The Q&A: "He was forthcoming and honest and funny and insightful — but damaged."

A new memoir dishes on late nights and high stakes in Pierre Trudeau's PMO

In the late 1970s, perhaps the second or third most powerful man in Ottawa was Jim Coutts, a baby-faced Alberta-born lawyer, not yet 40 when our story begins, and trusted, though not particularly beloved, by his boss, Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Coutts was Trudeau’s principal secretary — the guy you had to get through if you wanted to talk to Trudeau, the guy you had to persuade if you wanted him to talk to Trudeau.

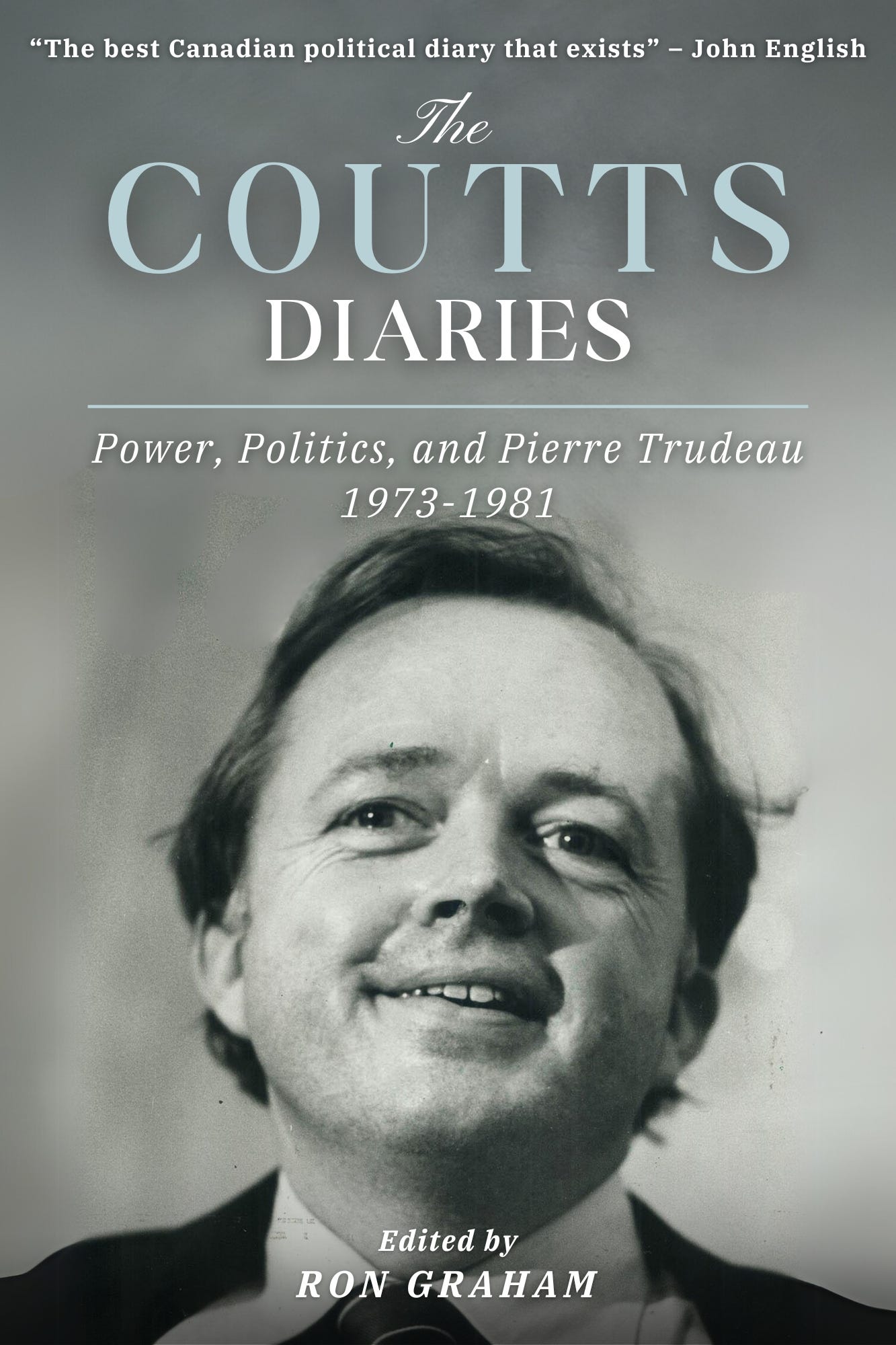

Coutts used to joke about keeping diaries that would spill all the backroom secrets of the day. Today, Sutherland House is publishing those diaries — The Coutts Diaries: Power, Politics and Pierre Trudeau, 1973-1981. It’s a gutsy move by Sutherland House, and as a guy who’s written for them, I confess I hope it pays off. The ’70s are prehistory to today’s readers — that’s even before my time — but prehistory had dinosaurs in it, and it’s fun reading how the damned things walked and ate. The back cover of this book features an enthusiastic blurb from me. It’s a fascinating extended look at the exercise of power by some highly eccentric personalities at a crucial moment in the country’s history. Both Coutts and his boss come off as thoughtful, dedicated and flawed. Among other things, you’ll be surprised how much poker there is in this book.

Ron Graham edited the Coutts diaries. A prominent magazine writer in the 1980s, he worked with Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chrétien on their memoirs. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Paul Wells: Why is there so much excitement about the publication— 50 years after the fact— of Jim Coutts's diaries?

Ron Graham: Well, I'm glad to hear that there actually is excitement outside my own! I had a lot of trouble finding a publisher, both academic and commercial, for this book. Luckily Sutherland House and Ken Whyte decided that it was almost a civic duty, even though they might be risking their shirts, to publish it. They went ahead to do a volume that was substantial enough to be worthy of the subject. And so, yes, there's some buzz.

I think it's a really important book for history. I think it's a masterclass for living, active politicians and political nerds.

PW: Let's fill in some of the blanks for people who aren't up on all their Jim Coutts trivia. Who was he? And what kind of figure did he cut in the Ottawa of the ’70s and early ’80s?

