The Q&A: Trillion-dollar love affair

Patrick McGee on his astonishing best-seller, Apple In China

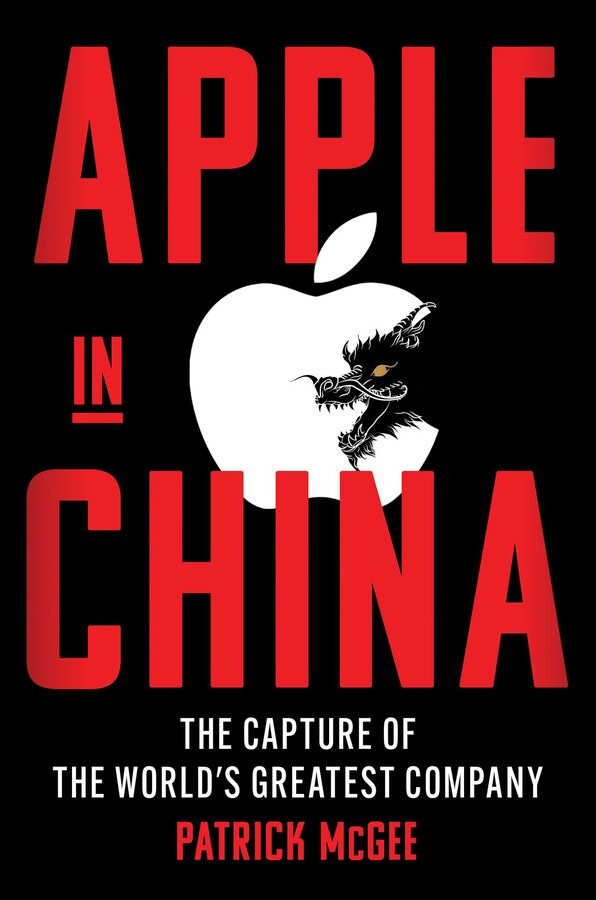

Three things happened to make Patrick McGee’s new book, Apple in China, one of the most talked-about books of the year.

The second thing was that Jon Stewart had McGee as a guest on The Daily Show, which doesn’t happened to every tech author. Stewart raved about the book.

The third thing was that Donald Trump threatened Apple with a company-specific tariff if it doesn’t move production back to the United States from China. Which did wonders for a brand-new book about how Apple got into China. “I call Donald Trump my chief publicist,” McGee told me.

But the first thing that happened was that McGee wrote a deeply readable and important book. This isn’t a polemic or a harangue about why you should feel bad about Chinese authoritarianism or shareholder capitalism. It’s a methodically reported, step-by-step history of the element in the Apple story that usually gets ignored: not the personalities of Steve Job and his followers, or the clever designs of the products, but how they were built. By whom; where; and at what snowballing and breathtaking cost.

McGee is the San Francisco correspondent for The Financial Times, and was for many years the great newspaper’s lead Apple reporter. His assertion is that not only did China make Apple the company it is today, but that Apple made China the country it is today. Except it’s not really an assertion, because he shows how it happened rather than claiming it happened, and you’ve read most of the evidence before he makes the claim. And you’ve read hungrily, because it’s a ripping good yarn.

I started reading this book because the topic seemed worthy. It’s become one of my favourite books, on any topic, in recent years. McGee and I spoke by Zoom on Thursday. The transcript was edited, mostly by my patient producer Suzanne Hancock, for length and clarity.

Paul Wells: So, Patrick, you’re Canadian.

Patrick McGee: I am Canadian. I'm from Calgary and I went to the University of Toronto.

PW: There was a throne speech the other day. The government said that it wants Canada to become “the world’s leading hub for science and innovation.” Now, you've written a book about how a place becomes a global hub of science and technology. Do you think that's transferable to Canada?

McGee: You know, I get pessimistic about America's ability to scale like China's, and that's 10 times the population of Canada. So, I mean, gosh, you're asking a little Canadian here to sort of say something bad about Canada, because I'm not going to be all that optimistic.

I mean, we have to put in the old college try. We need to be participating in this. There are some facets of semiconductor fabrication that Canada has expertise in. I don't remember exactly what the specifics are. I believe it's in the quality assurance, the quality testing area. We have specific kinds of microscopes and stuff. There are niche things that you can get involved in. But Canada is never going to be the whole shebang in terms of, you know, rivaling China, and putting together really complex systems. But that's not to say that they can't participate in some niche facet where you develop a certain expertise and pour a lot of resources into it and excel on the world stage.

PW: Now let's get into the main event, which is your book, Apple in China. I think — a little bit like Jon Stewart — I was delighted to learn that it's not an essay or a polemic. It is a deeply reported book that gets 90 pages into the story before China makes its first appearance. And one of the big things you say is that nobody planned this. It was a series of unlikely events that led to China making Apple, and Apple making China.

McGee: In retrospect, it makes all kinds of sense. But nobody was seeing it at the time. The reason why it's 90 pages in is because I think we, in the media, failed to really do our job of covering Apple accurately as a manufacturing company. I mean, it might not manufacture things itself, but it used to. It used to have factories in California, Colorado, Singapore, and Ireland, and when it shifts to outsourcing, it's a 7-year experimentation stage before China emerges, in effect, as the winner. In 1999, no products are being made in China and by 2009 virtually all of them are.

But along the way, Apple was not just dabbling, but doing serious investment, serious production — in Wales, Mexico, Singapore, Taiwan, the Czech Republic, Korea. There's a tremendous period of experimentation before China wins out, and we just hadn't told that story. Find me another history of Apple that tells you about Foxconn in the Czech Republic. It just hadn't happened, and so I sort of needed to hand-hold the reader to understand Apple.

Apple was really the last holdout before adopting the offshoring, outsourcing model. And even when they do so, it's all new to them. And then China emerges as a country that doesn't have a lot of skill, but boy, do they have scale. And Cupertino has a lot of skill, they have no scale. And it's kind of a perfect marriage.

PW: Part of the story is that Apple didn't go straight to the lowest-wage jurisdiction. I mean, they go to Wales. They go to Mexico. It feels like in the early going, Apple's not even entirely sure what they're looking for.

McGee: Apple is distinct from the other computer makers, because what they chase is not cost. They chase quality. China’s offer is: we will do whatever is needed to win these orders. And so — because tech competence isn't what China offers in 2000, but ubiquitous, abundant, and affordable labour at factories being put up at such a scale that, if you were trying to do it in Ontario, we'd still be doing the environmental paperwork while the factory is up and running in China — Apple takes advantage of that in a way that nobody else does. Because there is no Jony Ive [chief designer of Apple products after 1998] at Dell or Gateway or Compaq. Apple is coming up with these maddeningly intricate designs. They are the sort of designs that could only be built on a conveyor-belt production system that they establish in China. Apple isn’t chasing the low cost, but the low cost is baked into the equation. You can only come up with these crazy designs if you have a place that's affordable to execute those designs.

China emerges as the one country that's willing to bend over backwards to make everything happen for Apple to come out with all these world-leading products. The problem is the negative externalities, to use the economic jargon. The problem is engendered in how Apple designs and then builds its products. It’s a form of technology transfer: because of their zero tolerance for defects, because of their maniacal obsessiveness with perfection, and then because of the quantity of products that they're building— we're literally talking about a half billion products made per year— the technology transfer embedded in building everything in China is on such an epic scale that a corporate history quickly becomes a geopolitical history.