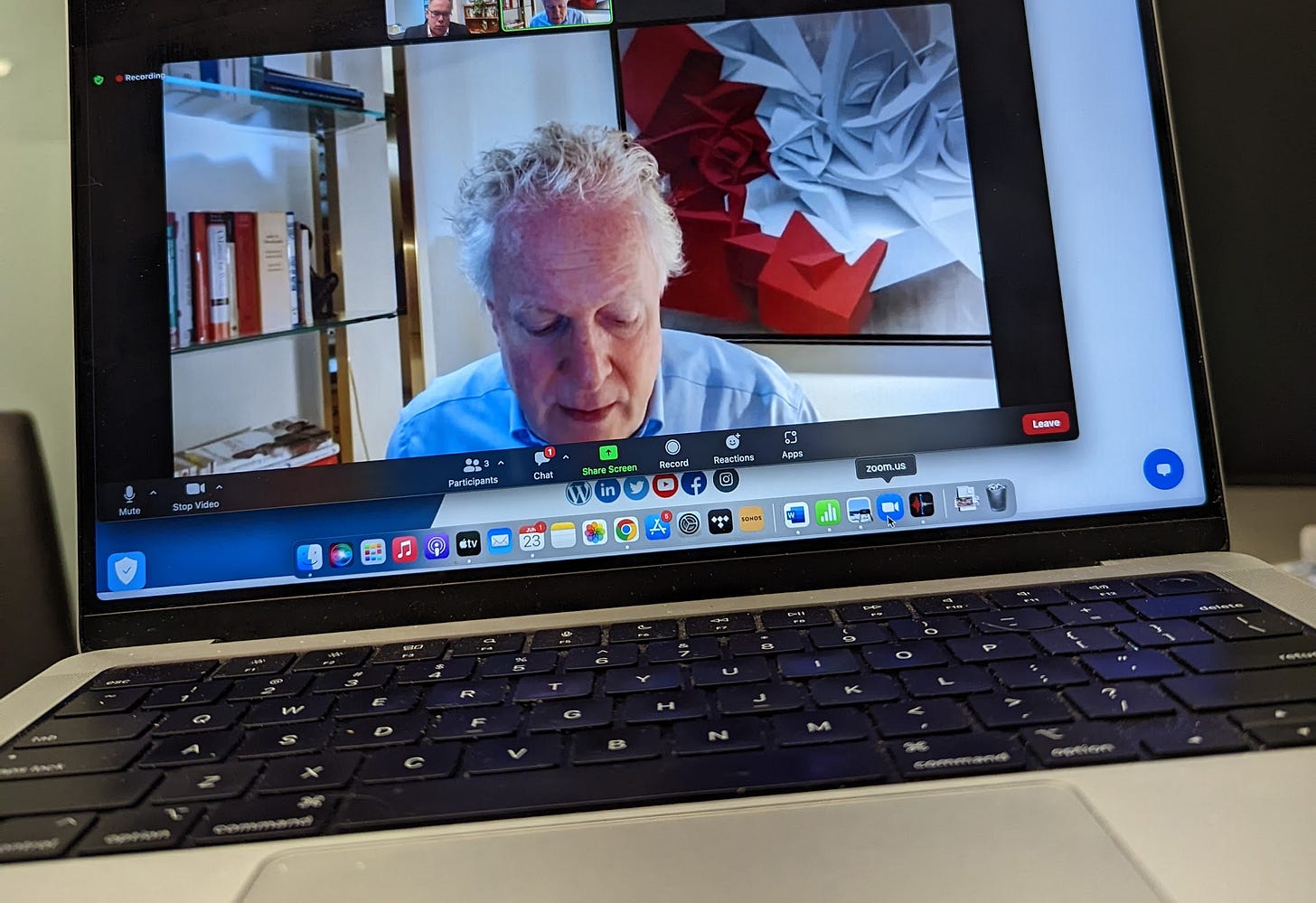

My interview with Jean Charest

In which I didn't ask him about That Guy or That Other Guy

I had 15 minutes on Zoom with the former premier of Quebec and current candidate for the leadership of the federal Conservatives. This is generous for TV, stingy for print, but I decided not to quibble. My list of preferred interview subjects from the Conservative leadership field is short. I still hope to talk to Pierre Poilievre, and have decided that if he keeps congratulating himself for his boldness from a safe distance, I get to judge. Scott Aitchison wants to talk, and I’ll probably do that. I might be persuaded to talk to Roman Baber. That’s the end of my list. Sue me.