Graham: Jim was an interesting character, because he began very, very young in small-town Alberta, as a Liberal in a place and a time when you could look a hundred miles and not find another Liberal. He liked the party’s values. It was picking up a little bit of the John Kennedy stuff in the States. Coutts became an organizer. He got a job, very, very young, with Lester Pearson in Ottawa, when Pearson became Prime Minister. Then he went off to the Harvard Business School, got into business and was basically excluded from the early Pierre Trudeau government. Because when the Trudeau government came in, they pushed all the Pearson people out, and that included Jim Coutts and Keith Davey, who were instrumental in those elections of Pearson's. There was a disastrous election for Pierre Trudeau in 1972 where he went from a big majority to a minority, and almost lost. At that point he called back Coutts and Davey to help politicize his office and help him get back in the saddle.

Coutts ran the 1974 election, which did bring Trudeau back as a majority. That was the famous Margaret election. Coutts was instrumental in that victory, and then he became principal secretary to Trudeau in ‘76 and remained so until he left politics in ’81.

At that time between ’76 and ’81, he had the reputation of being the most powerful principal secretary in Canadian history. Everything went through him. He picked up all the files that Pierre Trudeau wasn't interested in or didn't care about, which turned out to be quite a lot. As the book reveals, he exercised power shamelessly in the name of the Prime Minister. He was Trudeau's principal political advisor, but he was also a policy wonk, as the book, I think surprisingly, demonstrates. He was into every major file, except, I would say, Quebec and the Constitution, which was the one area where he really wasn't an active player

.PW: I was in high school when Trudeau tried to get [Coutts] elected to Parliament by appointing an incumbent MP to the Senate to clear the way for a by-election. But then the people of Spadina riding decided they didn't want Jim Coutts to represent them in Parliament. Reading about that in Maclean's at the time, as a kid, I thought, So this is the power elite assuming that they know how things are going to go, and the people deciding they're not going to go along with it. That was one of the early signs of trouble for Pierre Trudeau.

Graham: Definitely. And it was a big surprise for Jim Coutts, particularly since it was considered a safe Liberal riding right up to that election, and he only lost by a few hundred votes. But nevertheless, it was a vote not only against Trudeau, which was real, but perhaps another candidate might have been able to carry that by-election. Coutts had become particularly vilified as the personification of the worst of Pierre Trudeau's government. The centralization of the PMO, the government by polls, the sleazy elections where you're toying with the public in order to put through some secret agenda. Every principal secretary becomes a lightning rod for people who hate the Prime Minister of the time. That was true before and it's been true ever since, but because of Coutts’s high profile, because of the number of enemies he made — both in Cabinet and the party — and because of his assumption that he knew politics well, it was a huge blow to him.

