In Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s 2019 novel Fleishman Is In Trouble, which will soon be a miniseries starring Jesse Eisenberg and Claire Danes, most of the novel is about Toby Fleishman, a young physician, reeling after his estranged wife Rachel drops their children off at his place and vanishes. The kids cramp his style as a born-again single! It’s unfair!

Only in the book’s home stretch do we find out what’s been happening to Rachel.

At the Public Order Emergency Commission on Wellington Street, everyone has been talking about Peter Sloly for two weeks. Senior members of his command marvel at the way he micromanaged. Federal and provincial police, hovering at the edges of the siege, wonder why Sloly didn’t call them in. Brenda Lucki and Thomas Carrique, commissioners of the RCMP and the Ontario Provincial Police, share a few LOLs by text message. Lucki tells Carrique the feds had lost faith in Sloly by Feb. 5, the second weekend of the mess. Outgunned, outmanned, outnumbered, outplanned.

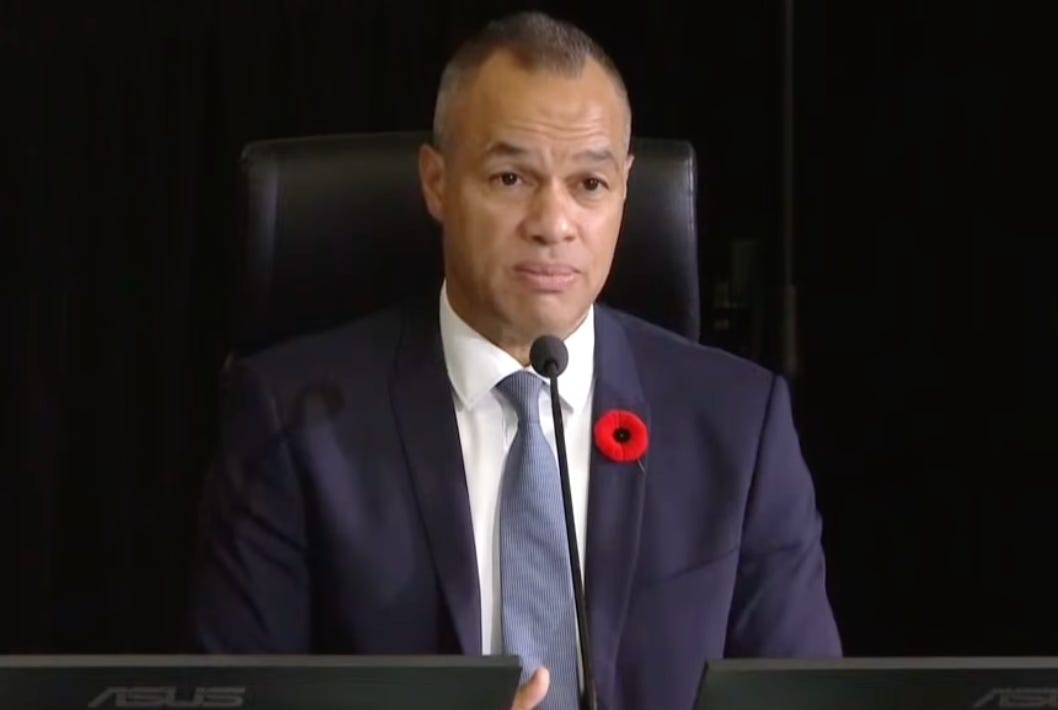

And now here was Peter Sloly himself.

I liked him.

The former Chief of the Ottawa Police Service was born in Kingston, Jamaica two weeks after I was born in 1966. His CV, which was posted to the commission website, carries the motto “Others before self, compassion for all.” In his late teens and early 20s he played professional soccer in Toronto. He still has an athlete’s poise. He lists eight higher-education institutions he attended, from St. Francis Xavier University to the FBI Academy at Quantico, Virginia. For 18 years he worked his way up in the Toronto Police Service, ending in 2016 as Deputy Chief. He had a senior role at Deloitte, the blue-chip consultancy, for a time after 2016. Since he resigned on Feb. 15, he’s been a “Visiting Fellow and Change-Maker-in-Residence” at Massey College, which retains its venerable role as a soft place to land for Canadian leaders who find themselves low on luck.

Sloly doesn’t appear to have worked in Ottawa before 2019. In testimony on Friday, he briefly had to reflect on which lane of Wellington Street he had tried hardest to keep clear in the early stages of the convoy occupation. “I always get this confused,” he said. He settled on the south lane. This is a common stumbling block for outsiders. Toronto and Montreal were built northward from their waterfronts (not really, in Montreal’s case, but Montrealers use “north” to designate an odd sideways direction that can’t be drawn on traditional maps). Ottawa’s Centretown extends south from the Ottawa River. The city feels upside down if you didn’t grow up here. That feeling never really goes away.

