In 2026, build

For too long, Canada has thought of itself as the world's warehouse. Time to change that

That’s quite an interview Tim Hodgson gave to La Presse in the last days before Christmas. “This document is an alarm signal,” Hodgson told Joël-Denis Bellavance, referring to the Trump administration’s national security strategy.

Hodgson carried a heavily marked-up copy of the US document into his meeting with La Presse and “took the time to read some extracts from the document out loud” during the interview, Bellavance notes. These included references to a “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,” the intention to “deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to … own or control strategically vital assets in our Hemisphere” and the use of America’s military in “establishing or expanding access in strategically important locations.”

“We know what the Monroe Doctrine means,” Hodgson said. “That’s like America’s Manifest Destiny. What’s Manifest Destiny? It’s the believe that the united States are destined to rule the Americas. That’s the world we live in today.”

“We live in a world where we are regularly told we should be the 51st state. It is a world where Denmark is being asked to relinquish its territorial sovereignty. We live in a world where authoritarian leaders believe they can change Ukraine’s borders by force. We live in a world where China has made it clear that it intends to annex Taiwan by force, if necessary. We live in an extremely difficult world. We must deal with it. The trade war has been imposed on us, and we must respond.”

I still haven’t really figured Hodgson out. But it’s probably significant, since he’s Mark Carney’s star cabinet recruit, that he spends time using a highlighter on the bits of the neighbours’ policy bible that mention “strategically vital assets” and “strategically important locations.” Keeping an eye on the neighbours is probably a good idea. In the same week that La Presse published the Hodgson interview, President Donald J. Trump appointed Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry to, as Landry wrote on X, “make Greenland a part of the US.” Later the same day, Trump unveiled plans for a new “Trump class” of battleships and warned the Venezuelan regime of Nicolás Maduro not to “play tough” as US naval vessels commandeer Venezuelan tanker after tanker. (Canada also rejects Maduro’s claim to govern Venezuela legitimately, although more mildly.)

I doubt Trump’s administration has short-term plans to treat Canada the way it’s been treating Greenland and Venezuela. But it doesn’t feel like the safest bet I could possibly make. And in the meantime, these simply don’t seem like reliable neighbours. Much of our politics in 2025 was about how to respond. That will surely continue through 2026.

In some ways it’s obvious how to respond to a changing United States. (i) Keep as much of the bilateral relationship as can be salvaged, consistent with Canadian values and the whims of the White House incumbent; (ii) seek other markets and friends east, west and further south; and (iii) build up a Canadian community that’s less dependent, not just on the Americans, but on anyone. Option (i) will be frustrating, and just about everyone will disagree on terms. Option (ii) will take years.

Option (iii) probably gets the least attention. It should get more.