PW: Shortly before Pierre Trudeau leaves politics, Jim Coutts walks away from politics for the rest of his life. I know Liberals who would check in on him and chat with him, and who valued his experience, but he was out of politics from around 1982-on, it seems to me.

Graham: He ran again in ‘84 in the Spadina riding in the John Turner election and lost even bigger. But so did the [Liberal] party. Interestingly enough, his political diaries end the very day he leaves Ottawa to go and run in Spadina and he never really keeps a political diary again. After that his diaries are social, travel, almost glorified scrapbooks and photo albums.

All the way through the diaries, he's warned about his reputation. He knows that his reputation is bad. He knows there are people with their knives out for him, but he sort of says this comes with a territory. There were rumors that he was going to run for leader. He knew he wasn't going to win more than 15% in a leadership campaign, so he knew that he was vulnerable. But nevertheless he thought because of the polls, and because of his cockiness and also his savvy, that he could win this [Spadina] thing, and he was crushed.

PW: Now, a million years later, out comes this book, thanks to you. What's the significance of Coutts's diaries? He would refer to them from time to time. At the time he would say, “I'm making a list and checking it twice,” sort of thing.

Graham: Yeah, he made a joke about them in the sense that he would say, Oh, that'll be in my diary, or You better watch out — that’s in my diary, always in a mischievous way. People knew about these diaries, but nobody had really read them. I think a couple of people read a couple of pages from time to time. There's one sequence where Trudeau asked to see a couple of pages about the Turner resignation, but basically nobody knew what was in them. [Coutts] had a great sense of humor, and to some extent one of the weaknesses of the book is that it doesn't reflect his humor as much as being in his company. He was a great raconteur, he was fun, and the diaries are more serious. Even though it's a lot of personal stuff, he's really trying to record history and the important stuff.

It's a fairly serious book, but I remember at one point I was at a dinner and Brian Mulroney, famously, got up and sang When Irish Eyes Are Smiling or something, and Coutts walked by, and I said “Hey, Jim, when are you going to sing?” And he said, “When I sing, all these people go to jail”.

So, the diaries were known, but nobody knew what their quality was — whether there were gaps, whether they were interesting, whether they were well-written, whether they were full sentences, or just notes. Nobody knew.

When I found out the diaries were going to go public in January 2025, I asked the executor if I could get a preview in order to see if there was anything in there that might be publishable, and of interest to the modern world. The content that I found was actually surprising to me in terms of how thorough it was, how well-written; the dialogue, the hour-by-hour, the conversations, the frankness, and the personalities I often found were very fair. [Coutts] had a reputation of being mean, and he could be at times, particularly when he was drinking. But the characterizations of people are pretty accurate. Most particularly Pierre Trudeau, who becomes a complex and fascinating figure even more than we knew.

That's the value of the diaries— they really are an exceptional inside record of those years, and those were important years because they included the Constitution patriation, national energy policy, and 4 major elections. They are a unique record of our history. Mackenzie King wrote, of course, famous diaries at length. [Coutts’s] are more readable and less detailed, more frankly observed, I think. Charles Ritchie, of course, was a gifted diarist, but he wasn't at the center of the action like Coutts. You have to go to England, where political diaries are an industry, where every backbencher seems to write a 16-volume biography of everything, including their love-life. And they sell. We have no tradition like that. And that's one of the reasons why the publisher is a little worried about whether there's a market in Canada for this.

PW: This is a young man in his early thirties when the story begins. He’s not intimately trusted by the Prime Minister, not at first. And as a matter of fact, he'd been shunned by the Prime Minister and brought back, to some extent, over Pierre Trudeau's dead body. It’s at the dawn of a crucial period in Canadian history. The story begins shortly before the Parti Québécois gets elected in Québec and it goes through two of Trudeau's last elections, the Referendum, how the hell to deal with a global energy crisis in the context of Alberta's resource wealth.

