Overture and cadenza

Lots of people know Rik Emmett better than I do, but in case you’re not one of them, I should probably set the table for today’s story by showing you what he used to do at the peak of his commercial success.

Those were the days when Emmett was the guitarist and lead singer for the Toronto hard-rock trio Triumph. Here’s Emmett a few days before he turned 30, playing his trademark guitar solo on the tune “Rock & Roll Machine” at the US Festival outside Los Angeles in 1983:

What can you say about a performance like that? Maybe that Emmett was a hell of a guitarist and an epic ham; that a lot of people were delighted to hear him play; and that for years before and after that show, Triumph was performing on dozens of nights a year for crowds whose size would routinely run to tens of thousands. Sometimes they’d share bills with Foghat, Mountain or Molly Hatchet. More often they’d draw those crowds on the strength of their name alone.

Triumph had 18 gold and nine platinum albums in Canada and the United States. They’re on Canada’s Walk of Fame. There have been more successful bands, though not many. There have been more illustrious guitarists, though not a lot with Emmett’s flare for theatrics. But Emmett and his bandmates had a great run.

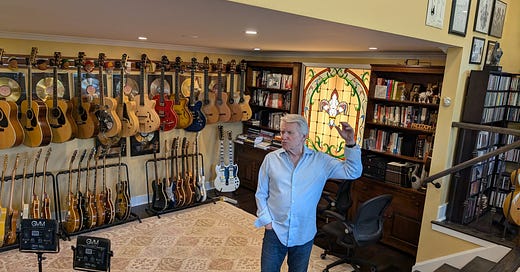

That was a long time ago. But Rik Emmett is still playing. Here he is the other day in his attic studio in Burlington, ON, playing a tune called “Swirling” for me and, by extension, for you.

In many ways he’s a better guitarist now than he was in stadiums. At 71 he’s appealingly comfortable with himself and the instrument that allowed him to make his way in the world. Well, with the class of instruments: I counted nearly 40 guitars in his studio. The collection used to be much larger. Guitarists like guitars, what can you do.

“I’m five foot eight and shrinking,” he told me. Arthritis slows but doesn’t stop his fingers. He loves telling stories about the road. He told me a couple, about a wonderful jazz guitarist and a band from Scotland, that I won’t repeat here. He’s retired after many years teaching the music business at Humber College. It’s six years since he stopped his manager from soliciting concert gigs, although he can still be coaxed onstage on a case-by-case basis.

I visited Emmett because in March he released an album called Ten Telecaster Tales. He also released a book called Ten Telecaster Tales, which amounts to 200 pages of liner notes for the album. I have taken a very belated personal interest in the Fender Telecaster guitar, one of the most legendary families of electric guitar in the history of music. A sidearm favoured by Springsteen, Keith Richards and countless others. So I had questions for Emmett. As soon as we got this federal election behind us, I headed to Burlington to talk to him.

Eli’s loft

Rik Emmett’s house is a block or two further from the surprisingly gorgeous Lake Ontario waterfront than the fanciest houses in Burlington, but when his wife Jeanette wanted an extension on the back, she encouraged him to build whatever he wanted on the next floor up. Of course he wanted a studio. He calls it Eli’s Loft. Eli is the merry-go-round horse that hangs on one wall.

“He wasn't originally Eli. He's a carousel horse that used to hang in our old house in Mississauga,” Emmett explained. “And then one day I was looking at him, and I went, ‘No, you know, Elijah was the prophet in the Old Testament. He’s the only guy that got to go to heaven when he was still alive. According to the story, he got in a golden chariot that was on fire, and off he went.’”

This was artist logic, which as everyone knows, helps less if it gets too logical. This horse was his company for his creative work, which is kind of like a golden fiery chariot, at least on a good day. So the horse became Eli the Wonder Horse, short for Elijah.

As a practical matter, Eli’s contribution to Emmett’s continued success is modest. “I sit here alone by myself, working away. And every now and then I look up and I go, ‘What the fuck should I do?’ …He just kind of looks at me, laughing at me. ‘You figure it out on your own.’ That's how it works.’”