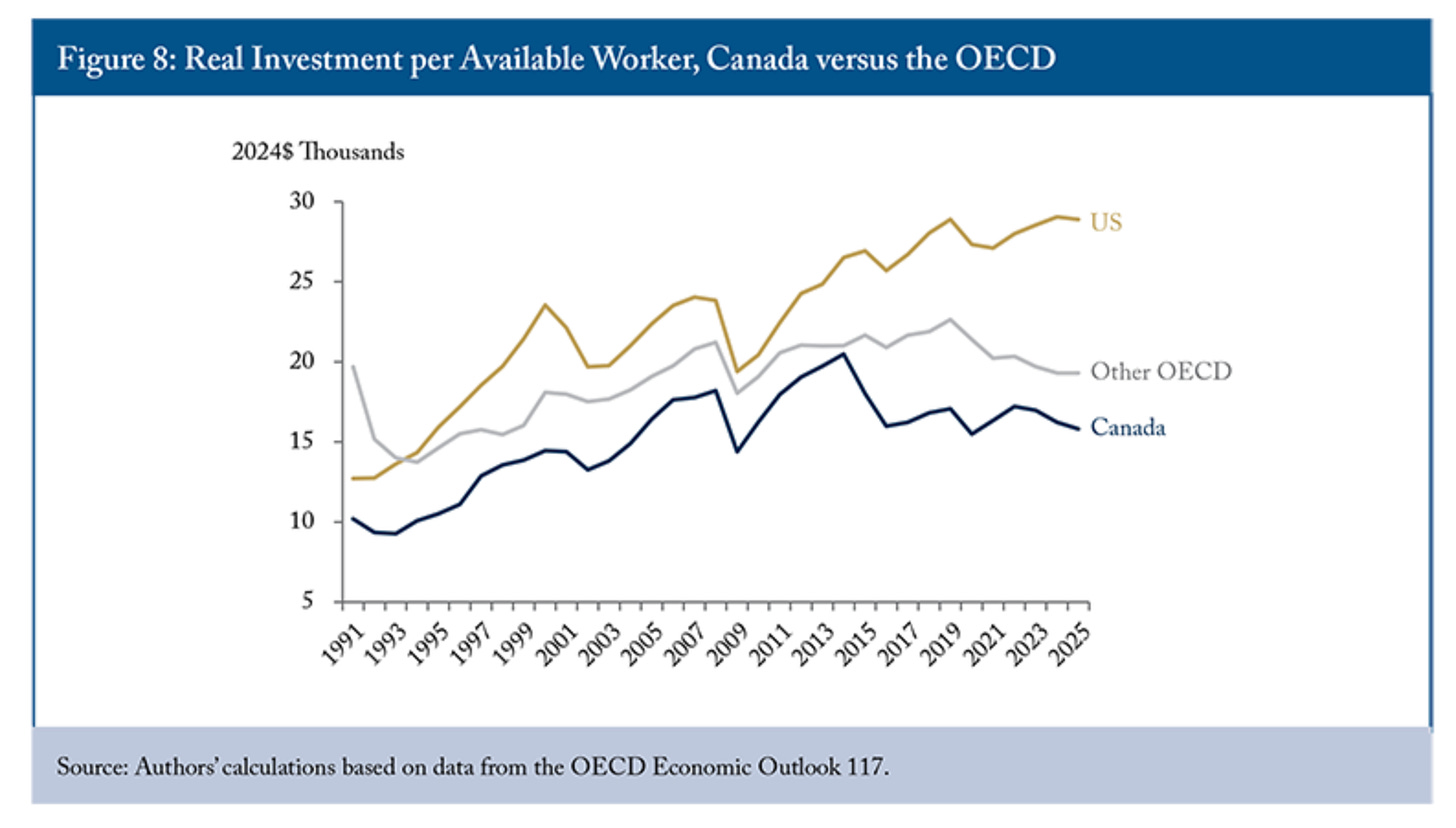

Canadians aren’t builders. We have been, sometimes. We still are, sometimes. But lagging investment in Canada, especially business investment, is almost a cliché. In 2024 Carolyn Rogers, senior deputy Bank of Canada governor, called lagging productivity “an emergency.”

Here’s a chart from the CD Howe institute.

Here’s the study it’s from. Or maybe it’s from this eerily identical study a year earlier. It’s hard to tell. In both studies the authors trot out a bunch of possible explanations — over-regulation, less exposure to both risk and opportunity, and a bunch of other familiar worries.

May I suggest part of it is simply that building stuff is so rarely mentioned as an option in Canada? In any context. Drive through any small town a few kilometres from the border; the quality of road paving, sidewalks, recreational facilities and a bunch of other clues will tell you pretty quickly which side of the border you’re on. The biggest convention centre in Germany is seven times the size of the biggest one in Canada. Almost the only point of temporary foreign-worker programs is to make menial labour competitive with capital investment, or rather, far cheaper. Here’s an article that says so. Here’s a book, deeply sympathetic to the workers.

I sometimes try to be more methodical with my analyses, but today I’m just trying to convey an impression. A vibe. When the Liberal government spends one-quarter of one percent of expected outlays on its marquee investment-encouragement scheme, I think introspection might be in order. Part of it, as I’ve written, is that the prospect of government partnering with business is fascinating to government but terrifying to business. But surely part of it is also that building things simply rarely occurs to Canadians — to Canadian businesses, communities, even individuals and families.

Here’s an update on a story I have mentioned every several months for years. There’s a connection to today’s topic.

In December 2020, five years into the Trudeau government, Infrastructure Minister Catherine McKenna announced the first-ever “national infrastructure assessment,” to determine where and what Canada needed to build. She launched consultations on the project in 2021, and received results from the consultation a few months later.

And then nothing happened for years. At the end of that summer, McKenna announced she wouldn’t run for Parliament again. She was replaced at Infrastructure by Dominic LeBlanc, and then, in the manner of late Trudeau-ism, by assorted random passersby. It was Sean Fraser who finally appointed a “council” to actually do the assessing — three years after the results from the consultation came in. Here’s the council. Impressive CVs. By coincidence their appointment came 10 days before Chrystia Freeland resigned as Trudeau’s finance minister.

Chaos ensued, and a new Liberal leader and an election. I’ve heard no mention of the new Assessment or the Council in public statements from the Carney government. But that doesn’t mean the process came to a halt. Sometime in March the mandate of the Assessment was narrowed to a focus on “the public infrastructure needed to build more houses.” In September the Council started releasing consultation reports and technical papers every two weeks, and at the end of November it delivered a jackpot: Canada’s first National Infrastructure Assessment, five years after one was promised and a decade after a Liberal government started spending money hand over fist on infrastructure.