I'll give you a couple of my impressions, maybe give you something to bounce off of. It's sort of the informal economy of Ottawa in the 1970s, in that it's a hell of a lot of lunches and breakfast meetings and chats on airplanes and stuff like that. The workday, as such, is less prominent than I thought, and it's more: Then I went off to have lunch with Keith Davey, or Then I had breakfast with Michael Pitfield, and it suggests that a lot of what was transacted was a long series of informal conversations among a tight-knit circle of power. Am I close to getting it right?

Graham: Yes, I think that's right. Obviously, by the time these debates and decisions come up to the level of the PMO, a lot of hours and work have gone into getting it that high. You're seeing the top of an iceberg in terms of decision making. These informal conversations, these lunches, these meetings, are just the tip of them going over the thorniest, most difficult problems. Sometimes that's in a formal meeting with the Prime Minister and his famous “gang of five”, and sometimes it's schmoozing over lunches and things.

At Cabinet meetings, Coutts would go to the back of the room and park himself next to the coffee machine. During the course of that hour or two of standing there, every minister would float over and say, Jim, I need this. What about this? What about that? What about here? I'm blocked here. So-and-so is here. What's that going on? And [Coutts] would accomplish a week's work, just by five minutes with each minister at the coffee machine. That's the type of informal thing that I think you're talking about.

PW: And then there's an element of this that's even more informal than that. Which is that this guy was playing poker a couple nights a week. At very high stakes. And staying up very late — while he was helping Pierre Trudeau to run the country. There's a kind of offhand reference to one night when he went to the Rideau Club and played poker until 2 a.m., lost $2,400 — in the early 1980s, when that was real money. That's the side of it that I was amazed to read about.

Graham: I was amazed to read about that, too. He wasn't a poker player when I knew him, but he was a heavier drinker. There was a lot of drinking and a lot of smoking cigarettes, I hasten to add, and he's always trying to give up all three of those things. But the poker was the one that really seemed to be the addiction. Sometimes he was playing three or four times a week. And as you say, sometimes those games went on, not just till 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. Sometimes they went on till 11:00 the next morning.

And then he would describe going to a meeting, and he'd kick himself by saying, I'm too old to do this, and I shouldn’t have done that. This was a really important meeting. I'll just go and have a nap. I'll tell the Prime Minister's Office that I've got a meeting, and I'll come in in an hour, and I'll go have a sleep for an hour on the couch.

One of the most dramatic chapters is when Trudeau resigns and is then convinced to come back in December of 1979, out of retirement, when the leadership race has already begun. That chapter is pure, raw Jim Coutts at his very best, because basically, Trudeau woke up the morning of the press conference and said, “I'm not going to run.” Coutts says, “Wait a second, I'm coming over in a taxi to Stornoway.” They sit down for an hour, and Coutts outlines in his diaries exactly what that conversation was like. [Trudeau would not have returned from retirement] if Jim Coutts hadn't had that conversation with Pierre Trudeau.

PW: That last Trudeau term is basically the one that includes everything we learn on the first day of learning about Pierre Trudeau. That's the referendum. That's the National Energy Program. And that's repatriation of the Constitution.

Graham: It's interesting because the biographies of Trudeau have this gap, sort of around 1970. He wins in ’74, comes back with his majority, and he basically does nothing. It was a tough time. It was stagflation, inflation, oil prices, the PQ, Alberta acting up, Margaret and the divorce. It's clear that Pierre Trudeau didn't have his act together for about 3 or 4 years and just run out of steam. He was distracted. Which meant that Coutts and Pitfield were running the government, more than we even suspected, on the major files of that period. They were trying to get an industrial policy going, trying to save the Auto Pact, trying to figure out oil prices, trying to deal with the United States. The Prime Minister was sort of checked out — except, maybe, for the Constitution. It's remarkable evidence of what was suspected at the time: that that party and the Prime Minister had run out of steam in those times, and deserved to fall in ‘79.

PW: Who is the Pierre Trudeau that we see in this book?

Graham: It's confirmed here in detail that he was a brilliant, focused, extraordinary Canadian with a vision for the country on national unity, multiculturalism, and the Charter of Rights. After that there was a man who was caught in a role that he was surprised to find himself in. In ’68 it was Trudeaumania, the hero of the nation, and then by ‘72, people were disillusioned with that because they felt he was arrogant and difficult, and not respectful of them. All of those negatives started to attach to him, and they followed him through the polls all through the ‘70s. Coutts made suggestions and Trudeau basically confirmed the polls by saying, No, I'm not going to do any of that. I hate the media. I'm not going to speak to them. I hate Bay Street. I'm not going to speak to them. [Trudeau’s] being inattentive and telling Coutts to deal with things. He tells Coutts: Inflation is your agenda. You know I don't care. I don't care about the Canada Development Corporation. You go to do something about it.

