Tony Bennett died on Friday at 96. In 1990, when I first saw him perform at the Festival International de Jazz de Montréal, I was not yet 24 and I had no idea how much I didn’t know. My review from that concert for The Gazette was so snotty I’ll spare you excerpts. Old guy in a suit, what does he know, was the general attitude. He was seven years older than I am today.

A year later, correction arrived in the mail. In those days record companies would send boxes of CDs to large newspapers; I had swindled my way into a half-time side gig as the paper’s jazz writer on top of my news-writing duties, and the Bennett compilation Forty Years: The Artistry of Tony Bennett landed on my desk. In some ways, Bennett was easier to appreciate if you could only hear him. Stripped of patter and routine honed in a thousand concert halls, what remained was an extraordinary voice and a seriousness that defeated skepticism.

That compilation ended with a song from what was then Bennett’s latest album, Astoria: Portrait of the Artist. “When Do The Bells Ring For Me” is an oddity, a single chorus, three minutes of crescendo, written by a not particularly illustrious Manhattan cabaret singer named Charles DeForest. To me it’s a nearly perfect song.

In 1997 Bennett was back singing at Place des Arts. He was on the back foot; his regular drummer, Clayton Cameron, was unable to make the gig, so Bennett had called Lewis Nash, a superb jazz drummer, to sub in. They spent the night watching each other, Bennett feeding cues, conducting with a glance or a shrug, Nash catching and orchestrating the hints. The interplay between them made it obvious how much musical skill Bennett had, chops and insight beyond what the road usually required.

At the end of the night Bennett called up a young singer from Nanaimo, a terribly nervous 32-year-old Diana Krall, who sat at the piano while he held a microphone for her. They sang a duet on “They Can’t Take That Away From Me.” “The way your smile just beams,” Krall sang, staring into his eyes, “The way you sing —” She caught herself. “You don’t sing off-key.” They would perform together many more times, as would Bennett with kd lang and Lady Gaga. To me, Bennett’s endorsement of another singer was dispositive: if he thought she deserved his company, that settled a debate, if any room for debate still remained.

I interviewed him once by phone. We talked about art — he was an enthusiastic hobby painter, usually views from his hotel rooms in oils. I mentioned I’d be talking next to Jim Hall, the wonderful jazz guitarist. Bennett shifted gears from amiable to excited. “You’re going to talk to Jim Hall? Could you please say hello to him from me? Tell him I’d really like to play with him.”

In jazz and American popular song, a “standard” is a song that was, usually written for a Broadway show or movie and has become part of the music’s shared vocabulary. Bennett mostly sang standards, of course – ‘I Get a Kick Out of You,” “Sing You Sinners,” “Lullaby of Broadway,” “But Beautiful.”

Of course the word has another meaning. Standards are the expectations a serious person brings to their work. Bennett was in and out of fashion but he stayed in style because he had high standards to the material he chose, the musicians he worked with, and the way they approached their work. As he moved further from Astoria into the world, his work reflected more clearly the influence of the finest jazz musicians — Billie Holiday, Art Tatum, Count Basie. You could hear Holiday in the way he bent vowel sounds especially.

I last saw him in New Orleans in 2009. He was in superb form, better than the time before. His longtime pianist Ralph Sharon had retired, to be replaced by an efficient but rhythmically boxy cabaret pianist, but Harold Jones, a veteran of the Count Basie band, was in on drums at the age of 69. As if Bennett was determined that by God, somebody in this band would know how to swing.

I loved him very much. Here are five albums that make it very clear how serious Tony Bennett was about his standards.

Cloud 7, 1955.

Bennett was five years into a career as a hitmaker when he released his first full-length album in 1955. A surprisingly understated and coherent affair, as though he was already sure enough of more hits that he could afford to pursue less sensational effects. On ballads and mid-tempo swingers, Bennett, still in his 20s, is still green, but the album wears better than much of his ‘50s output.

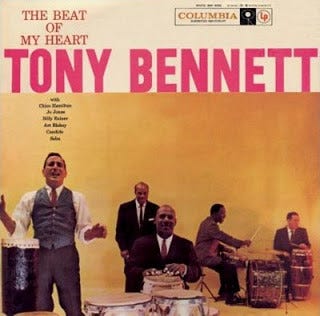

The Beat of My Heart, 1957.

