I’ve been preoccupied lately with the decline of two sectors this newsletter watches closely: media and government.

Every week brings word of some new catastrophe in the industry I used to inhabit, the industry of large news-gathering organizations. Revenues and market penetration have been in free-fall for so long that you’d think free-fall would have gotten old by now. And yet it continues. This month Bell Media showed that the abrupt dismissal of Lisa LaFlamme in June 2022 was merely proof of concept. The telecoms giant cut 1,300 more jobs a year later, without apparent regard to anyone’s hair colour, and is asking for regulator permission to keep going. Management turmoil is the order of the day at beleaguered Postmedia and (a close cousin to the news business) beleaguered Indigo. My alma mater, The Gazette in Montreal, is not doing well. Torstar’s had a hell of a year. I could go on. There is no shortage of examples. A new one broke while I was writing this.

Meanwhile governments are becoming worse at communicating, even as they become more obsessed with communications. Or rather, they’re getting better at saying less. The federal access-to-information regime is a sad joke. Ministers’ answers in news conferences and in Parliament are often empty slogans. They face triple, triple triple the inanity across the aisle. Political leaders pare back the number of questions they will tolerate when they bother to take any.

The sharply circumscribed limits on real communication seem to pop up well beyond the interface between reporters and the government. When two Globe reporters asked about a government contract with Irving Shipbuilding, the government alerted the company. When staffers thought a story contained errors, they asked Facebook and Twitter to delete it.

And the defensive crouch that characterizes so much of the way governments interact with the world seems to have corroded governments’ ability to communicate even intra muros. Ministers keep finding out about goings-on in their departments only when they become embarrassing headlines.

Nor do these trends seem much affected by governments’ partisan stripe. In Ottawa, the opposition leader’s relationship with news organizations is tense at best and sometimes worse than that. And as with the Trudeau cabinet, the Conservative caucus apparently has problems with its internal communications.

So far I’ve been engaging in two kinds of shop talk, sharing the complaints of the media bubble and of the Ottawa bubble in turn. But you don’t have to live in Ottawa to feel some of what I’m describing.

A sense that modern communications doesn’t communicate. That it’s massively unidirectional: it’s a mechanism for sending message but not for hearing people. That even as the number of people employed in “public relations” skyrockets, our public relations — the extent to which we get along and feel heard and understood, the health of our democratic life — stagnates or collapses.

I’ve been thinking about all this so much that it’s probably time to share some of my thoughts with you. This is the first in a series of connected essays that will stretch across the next several days in this newsletter. I’m calling it The End of Media.

The last word in that title is precisely chosen. I know this will sound like navel-gazing. But I think the decline in news organizations’ fortunes and the decline in the quality of our democratic life are connected.

It’s not a causal link. I don’t think our democratic life is unsatisfying because Big Media has been cast out from the heavens. And I certainly don’t think the remedy for our ills is to support absolutely any harebrained policy that would put the largest and oldest news organizations on life support. Surely by now it’s becoming obvious that such policies are futile. I’ve believed for years that they’d be wrong-headed even if they worked.

Rather, I think the decline in our industrial communications and the decline in our democratic give-and-take are two effects of a third cause, which of course is the rise of the internet and social media. You used to need people like me to tell you what was going on. Now you don’t.

Economists have a word for this sort of change: disintermediation, the removal of intermediaries. Or of media. The elimination of gatekeepers, to borrow a loaded term. As the tech-bro philosopher Balaji Srinivasan wrote in an odd little book that finally gave me a word for what I’ve been observing all my adult life:

“[T]he internet connects people peer-to-peer. It disintermediates. In doing this it removes the middleman, the mediator, the moderator, and the mediocrity. Of course, each of these words has a different connotation. People are happy to see the middleman and mediocrity go, but they don’t necessarily want to see the moderator and mediator disappear. Nevertheless, at least at first, when the internet enters an arena, once the Network Leviathan rears its head, this is what happens. Nodes that had never met before, could never have met before, now connect peer-to-peer.”

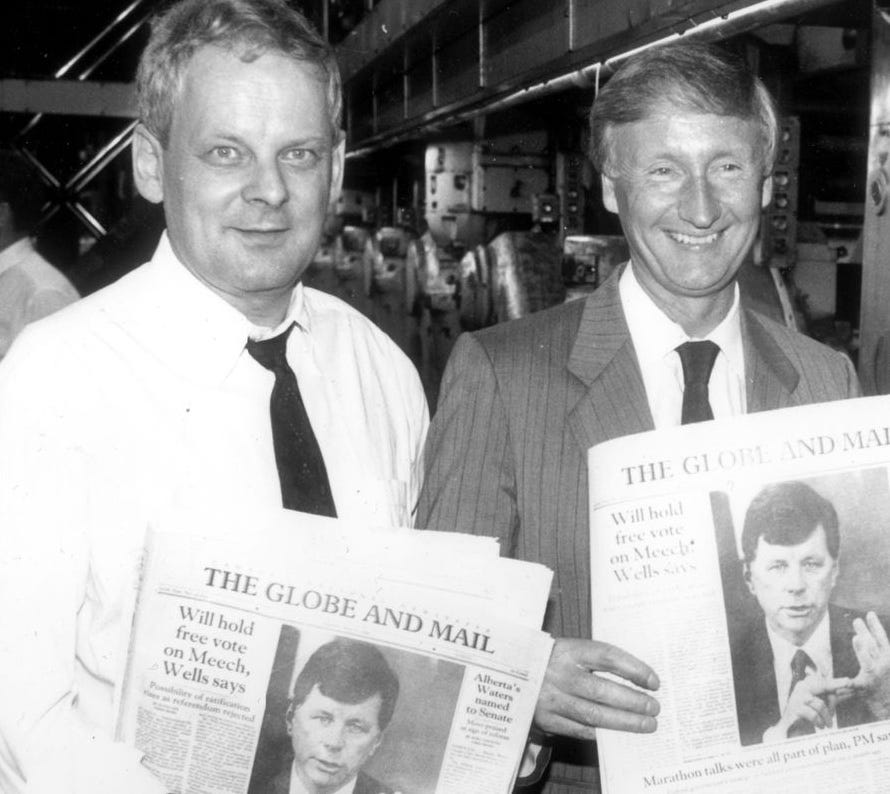

My goal over the next several posts will be to examine what happens to our communications, and therefore to our polity, when everyone can communicate for themselves. But first it’s worth remembering what it used to be like, before the media were disintermediated, when the gatekeepers still had gates to keep.

The main point of this stroll down memory lane will be to point out that the pre-internet era was an aberration too, a genuinely odd confluence of forces that turbo-charged big news organizations’ ability to dominate democratic conversations.

It couldn’t last. I’m not sure we’d go back if we could. It can’t be replicated with simplistic policy band-aids. And if our leaders were honest with themselves, they would admit they wouldn’t go back if they could.

Seven of my last 10 posts were free to all subscribers. This one, and the others in this series, will be paywalled, for a couple of reasons. First, because I want to reassure my paying subscribers that they were in fact paying for a higher tier of access and content. Second, because I’m putting everything I know into this series, and I’m here to tell you, it feels like work. I’m grateful for everyone’s attention and support. You make me want to do my best work. Two-thirds of the words in this 3,000-word post lie below this paywall.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paul Wells to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.