A similar process led him to call his newest guitar Babs. The name is partly an acronym for “butterscotch and black” — the colours of the custom instrument’s wood stain and its black plastic pick guard, which protects the wood from flying guitar picks or fingernails. It’s also partly a tribute to Barbra Streisand, who has also sometimes been like a fiery chariot.

Babs is not, strictly speaking, a Telecaster, because it was not manufactured by the Fender Musical Instruments Corporation of Los Angeles, CA. But one of the things that surprised me when I started studying the history of electric guitars, six months ago, was that companies’ ability to trademark or patent the shapes of their instrument lines seems limited. So just about anyone can make a guitar that looks like a Tele, and even drop big hints that it’s a lot like a Tele — typically by marketing it as a “T-Style” guitar, hint hint — and the Fender Musical Instruments Corporation will, apparently, not send lawyers.

Babs is a custom job, built to Emmett’s specs. It started with hand-wound pickups built by Mike “Smitty” Smyth of MJS Custom Pickups in Mississauga. “Pickups” sit under a guitarist’s picking hand and translate the vibration of metal strings into electric current that will drive amplifiers. Smitty makes good pickups, apparently.

The rest of the guitar — swamp ash body with hollow chambers inside for lightness, maple neck — was built by Garren Dakessian of Loucin Guitars in Oakville, who makes guitars for a bunch of prominent guitarists..

Babs is light, but when Emmett sits with the guitar on his thigh, which is how he usually plays these days, the strings are at a height he likes. If his guitar had looked like a Les Paul — one of the other legendary families in rock guitar and the model he used in the 1983 video above [UPDATE: Swing and a miss, Wells. See the discussion of Les Paul-like guitars in the comments below] — the strings would sit a little lower. Less intuitive.

The early Telecasters were blunt machines, easy to manufacture, easy to service. Their modern descendents keep some of that directness. I’ve heard them called “wood with a piece of wood.” They’re almost inexplicably versatile, workhorses for blues, rock, country and jazz artists alike. They faithfully transmit to the amp whatever their owner’s hands do. Sometimes almost too faithfully, letting the world hear your weaknesses, like truth serum with strings.

Emmett’s custom guitar is carved with more eye for detail, and it’s a bit of a hybrid — the neck’s shorter then on a Fender, so it’s like Les Paul length at Tele height. Staccato notes from Babs don’t bark or twang in the way that makes Telecasters popular among country musicians, who sometimes call the effect “chicken pickin’”. It’s mellower, like its owner.

“When I'm getting older and deciding I want to try to combine fingerstyle, jazz, classical, flamenco — I want one guitar. I want a holy grail. One guitar to rule them all.” He intones this last bit, gives it a Lord of the Rings topspin. Re-reading his book later, I see he was quoting himself.

What does he play on Babs? This and that. One of the first pieces was a commission. A documentary filmmaker had set a film about in-line skates to a kind of gallumphing quasi-classical tune called “Bourrée,” recorded in 1969 by Jethro Tull. But copyright for recorded music is something lawyers do enforce, so the documentarian asked Emmett for a new piece that would hit all the beats of the forbidden Bourrée. That became “Swirling,” which you heard above.

Replacing a Bourrée, which is based on a 400-year-old French dance rhythm, got Emmett thinking about other old forms — “allemands and gigues and passacaglias” — and soon he had a growing collection of pieces that seemed new and timeless at once. He played another one for me, called “Slinky.”

This was turning into a coherent project. A man and his guitar; everything that led to this moment; and how it sounds now. He asked his editor at ECW Press, who had already published a book of poetry and a charming memoir from him, whether the album-and-book-length-liner-notes project could be a thing. Now it is.

Like late-period art from a lot of serious creators, the music on Ten Telecaster Tales is beyond genre. It’s its own thing. It’s charming, intricate, quiet but — taken across the arc of 10 very different pieces — quite ambitious. If I could reduce the immense cultural appeal of the guitar down to a single claim, it’s this: in the right hands, a guitar can do anything. And Rik Emmett’s hands are still good.