Sloly is poised, earnest and a better talker than almost anyone who has testified so far to Commissioner Paul Rouleau. He was careful to open any discussion of any colleague with praise. (The discussion normally got more complicated later.) He frequently paused his testimony so official-language interpreters could catch up. He wore a poppy in his lapel, which got me wondering. I learn that the Royal Canadian Legion advises Canadians to start wearing a poppy on the last Friday in October. Which this was.

It was a day later before I managed to put my finger on another incongruity. Sloly was the first witness in several days who wasn’t wearing a dress uniform. It’s because he is no longer a cop.

One more thing became progressively more apparent as Friday wore on: Sloly comes from outside the Ottawa Police Service and the community it serves. His lieutenants during the mess, Patricia Ferguson and Steve Bell, each have 30 years of policing experience in Ottawa. Bell had applied for the chief’s job and been passed over in favour of this guy, who still doesn’t pronounce “Rideau” like a local.

Whatever else went on in the three weeks between the convoy’s approach in late January and Sloly’s resignation on Feb. 15, clearly there were elements of a culture clash. An outsider directing insiders. Book-smart meets street-smart. Much of their mutual incomprehension persists.

Sloly spent an extraordinary amount of his time the witness stand explaining things that should no longer need explaining. Things like whether plans he discussed on successive days were different plans or the same one. Or why Sloly would sometimes speak directly to officers at junior levels in the force’s hierarchy, rather than waiting for reports from the chain of command. Or where he stood on questions of enforcement, on a spectrum from lenient to punitive.

The force, as his former colleagues have already testified, was worn down to nubs before he arrived — by COVID, Black Lives Matter, defund-the-police, and waves of turnover in his senior staff. Then successive lockdowns and work-from-home arrangements made it impossible to get to know his new charges well.

“So much is lost on Zoom,” he said. “Emails and text messages never cover it. Even when we could get together we were masked up. So we could never really see each other.” Perhaps I’m the only person who would hear that and think of Erin O’Toole, whose entire tenure as leader of the Conservative Party of Canada took place behind masks and at a distance.

Of course, O’Toole had other problems too. Plainly so did Sloly. I found him an engaging figure, I’m glad the people at Massey College can benefit from his experience, but I take Thursday’s testimony from OPP commissioner Thomas Carrique as a bit of a tie-breaker. Carrique spent weeks waiting for Sloly to make a coherent request for defined assistance, and wondering why Sloly was publicly calling for reinforcements whose roles he had made no effort to explain directly to the OPP.

As Sloly said himself, by the time he resigned on Feb. 15, he had “little to no support from elements at [any of the] three levels” of responsible policing — his own force, the OPP or the RCMP. When everyone’s mad at you, Occam’s razor suggests you might be the problem, or at least contributing to the problem.

Commission counsel Frank Au doesn’t really switch up his game plan from witness to witness. He starts by asking about the weeks before the convoy hit Wellington St., and is barely past the first weekend when it’s time to break for lunch at 1. Sloly’s convoy began the way almost every witness’s did: he was blindsided when a “weekend event” turned into a massive challenge to the public order.

There’s no point rehashing much of this. Many of the advance intelligence reports — especially the OPP’s prized Hendon reports, which I now hear as “the Glengarry leads” — contained lines that read, from the battle-weary present, like neon-bright warnings: the convoy would be huge. It had no plan to leave.

But the Ottawa police see protests all the time, including sometimes with heavy rolling equipment. Those protests had always left. Muscle memory told the OPS this would be fine. Sloly said he “skimmed” the odd Hendon report, and mostly passed them off to his deputy chiefs, one of whom, Patricia Ferguson, has already said the convoy taught her to start reading Hendon reports.

Nearly 20 years ago, after a much bigger catastrophe that not enough people saw coming, Malcolm Gladwell wrote, channeling Yogi Berra, that it’s harder to predict something before it happens than after. “What is clear in hindsight is rarely clear before the fact,” he wrote, and maybe we can take that as permission to cut all of these people a little slack.

Sloly asked for more than that. At the end of a long day on the stand he was asked what he could have done differently. More sleep might have helped, he ventured. That’s probably not going to satisfy a lot of Ottawans.

