I’ve been reading Peter S. Goodman’s Davos Man, a tough, angry — not entirely persuasive — critique of the sort of people who get top-level access to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Because Goodman’s vantage point is left-by-centre-left, his book provides fascinating counterpoint to a polemic about the WEF that is, in Canada, the almost exclusive preserve of the right.

Here’s Pierre Poilievre calling on People’s Party leader Maxime Bernier to disown the WEF. The NDP-linked Press Progress website dug up the video, which wasn’t hard to find: it’s been shared 170,000 times on TikTok.

“I’m against the World Economic Forum,” Poilievre tells a questioner who wants to hear him say precisely that. He adds: “Unlike Maxime Bernier, I’ve never been to the Davos conference that the World Economic Forum puts on. And he’ll have to explain why he went there and what he was doing there. But I did not go to that, and I would not go to it, nor will any of my ministers.”

We have thus entered the coveted “Davos is Cooties” phase of the debate. Bernier, who was already facing questions about a 2008 trip to the big conference, when he was a minister of the Crown, is actually way ahead of Poilievre. Here he is admitting that yes, he was in Davos, but insisting he didn’t listen or speak to the bad people, he’s “not a globalist,” and he won’t go back once the PPC forms a government.

At the outskirts of the Conservative leadership process we find Joseph Bourgault, who tried but apparently hasn’t qualified as a CPC leadership candidate. In one video we see Bourgault inviting former hockey star Théo Fleury up to accuse Poilievre of being in league with the WEF. Fleury uses salty language and makes frequent reference to “they.” Apparently one knows who they are.

Here we have Leslyn Lewis, who has qualified as a CPC leadership candidate, saying that “one of the most common questions I get” as she travels the country “is about the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Prime Minister’s post-national ambitions, and the threat of Digital I.D.” She clearly isn’t the only one getting questions. Andrew Scheer demanded the WEF take his name off its website. Here Scheer insists he wants nothing to do with the thing.

Clearly the approved answer is that Davos is not to be touched. This seems to be a late development, as Ed Fast, Jim Flaherty, John Baird and Stephen Harper (twice!), like Bernier, are among the Canadian politicians who visited some years ago.

What’s harder to find is video of a prominent Conservative this year pushing back against constituents’ urgent questions about the WEF. Almost no matter what the question. Here’s Poilievre being asked whether he’s asked Justin Trudeau about “the amount of money that he is making on these vaccines that he is forcing on us.” “I have not spoken to him about that,” Poilievre replies blandly. “$70 million over two years!” a fellow adds. Poilievre does not respond to that. But that Max Bernier, he’s going to have to answer.

I have many things to say. First, in none of these videos and urgent dispatches is anyone I’ve mentioned carrying out a serious conversation. “I didn’t do the bad thing” and “I think you did the bad thing” are pretty limited answers to questions about a conference that routinely draws the sort of visitor a future prime minister will probably have to interact with. Politicians who make a show of having a problem with Davos should explain what the problem is; why they didn’t raise their concerns when cabinet colleagues were lining up to go; and what solutions, if any, they propose. Otherwise they might seem to be faking their indignation to lure a few votes.

Second, it’s easy to see why Davos catastrophism has taken root in some corners of the electorate. We are coming off a COVID pandemic, after all. Very early, only weeks into this historic disaster, the WEF was quick to start discussing visions of a green egalitarian future with prominent roles for green progressive governments and Davos regulars. This was the “Great Reset,” which I discussed here in a magazine. Soon Trudeau was on video calls saying, “This pandemic has provided an opportunity for a reset. This is our chance to accelerate our pre-pandemic efforts to reimagine economic systems.” Which was jarring. Still is. Soon people were digging up old video of Klaus Schwab, the WEF founder, bragging about “penetrating the cabinets” of Western countries with “Young Global Leaders of the World Economic Forum.”

People who didn’t like everything that’s happened since — vaccines, lockdowns, restrictions — started reading great significance into all kinds of perceived Davos connections. Often Trudeau has seemed eager to help. Replacing his finance minister with the only member of his cabinet who sits on the WEF Board of Trustees, while yet again blathering on about how “we can choose to embrace bold new solutions to the challenges we face and refuse to be held back by old ways of thinking” was… loopy, sure, but it probably only accidentally resembled the second act of a Bond movie.