I met Jean Charest 26 years ago. I was surprised that he got into this race. I don’t know how well he’ll do. Given time constraints, I decided not to ask him about his main opponents: Pierre Poilievre or the man Charest would face if he won the leadership, Justin Trudeau. This had the effect of making Charest talk about how he would lead the party and a government, not how he plans to get there. My questions in bold, his answers in plain text, everything edited for length and clarity.

Let's skip the campaign. Let's assume that you've won. And then the question is, can you lead this Conservative Party? It includes Candice Bergen, the interim leader, who greeted the truck convoy protesters. Andrew Scheer, former leader and still a prominent Saskatchewan member, who was very close with the convoy protesters.

Can you assert your authority in today's Conservative Party?

I obviously believe I can. And I don't minimize all the divisions within caucus. I'm not minimizing that. And the fact that the day after I win the leadership, people will ask themselves, ‘Is there a place for me with this leader?’

That's what happens after every leadership race. The party, I think, is in need of a leader who's going to be a unifier, has experience leading a caucus, which I have both at the federal and at the provincial level. It'll require a lot of attention and time, but that's what leaders are expected to do. I will be very dedicated to that task.

There's two things: get them to work together on a common plan, vision, what it is that we want to do for the country; and to develop cohesiveness within the group. You know, a good leader creates an environment in which people can maximize their talents and their abilities. You need to mentor them, you need to support them.

To return to this question, which isn't a policy question but I think it's a damned interesting question: The last time you sat in the House of Commons, most of the small-c conservatives in the House of Commons were not in your caucus. They were the Darrell Stinsons and the Myron Thompsons and the Preston Mannings. So, while a lot of people have been accusing you of changing since the late 90s, the fact is that Canadian conservatism has changed since the late 90s. How do you address that in your political action?

I have been very determined in saying, ‘What are my conservative values?’ Repeating them a lot. Because, yes, because it's an issue that people have in their mind, a question. So, what I consistently do try to do is remind folks of what values I believe in. That includes six things that I name. Fiscal conservatism. As you know that was very much the agenda that I pursued [as premier of Quebec].

The second value is the market-based economy. The third is economic policies that promote economic growth, including for resources. And then families, I say, plural. In Quebec, of course, the daycare policies originated under the Péquiste government, but we pushed even further with parental leave, re-establishing family allowances, and weighting all of this in favour of low-income families. Also rule of law which has been an issue in this campaign because of Mr. Poilievre’s support of an illegal blockade. And our way of practicing federalism, which is also a key element here, because the country needs a government that has the ability to function and get the most out of the country and prosper and get big things done.

So those are the six values that I speak to. They’re not exclusive and they may not be the only ones, but for me, it's the core. What like-minded Conservatives believe in.

When you resigned as Liberal leader in Quebec in 2012, did you think you were done with politics?

Yes, I think pretty much so. It was 28 years [since his first election as a Progressive Conservative MP in 1984]. And when I started, I never in my wildest dreams thought I would be involved 28 years.

Is there anyone in particular who made you decide to get in this time?

Alan Rayes. I'll explain the circumstances. The last time around, when the leadership opened up after Mr. Scheer left, there was a lot of friends from over the country who sent emails and messages saying, ‘You should run.' You’d be the right person for the job. Country needs you.’ But after looking at it back then, I wasn't convinced. And then in this case, when it opened up, Alain was one of the first. He was the first person to call me. I was in London at the time, on business. He made a plea that I run and that's what, for me, made it a choice, which would not have been the case otherwise. Now, why him in particular? Remember, he's from Quebec. He's an MP from Quebec. One thing I understood all along about me running is that I would have to have substantial support here in Quebec, from my base. It’s not possible for you to run from somewhere if you don't have that support in your home province.

You’ve passed the cutoff for new membership sales. What phase of the campaign are you in now?

It's been, for me, an experience, because we started the campaign still during COVID, and so it's been hybrid. It's unlike any experience I've had in the past — a lot of time on Teams and Zoom and calls and telephone town hall meetings, and travel.

The other part that has been unusual for me, that [his campaign staff] demanded that I adapt to, is a campaign where there's no headquarters Everything is éclaté [broken up]. The structure of the campaign is very different from anything else I had experienced. And I came from a very structured world in politics.

And the third thing is that there hasn't been that direct contact with the campaign team. That — being in their presence and each other's presence — that I thrive on. So that's been, for me, a period of adaptation.