Gear Acquisition Syndrome: an autobiographical pause

Early in our interview, I told Emmett I ignored Triumph in their prime, which was roughly my high-school and university years. I even told him I was more of a Rush fan, which if there were such a thing as fighting words in Canadian rock, surely those would be it. It’s hard to imagine a more obvious argument against interest: the interview was unlikely to go better if I told my interviewee I sat out the prime of his life. But as I suspected, it didn’t go worse, because a guy who spent a decade filling stadiums didn’t need my ass occupying a seat in any of them.

But by the end of 2024, the instrument at hand — guitars in general, and specifically the Fender Musical Instruments Corporation Telecaster — had worked its way so far into my head that I began to make rash decisions.

I didn’t touch a guitar with musical intent until well into middle age. I was a minimally acceptable student of classical piano in middle school, then a better trumpeter in high school. I even considered a career in music. I’d have been some kind of jazz trumpet player, I suppose. It’s very much for the best that I found things I could do better.

But an electric guitar plugged into an amp? No thanks. Guitars, with six strings tuned in two groups, confused me. And as a weapons-grade band nerd I didn’t understand how a guitar could be a serious instrument if some of my friends who had no musical credentials could play the things by ear and rote.

By late 2024, however, I found myself thinking about guitars a lot. Part of it was a burgeoning fascination with the music of Julian Lage, a former California child prodigy whose jazz is based on a deep familiarity with the instrument’s Americana roots. (Rik Emmett name-checks Lage early in Ten Telecaster Tales.) Part of it was my growing interest in a bunch of singer-songwriters, especially Donovan Woods, who seemed lucky to me because he can carry his band around with him in his guitar case anywhere he goes.

Then, three weeks after Donald Trump won re-election and before we all put our elbows up, my wife and I visited Nashville.

We saw Vince Gill and Amy Grant at the Ryman Auditorium, and if I don’t know much about guitars I know even less about country music, but Vince Gill was so obviously a masterful guitarist that even I got it. And we attended a Monday lunchtime songwriters’ round at the Listening Room, one of a bunch of clubs dedicated to these informal showcases for up-and-coming songwriters.

It seemed everyone in Nashville had a guitar. What was my excuse? A week after we got home from Nashville I bought a Telecaster.

Progress has been slow. It’s true what they say about old dogs. At first I couldn’t hit the correct string even half the time. Why do they put them so close together? And, as every rookie guitarist knows, the first few hundred chords hurt your fingers.

But I know vastly more now than I knew then. Sometimes, for a few bars at a time, I can even play things that sound like music. The best thing is that I hear any music with a guitar in it differently now, because I’ve glimpsed — barely glimpsed, but still — all the thought and care that goes into it. So when I saw that Rik Emmett has been thinking about Telecasters too, I scheduled a talk.

The Triumph chapter

Emmett’s 2023 memoir, Lay It On The Line, has nearly two dozen chapters. One carries a pointed title: “The Triumph Chapter.” As in, the only chapter about Triumph you’re going to get. He did a bunch of things before Triumph and a bunch after, although when I pressed him for stories about the after-Triumph part, he corrected me gently: “You never really leave Triumph.”

Things were frosty with the other guys for a while after Emmett left in 1988. They’re fine now. They do events, they visit sometimes. This weekend a tribute album will be released, with artists including Lawrence Gowan, Dee Snider and Nancy Wilson singing Triumph tunes. The guys are doing some promo work around that, although, since I don’t live in that world, my interview request had nothing to do with it.

Triumph was a business proposition. The older guys, drummer Gil Moore and bassist Mike Levine, hired Emmett. “It was a professional relationship between three partners right from the get go,” Emmett said. “It wasn't like we were kids together, dreaming dreams…. This [was] going to be our attempt to crack the big time.”