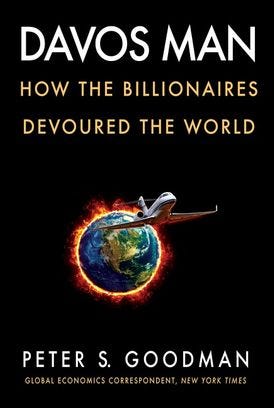

Bringing an element of novelty to all this is Peter S. Goodman, the Global Economics Correspondent of the New York Times. Even if he were Canadian, nobody should expect Goodman to support Poilievre for Conservative leader. Davos Man is a furious diatribe, not against the WEF as an institution but against many of Davos’s richest regulars — and it’s written from a consistently social-democratic perspective.

From its subtitle, “How the Billionaires Devoured the World,” Davos Man relentlessly skewers some of the most glamorous Davos habitués — Amazon gillionaire Jeff Bezos, Blackstone founder Stephen Schwarzman, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, banker Jamie Dimon, Salesforce guy Marc Benioff. And their, you know, ilk.

“Over recent decades, the billionaire class has ransacked governments by shirking taxes, leaving societies deprived of the resources needed to combat trouble,” Goodman writes. Davos Man — Goodman has borrowed the term from Samuel Huntington — “is a rare and remarkable creature, a predator who attacks without restraint… expanding his territory and seizing the nourishment of others.” Goodman’s language is consistently violent. The billionaires “eviscerate financial regulations,” “defenestrated antitrust authorities,” “squashed the power of labor movements.”

COVID takes up much of Goodman’s book and is indeed a historic example of the rich getting richer while the poor, especially in the U.S., lost jobs, benefits and often their lives. Goodman’s last chapter begins: “Other people could tally the dead. Steve Schwarzman was too busy counting the money.”

I don’t find Davos Man an entirely persuasive critique of Davos, man. Goodman acknowledges from the outset that the title term is “a catchall.” His lead characters’ deregulating, system-rigging, subsidy-farming, gated-community plundering of nations in crisis is usually only tenuously linked to anything that might have happened during actual World Economic Forum conferences in Swiss mountains. If someone is a monstrous plutocrat who was once spotted in Davos, to Goodman that it enough to make him (it is always a him in this book) a Davos Man. The most vivid hints that Davos might itself be a problem, rather than just an R&R weekend for plutocrats, comes when Donald Trump comes to Davos and all the regulars fawn over him, thanking him for his massive tax cut, which savaged the American government’s ability to help shelter ordinary people from a calamity.

Here we are reminded that Goodman’s politics are far from the politics of most Canadian WEF obsessives. He wants governments that live up to Trudeau’s and Freeland’s rhetoric. He views Trump, Brexit and tax-cutting governments in Italy and Sweden as the problem. Worse, as profiteers, parading as remedies to the ills besetting ordinary folk while they drive inequality deeper.

But this blue-chip member of the media elites is so furious at the way the world’s self-appointed guardians have made big problems worse that he implies a question: is it entirely fair to write off the fears and resentments of others, just because they don’t have a sophisticated or league-approved vocabulary to discuss the injustices they perceive?

I’ve never been to Davos. For years I’d have gone if asked. Now I’d probably skip it. Probably. I always thought of Davos as an overpriced weekend getaway conference, vastly out of scale with conferences I’ve attended in Canada but not different in kind. This is the portrait Conservative MP Michelle Rempel Garner drew in an article for The Line that I found altogether braver than the CPC leadership tier’s grotesque Alphonse-Gaston routine. But maybe that’s letting the WEF, and the people there with the best passes, off the hook too easily. Some of Chrystia Freeland’s colleagues on the Board of Trustees got spectacularly richer while their society was suffering hurt on a historic scale. For that happy few, the building back better didn’t have to wait.

Freeland’s actions sometimes suggest she understands that a burgeoning sense of injustice deserves a policy response. The global minimum corporate tax, for one thing. The latest budget’s stiff bank tax, for another. It probably won’t change many minds, but it suggests awareness at least. If Freeland were to explain, thoughtfully and in some detail, why she’s on that Board of Trustees, that might help too. But Ottawa isn’t really that kind of city these days.

A strong piece. Such a pleasure to read beneath the bad-Davos caricatures.

Great read! It’s a shame the discourse in Canadian politics doesn’t always welcome these nuanced critiques of WEF and the current government’s support of it.