An astonishing album. Bennett and his new pianist, a low-key but encyclopedic Brit named Ralph Sharon, decided to build an album around the finest jazz drummers. Once again it’s hard to imagine a less commercially-motivated move. Enter Art Blakey, “Papa” Jo Jones, Candido and others on what amounts to an album-length manifesto on the drum’s role in American music. What’s more: Bennett was clearly using his privileged position at the top of the hit parade to get himself close to musicians who could school him in performance practice. One way to last is to remind yourself you’re still a student, long after people have started to treat you like a big deal.

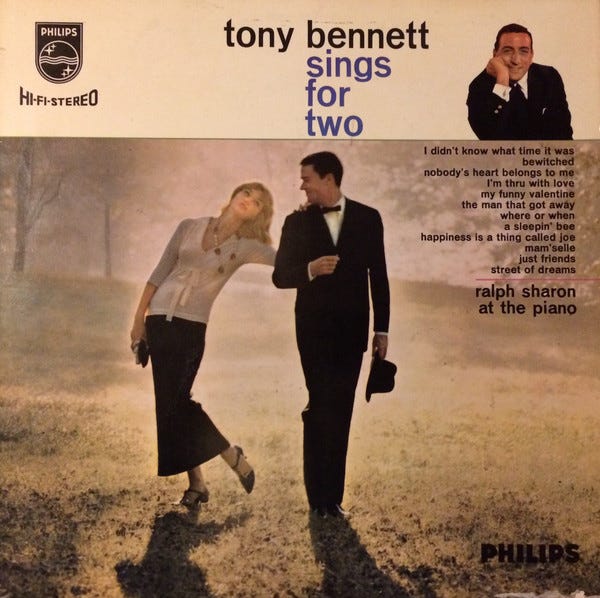

Sings for Two, 1961.

Fourteen years after this duet session with Ralph Sharon, Bennett would release the first of two duet albums with Bill Evans, incontestably a more significant pianist than Sharon. Everyone else will recommend The Tony Bennett/ Bill Evans Album and Together Again to you, and you should absolutely check them out. But I keep coming back to this earlier album, on which Bennett and his longest-serving musical partner deepen their interplay. Sharon nails the tempos down with watchmaker precision, solos briefly with fine ear for melody, and rolls out the red carpet for the boss.

At Carnegie Hall — The Complete Concert, 1962

Pluperfect young Bennett, in a great hall with a belting big band, performing the set list that would be the basis for his work for the rest of his life. Yes, including “I Left My Heart In San Francisco.” This concert was recorded 10 days before his studio performance of that song was released. It would be his biggest hit. Columbia slammed this album out, getting it to market only a month after the concert, an unbelievable hurry that reflected the kind of sales potential they knew they had on their hands. The whole thing is self-recommending, but listen to “Lost In The Stars” to hear the depth of feeling Bennett could command.

The Silver Lining: The Songs of Jerome Kern, 2015

His last great album, with the trio led by pianist Bill Charlap, with whom Bennett had been performing occasionally since the 1990s. Again, as always by this point, that Billie Holiday glow. “I’m old fashioned/ I love the moonlight,” Bennett sings over Peter Washington’s walking bass, tying the “o” in “love” into a bow, like a gift to Billie. Nobody has a silvery touch on piano like Charlap. A summit meeting, a summation, a challenge and pep talk to anyone else who will ever try to perform these standards to these standards. Here’s a video from around this time. The way he sings, “I love you.” My God.

Nice piece. I photographed Tony Bennett for my friend Whitney Balliett at the Place des Arts in Montreal in the 70´s. It was for a book that became Alec Wilder and His Friends. During the intermission I was summoned to Bennett’s dressing room where he told that his shirt was showing through his tuxedo and no photographs could show this. I’m afraid I ignored him

He led a long and gifted life it but a great loss none the less. Not many originals left who still sing the American songbook. Attended a disappointing Diana Krall show Le Festival International de Jazz this year and lamented Bennett’s steady hand on her performances thereof... Another great bit of writing Paul. Remember fondly the work we did together bringing jazz to ears of Montréalais back in the day.