I’m unable to find any general-interest news organization that covered the report’s release. A construction industry newsletter was pleased.

I’ll get to what the Assessment said, but the first thing to be said is, this is how things go when a lot of people don’t care how things go. It’s not serious for a government to start planning half a decade after it starts spending. It’s not serious to forget, for more than three years, that it was supposed to be planning. And when the government releases its plan and nobody notices, it becomes clear that seriousness isn’t lacking only in government.

The Infrastructure Council suggested, in its first “What We Heard” report in September summarizing the consultations it held, that this is pretty much business as usual. This paragraph is long, but it’s worth reading every part, and remembering that it’s the first thing this group of experts said to the government that was perilously late appointing it, once it was finally in a position to say anything at all.

“We consistently heard that infrastructure planning and delivery in Canada has become incredibly, unnecessarily, complex, and is failing to respond to the needs of Canadians. We are not building the infrastructure we need, where we need it, and at a pace that responds to this moment and prepares us for the future. The landscape involves multiple orders of government, sometimes working at cross-purposes, contributing to a complex regulatory environment and unfeasible approval timelines, overly restrictive and uncoordinated planning, fees, and funding, that together fail to incentivize good development. At the same time, significant gaps in data availability and access make it difficult to plan effectively and to prioritize investments. As an example, Canada ranks among the lowest Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries in terms of the time required to obtain a general construction permit…”

The Nov. 28 Assessment itself offers similar stuff. “More than $126 billion of housing-enabling infrastructure is in poor or very poor condition and at risk of failure in the near-term,” it says.

And, “We face a shortfall of millions of homes, with affordability slipping out of reach for many Canadians, particularly young people, newcomers and marginalized communities.”

And, “The Parliamentary Budget Office estimates that 290,000 housing units need to be built annually to close the housing gap, 65,000 more per year than are expected.”

And, “Water losses in Canada have increased from 13% in 2011 (673 million litres) to 17% in 2021 (806 million L) of total drinking water use, roughly equivalent to the total drinking water consumed in British Columbia in the same year.”

And, “Historically, Canada has had significantly worse leakage rates than peer countries, largely due to insufficient water loss control practices (e.g., leak detection and repair).”

And, “In 2022, only 27% of waste was diverted from landfills or incineration, placing us 17th out of 38 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and well behind leaders like South Korea (54%) and Germany (45%). Even countries with relatively similar economies and geography, like New Zealand (35%) and the US (30%), are doing better.”

I could go on. They sure do. Remember this sort of thing when the dwindling Trudeau wing of the Liberal Party spends much of 2026 claiming that Mark Carney is ruining their beautiful legacy. And keep it in mind if, sooner or later, the Liberals finally lose an election to a Conservative Party whose leader has insisted all along that making things is incredibly, unnecessarily complex.

But results like this come from something broader than one faction or party. There’s a profligacy here that’s cultural, the product of a society that spends most of its time debating income support versus tax cuts, and mistrusts investment in physical and human capital. For too long, we’ve treated Canada as the warehouse for the rest of the world, a cheap, cheerful and slightly chaotic storage depot for the stuff more sophisticated countries need.

I’m half a decade into picking on Trudeau for something he wrote in the Financial Post when he was a candidate for the Liberal leadership in 2013: “What if our goal was to become Asia’s designer and builder of livable cities?” There was a level of presumption in that question that remains a little breathtaking. It’s fair to say there aren’t a lot of people in Asia hoping some Canadians will come along to design and build their cities. Maybe it’s time, at last, for Canadians to become Canada’s designer and builder of livable cities.

There are places that are trying to think big. In Goderich, ON, there’s a project to quadruple the size of the town’s port for a vast expansion of lake-borne transport. Calgary’s putting half a billion dollars into a downtown cultural campus, having already doubled the size of its convention centre. Regional rail around Montreal continues to have growing pains, but I took a ride the other day and what’s in place so far is impressive.

What’s been missing is a mindset, a general shared belief in ambition and quality in both public and private investment. Investments in physical and human capital aren’t automatically wise, so honest political debate will accompany every decision, as it should. But it’s harder to maintain the mindless, rote polarization that’s come to characterize our online lives when people are trying to get things done in the real, three-dimensional world. Building things is so hard, there’s less time for tribes.