The recruitment phase we've just been through, we all had a sigh of relief when it was over because it's like running a marathon. Now it's a persuasion mode.

So we're waiting for the interim list [of party members, which the party will distribute to all candidates] so that we have the tool that we need to be able to talk to the people we need to talk to, do the research we need to do, ID our vote and find out where their mind is, figure out what is it that they have on their mind and where’s our potential to gain support.

So we're moving into the persuasion phase and we'll be talking about some things. One of them is, What is it that we care about the most? My view is, number one is going to be the economy. I want to present a very strong economic plan to the country. And we are going to be the party of the economy. The second thing is, from a partisan point of view, we need a leader able to win, and expand our base, with made-in-Canada conservative policy.

The last thing I want to ask about is this eruption of Quebec politics into national politics. Bill 21. Bill 96. As a premier of Quebec, you would have been adamant that the federal government should have no say in questions like this. As a candidate for federal office, you have to say the opposite.

Well, actually on 21, this issue came to me as Premier. In another form, but very much the same issue. After I put together the Bouchard-Taylor Commission, after the 2007 election campaign, it became a very hot debate in Quebec and one that was difficult to to engage in because it was so emotional. So what I did at the time, Paul, I created the Bouhard-Taylor Commission to bring some order to this dialogue so that we could understand what it was about.

That was my objective: Bring the temperature down, so that we could have a reasonable conversation about what this was really about and how it was going to impact Quebec society, which is particular and different from the rest of the country. The future of language, culture, the insecurity about our future.

So, Bouchard and Taylor tabled their report. And in the report, they recommended that we outlaw religious symbols for government workers in positions of authority, which would have included police officers, jail guards, judges. And I refused to do it, for two reasons. One was purely legal: because the advice we were getting from the Department of Justice was that this was contrary to the Quebec charter and contrary to the Canadian charter.

And the second reason was, I felt it was wrong. There was no empirical evidence that would justify the restraining of individual rights. And if you do that, you need evidence to do it. You don't just do it because there's some sentiment. These are rights. And that's why we have Charters. And I wasn't about to invoke the Notwithstanding clause to do this.

So when this issue was raised in the current leadership campaign, my position is to say, well, it is provincial jurisdiction. I get that. Is it popular? Yes. We, the federal government, are we going to go out there and initiate court action? No. But if this goes to the Supreme Court of Canada, my government will speak to it. We are not observers in our own country.

Now, interestingly enough Pierre Poilievre came to Quebec and said, ‘No, I'm not going to go to the Supreme Court.’ He wasn't saying the same thing in English Canada. Which is why I pointed out to him, in the French debate that, you know, being bilingual is saying the same thing in both languages. But then he he got out of it by saying, ‘Well, I support the federal government's new position,’ that they had expressed on the same thing.

So, that's where I am on these these matters. There is a strong preoccupation with the fact that we have a government [in Quebec] who, at the outset of legislation, does two things. One, invoke the Notwithstanding clause. And two, blanket its legislation [i.e., make the Notwithstanding clause’s opt-out from Charter rights apply to the entire law rather than specific sections], which has never been done before.

Now, there are other options, you know. You could always do a referral to the court of appeals in the province. Remember, we did that in the case of the federal government wanting to create a national securities regulator. You may remember, we did a court of appeals referral at the time, which gives some order to the discussion and allows legislators to have bearings.

There are options to dealing with this, but the government [of François Legault in Quebec] chose another course. And thus, this issue that we have now.

So that's where I am on this.

It’s interesting that he didn’t really answer the first two questions about how he could effectively lead a party whose overall vibe is radically different from his own, not just in terms of conservatism but more broadly in terms of democratic norms and the rule of law. I guess the most accurate answer would be, “About as well as O’Toole did, if I’m lucky,” which is probably why he left it alone.

It was also interesting that the most fulsome and engaged response he gave was to the question about Bills 21 and 96, which might suggest that at the of the day, Québec issues are the ones still closest to his heart. Which is fair, of course, but might further remove him from the warm affections of the western Conservative base.

I think his chances of winning the race are remote, and if he did, his chances of steering that party towards government even more so. But I’m glad he’s making the effort, one that he clearly doesn’t need to and seems to be doing primarily to put up a good last fight for Progressive Conservatism, among other things.

I’m not a Conservative but after 50+ years I would consider voting for this voice of reason.