He said it took two hours on the first Saturday, Jan. 29, to realize the OPS’s tidy preliminary arrangements with the truckers, this business of parking at distant parks and riding shuttle buses to Parliament Hill, had collapsed. The convoy from Windsor had made it to Wellington Street ahead of everyone, and absolutely every other visiting protester wanted a piece of that action. Chaos ensued.

It was at this point that Frank Au asked Sloly what he thought of the OPS’s reaction as the city sank into entropy. This is the point where Sloly paused, admitted he found fielding such questions “tricky,” and started to cry. You’ve seen the clip if you watch TV.

“It was too cold and it was too much,” Sloly said. “But they did their very best. And I'm grateful to them. They should be celebrated. Not celebrated, it's the wrong word. They should be understood.”

Au: “Do you feel that they were misunderstood? Can you elaborate on that?”

Sloly: “The level of disinformation and misinformation was off the charts. It was crushing to the members’ morale. Crushing to the incident command team's morale. It was crushing to my executive team's morale. I suspect it was crushing to the [Ottawa Police Services Board]. It was crushing to everybody. It was unrelenting, It was 24 hours a day. And I think by the end of the weekend, it had become a global story that mainstream media was following. And none of it was portraying, in any way accurately, the hard work of the men and women of the Ottawa Police Service and the partner agencies that stood with us. None of it to this day has.”

I’ve been analytical here on other days and will again, so maybe you’ll forgive me if I just let Peter Sloly talk some more. It’s pretty clear he won’t get the last word in this matter. Next week’s witnesses will mostly be members of the convoy. Others will follow later, including the prime minister of Canada.

Meanwhile Frank Au wanted Sloly to explain a meeting at 8 a.m. on Saturday, Feb. 5, that Trish Ferguson discussed at length in her testimony as a case of Sloly inventing new plans on the fly and micromanaging down to levels no chief should bother with. By coincidence, Feb. 5 happens to be the day Brenda Lucki told Thomas Carrique by text message that the government of Canada had given up on Peter Sloly.

For Sloly, that Saturday began at 3 a.m. “I woke up, because I wasn't getting a whole lot of sleep those days. I woke up somewhere around 3 o'clock in the morning. Could not get back to sleep.

“I checked the situation report that came in from the duty inspector, Frank D’Aoust… The Confederation Park negotiations had ended badly. The Indigenous elders that had come in were treated badly. There was an attack on one of our sergeants at one of the sites. Other city workers were being attacked.

“This for me was an alarming situation report in the middle of the night that no one else was likely reading,” Sloly said. “So I got in a shower, I got into my car and I got down to the station and I changed into my gear.

“And I looked around. We were thinly staffed. I understand why — there was not much to staff with — but we were thinly staffed. And when I went down onto what we call the Zero Level of our headquarters and asked the watch commanders there, and the sergeants, ‘What's our staffing levels look like for 9 o'clock, 10 o'clock, 11 o'clock when the bulk of the convoys are coming in?’, the numbers I got were really concerning….

“So overnight, we had an escalated level of threat at multiple different sites. And in the morning, I wasn't getting a sense that we had the staffing commensurate to what we had announced and what we actually needed. And so I needed to make sure that I could pull together an incident command team and ask these operational-level questions — to be assured that we were in a better state of affairs than what I was getting at that point in the morning.”

So he called the meeting, and nobody in the meeting could quite understand what the hell he was asking them to do. Several days later Diane Deans, the chair of Ottawa’s Police Services Board, asked him as casually as she could, kind of en passant, whether he’d ever thought about quitting. Whatever his shortcomings, it turns out he could take a hint.

At the end of Sloly’s opening testimony, Frank Au handed him off to counsel for other parties for cross-examination. But first, Au asked Sloly about that motto at the top of his CV. “Others before self, compassion for all.” What was that about?

Peter Sloly paused again. “It’s just how I was raised,” he said at last. “It’s who I am. Everything after that is just what I did.”

Comment board is open again. Try to be nice to one another.

I appreciated the tone of this piece. It reminds us that the participants in charge of the police work in Ottawa are humans, c/w all their frailties and character flaws and pressures to make good decisions on the fly.

Good decision making is often accompanied by a measure of good luck. Chief Sloly would have been a genius (not that he would have been credited for it) had the Convoy packed up and left within a few days. Because fate headed in the opposite direction, Sloly wears the goat horns instead.

Louis L’Amour would call Chief Sloly a rank outsider, parachuted into a plum job ahead of two 30 year veterans. Perhaps that is the real tragedy, a well meaning and dedicated police officer who never gained the trust of underlings or his civilian masters. When everyone is mad at you before a crisis strikes, that becomes a problem.