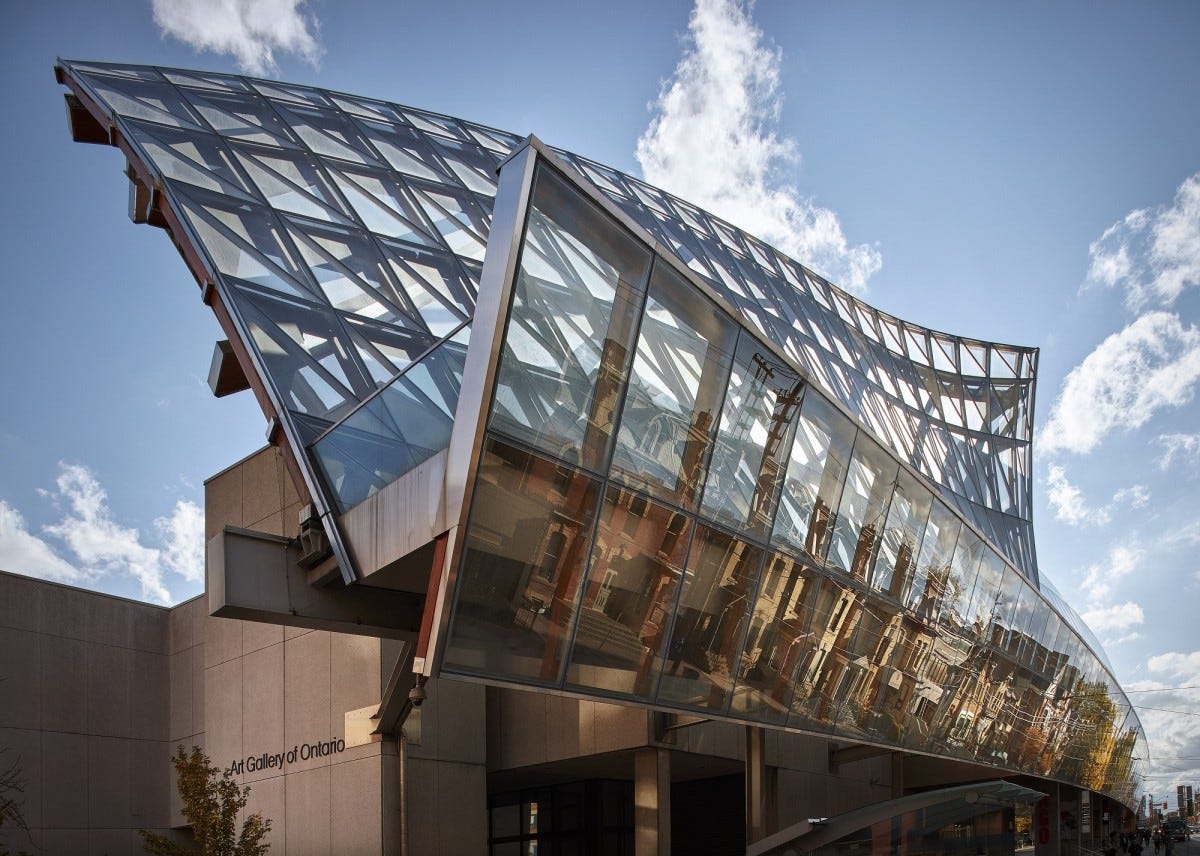

In December, the world lost Frank Gehry, the Toronto-born architect who transformed countless cities. He left Canada early and did only occasional work here, including his remarkable expansion and transformation of the Art Gallery of Ontario. He became a designer and builder of livable cities in other places. We don’t really go in for that sort of thing here. But we could.

This is a sobering article to read but it certainly exemplifies the sepsis that has settled into our nation's will to work together and achieve great things.

I find it very troubling to see how much effort is expended to prop up mediocrity. Examples of this are everywhere, starting in classrooms where teachers unions fight tooth and nail (and abetted in their efforts by progressive activists) to avoid testing students to determine national outcomes of learning. How the hell are we supposed to determine if our very expensive public education system is delivering results for children if we don't investigate learning outcomes and compare it with data accrued over time? Our children are our future leaders and should be seen as an infrastructure investment that will underpin a buoyant economy going forward.

Another example of mediocre expectations is the Liberals flaunting of their spending prowess and austerity because Canada ranks _____ (you can fill in the blank) in the G7, G20 or ____ for debt against GDP. Oh great. Measuring our own fiscal mess against WORSE basket cases is a fantasy world of ineptitude. Canada should strive to be the BEST country with the cleanest balance sheet that is developed by prudent, targeted spending and a vibrant economy that everyone participates in.

Finally, all levels of government spend too much time directing human capital and spending in areas outside of their jurisdictions. Ottawa has no business being in a national school lunch program, and municipalities have no business being involved in "affordable housing" when sewage and clean water upgrades languish and the tax base withers on the vine.

2025 has been described as the year that Canadians rediscovered nationalism. Perhaps, but there is still a long way to go as long as we are still prepared to tolerate mediocre leadership and outcomes.

We only have to look at our own city, Ottawa, to see the incompetence and worse that holds us behind. The question is why do set the bar so low for our politicians and for their bureaucracies who are frightened of collecting data to know what is working and what isn't?