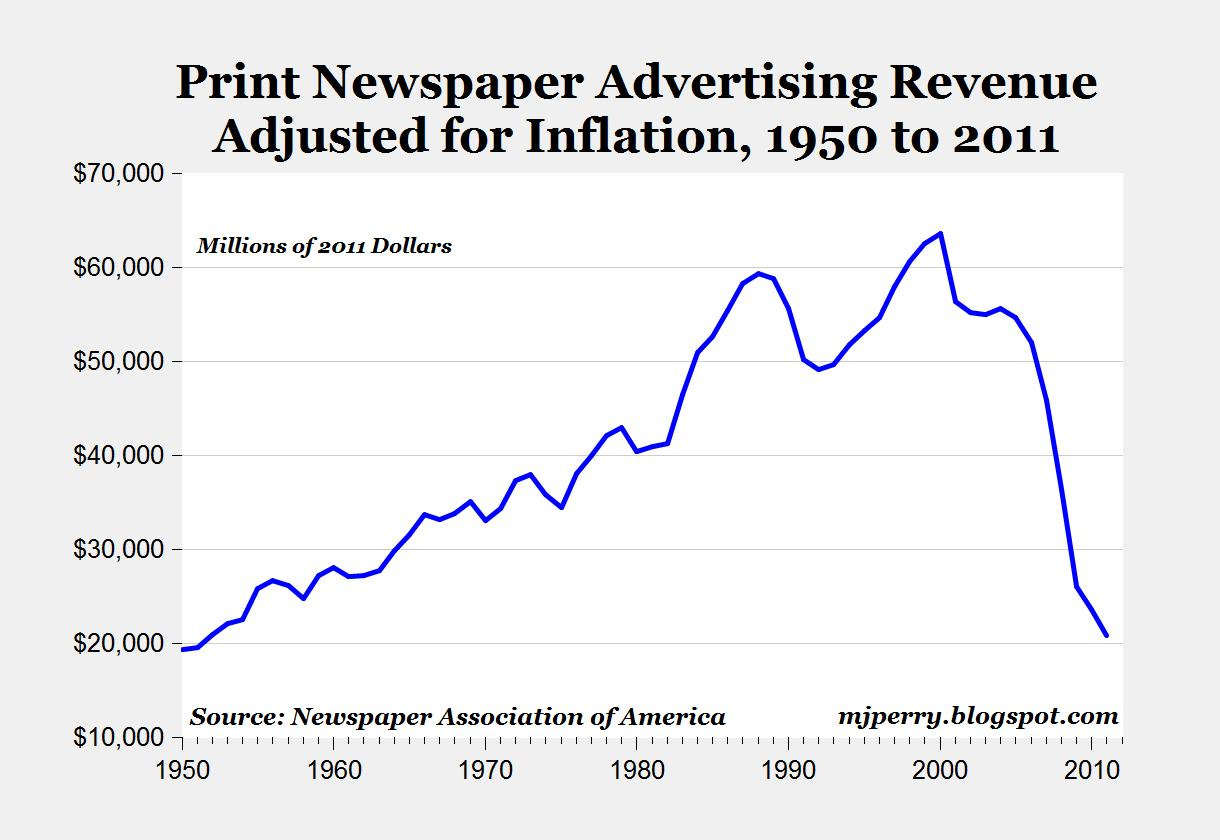

Pretty soon, if your content wasn’t on a phone you were in trouble. From 2004 to 2007, Maclean’s magazine had worked hard to boost newsstand sales with catchy and sometimes controversial cover designs. The strategy was paying off. Newsstand sales grew steadily. Then, beginning in 2008, they fell off a cliff. The main reason: People carrying iPhones no longer felt the need to buy a magazine before they boarded a flight. Industry-wide, print advertising revenues had already been in free-fall for a decade…

…but now the act of picking up any piece of printed material was endangered.

These changes made life hard for big news organizations and unpredictable for journalists. They still do. But their effect on journalism was probably less significant than their effect on the way every large organization thought about communicating.

Not only was the amount of information available to (just about) anyone (in rich countries) exploding, the amount of information anyone could produce was increasing on a comparable slope.

The result was the most overwhelming information glut in history. It’s still going on.

“Five exabytes (or five billion billion bytes) of data could store all the words ever spoken by humans between the birth of the world and 2003,” the Harvard Business School economist Bharat Anand wrote in his 2016 book The Content Trap. “In 2011, five exabytes of content were created every two days.”

This meant that anyone in the communications business was now shouting into a hurricane. “Compete in a world of four broadcast channels and you know what you’re up against,” Anand wrote. “Compete against 900 channels, millions of short-form videos, and the rerelease of an entire library of video archives — including your own — and it’s a strategic and marketing nightmare even to make consumers aware of what you’re producing. Let’s call this ‘the problem of getting noticed.’”

I began this chapter by mentioning Stephen Harper. He was a polarizing figure. But to some extent, in the context of today’s discussion of the media environment, your feelings about him are a distraction. What’s germane is that Harper’s election coincided, in the purest sense of “coincidence,” with the dawn of a revolution in communications. A historic revolution of immense scale, with repercussions that are still only beginning to be understood.

Three-quarters of today’s post lies below this paywall. This newsletter is my full-time job. I’m grateful for the support of readers who chose to become paid subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paul Wells to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.