Trudeau emerges as a human being. They all emerge as the human beings. Because of the diaries, you see them being neurotic, difficult, obsessed, with marriage problems, alcohol problems, turf wars, petty problems. It's a swirl of very complex, slightly weird individuals trapped in this national agenda of historic importance mostly with Pierre Trudeau at the core of it. It's an astonishing revelation of how complex— both on the negative and positive sides— [Trudeau] was.

PW: There’s one other thing that I wanted to talk about, which is the change in the journalistic environment from Pierre Trudeau's time to our time. Your first book, One-eyed Kings, is on my list of ten books that I recommend to everyone. It is a succession of 6- or 7,000-word portraits of the main players of the day: John Turner, Joe Clark, Brian Mulroney, Pierre Trudeau,. Each of those chapters began life as a long magazine profile of the kind that were common in those days and have essentially vanished. What's been lost in the environment of political journalism?

Graham: Well, it gets back to the issue of what's the fate of this book [The Coutts Diaries]? There’s been a total collapse of the Canadian newspaper and magazine publishing businesses. There are many guilty suspects out there, but we all sort of know what's happened. One thing is that there's just not the vehicle. I mean, when I was doing those Saturday Night articles, I was allowed to spend 3 or 4 months following Joe Clark around the country during an election, with expenses. Now, sometimes I had to sleep on a friend's couch, but they were pretty good. They gave me the length to write about them.

The pay was always crummy, but it's even worse now. In fact, I think it's the same dollar per word as it was in 1970. Then you get into all kinds of issues with attentive readers. Who's buying a book anyway, these days? Then you get into the much more complicated— and I think more important— public policy issue of our shameless abandoning of the nonfiction and historical side of our country. Our publishing industry is foreign-owned, our newspapers are broke, our magazines are charities effectively. The best and brightest—and you're one of the few exceptions to this rule—go off to earn their money somewhere else by becoming lobbyists, or think-tank people or government bureaucrats, because they can't make a life out of this trade. It's a complicated issue.

PW: This is one of the things, and I don't talk about it much because there's almost no point talking about it in journalistic circles. But every time an election comes around, I think: when is somebody just going to absolutely go to town on the circle of people around Pierre Poillievre, the circle of people around Justin Trudeau, the open secret that Mark Carney had people campaigning for him to become leader of the Liberal party for years before he announced himself as a candidate. Soup to nuts. The whole crazy drama of it. And it is so difficult for most working journalists to even begin to scrape together the resources to tell that story. It doesn't even occur to most people that that's a kind of story that you can tell. We've got more access to more sources of information and communication than ever before, and the whole story seems impoverished compared to what it used to be.

Graham: I think it is. It's not like this in every society. I mean, if you look at the Americans, you certainly know who every Secretary is, and you know everything about the President. And here, cabinet ministers come and go, and nobody really knows anything about them, even people who follow it. You get a little bit of Wikipedia sort of info, and a little bit of this, and a little bit of that. Every now and then there's an attempt. I'm guessing at this point that decision-makers like these publishers are saying, Nobody's actually interested in this. They want a scandal, or some gossip, or somebody's taken an airplane ride that they shouldn't have. I don't blame the reporters because I don't think they have the time to do that type of reporting. It's a shame. But I think it's part of a national malaise where our history and nonfiction have been hung out to dry.

PW: I am curious to see how this book does. What I've been saying to friends is, it turns out that 50-year-old gossip is almost as good as fresh gossip and this book is jam-packed with 50-year-old gossip.

What I recall about the Trudeau years (I was born in 1957) is just how bad they were. With our natural resources, we should have been one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Instead, we had years of economic lethargy. Both he and his son were terrible leaders who did irreparable damage to Canada. I also recall how lionized Pierre was in the mainstream press and the CBC. Prior to Pierre, we did not have Western alienation and Quebec separatism.

Thanks Paul for this interview. You helped sell a copy of this book. Looking forward to reading it.