They preferred to play smaller venues as headliners rather than bigger ones as an opening act. At least the fans would remember they’d been at a Triumph show. The band liked playing in the U.S., because the same two hours of work would get premium pay, thanks to exchange rates on the greenback. They cheerfully accepted and acknowledged corporate sponsors. Gil Moore had an elaborate crowd-control barrier built for the band’s concerts — not just to keep the fans off the band, but to keep the fans safe from the band’s elaborate pyrotechnics. Then Triumph found they could lease the barrier out to other touring acts when they weren’t on the road. A nice bit of countercyclical revenue, free money while the bandmates were home with their families.

All this money allowed Emmett to build his parents a home, belatedly assuaging their concern about his career path. And as calculated as the business decisions were, he still feels good about the music.

“There's nothing that I do in my life where I don't go, ‘How can I make this be something where I'm proud of it,’ you know? Where there's some some integrity to what I'm doing.” It’s what he taught his students at Humber: “Values and qualities have to be in everything.”

He even believes he helped focus the band’s sense of itself.

“They called the band Triumph. But there wasn't anything really triumph about it, the way that they envisioned it — until we had songs like ‘Lay It on the Line’ and ‘Hold On to Your Dreams’ and ‘Fight The Good Fight’ and ‘Never Surrender.’ Now there was this integrity to what the band was trying to be, and it helped set us apart from the other bands that were like, studs and leather and Harleys on stage.”

Quitting the band wasn’t a rebellion against commercialism. At first he’d have been fine with more commercialism. But he was pushing 40 and grunge was happening, and the market couldn’t sustain him at stadium scale. So he’s spent 35 years playing what appealed to him, which changes over time. It no longer requires pyrotechnics. Enough old fans, joined by new fans, are always happy to hear it.

Near the end of our interview I asked Emmett when he first knew music was his calling. His answer surprised me.

It happened when Emmett was playing football for Bloor Collegiate, showing real athletic promise. “I got blindside blocked by a guy from Danforth Tech. He tore up my right knee. And, you know, no more ACL, badly stretched MCL, cartilage damage.” His sports career ended right there.

He already had a terrible acoustic guitar, of the sort that fall randomly into kids’ lives all the time. Pretty soon he was at Long & McQuade on Yonge Street, putting down $250 for a proper Telecaster. Plus as much for an amp. Plus a union card from Local 149 of the American Federation of Musicians, so he could sit in with his friend’s uncle’s polka band.

All of this was serious money for a teenager in the early 1970s. For young Rik Emmett with his bum knee, it was a capital investment against future earnings. He had no interest in suit-and-tie jobs, and if he couldn’t play with the Argonauts, he’d just find a different path into stadiums.

It didn’t work out too badly at all.

Rik Emmett’s book Ten Telecaster Tales (ECW Press) is for sale in good bookstores. His album Ten Telecaster Tales is available on all the big music streaming services. I won’t be playing anywhere near you anytime soon.

Here’s complete video of my interview with Rik Emmett, from my Youtube channel. Like and subscribe what you find there for more video content.

I had Rik as music business teacher, and songwriting teacher, at Humber College, some years back. Without a doubt, he was one of most passionate and dedicated instructors I've had, either at school or in a professional setting. We would, on multiple occasions, get emails at 11pm giving expanded answers to questions he had partly answered in class.

And he wouldn't take crap work from anyone. The final assignment in music business class was to create a full touring plan for a band. You make up the band (or it can be your band), you find opportunities, figure out where to play, where to stay, daily schedules, routing, and, of course, create a viable budget. He did not appreciate people handing in single-page plans, without any actual research having been done - his reputation as a tough but fair marker was well-earned. In a world where many teachers just want to pass you through the class without hurting your feelings, Rik really wanted everyone to learn and improve by doing.

And of course, as you discovered, Paul, he loves a good anecdote. Thanks so much for this evocative profile.

What great story telling! While I never got to know Rik, Gil and Mike are dear pals and we all spent some amazing times when Triumph ruled the airwaves on the kind of rock radio I was involved with back in tha’ day. Those three guys defined a part of Canadian musical culture and we are stronger for them. Thanks for a wonderful piece,Paul.