In hindsight, we should have known the serious talks began as soon as everyone started saying they were over.

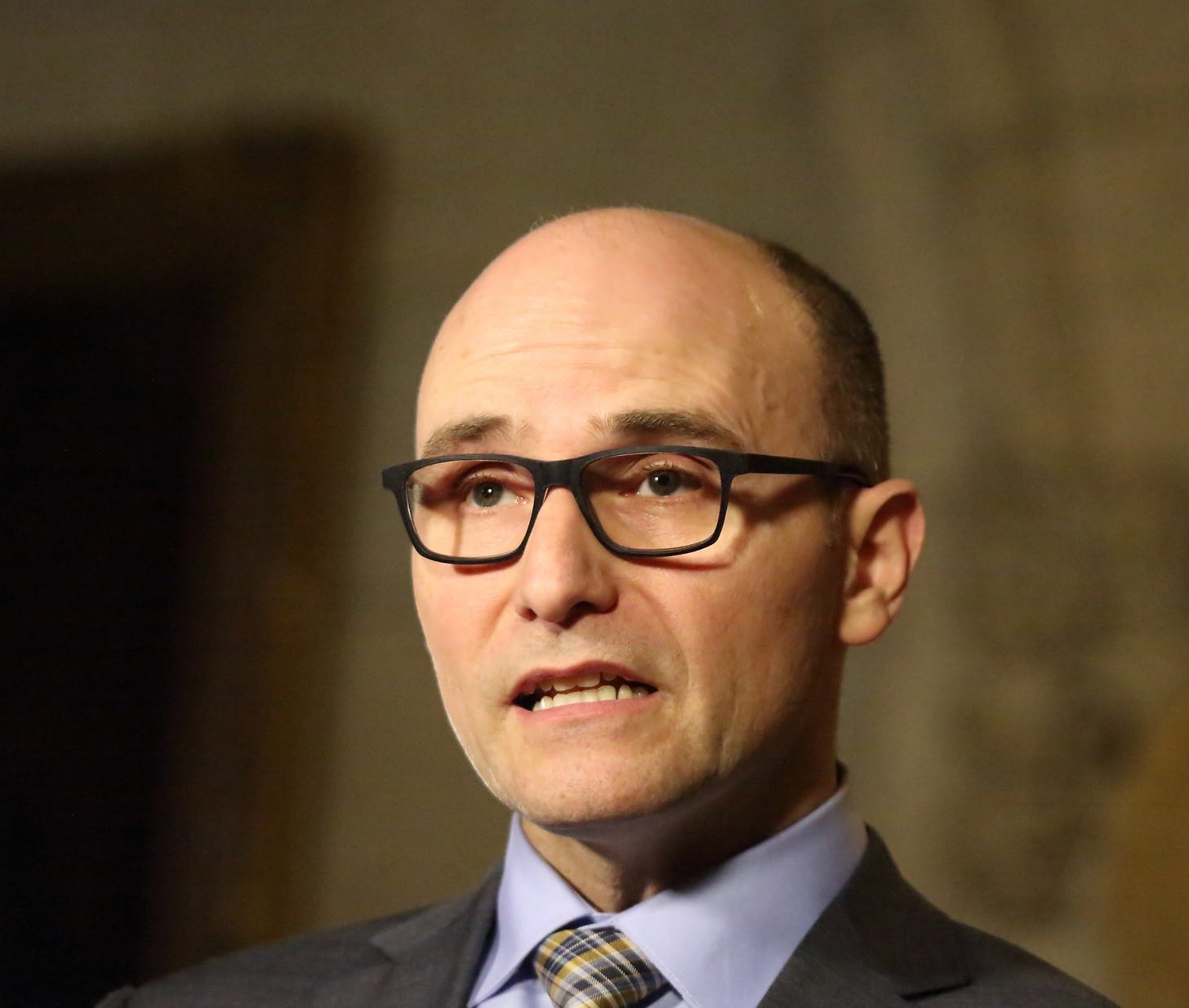

On Nov. 8, federal health minister Jean-Yves Duclos met his provincial counterparts in Vancouver for the first in-person meeting of federal and provincial health ministers since 2018. The meeting collapsed in acrimony. Provincial premiers blamed Duclos for refusing to talk about money. Duclos, in a cringey statement I am sure was written by a seven-staffer army of junior comms people, blamed the premiers for insisting on talking about money.

“The Premiers are preventing us from taking concrete and tangible steps that would make an immediate difference in the daily life of health workers and patients,” Duclos said. “Premiers keep insisting on money and a First Ministers’ Meeting. Once again, I will be very clear: before we start talking about the means, we need to talk about the ends. And that can only happen and continue to happen at the Health Ministers’ Table.”

Clear enough. No discussion of money before agreement on reform. And that “can only happen” among health ministers.

Of course this statement was meaningless. On Dec. 9, provincial premiers called for a first-ministers meeting on health in early January. Reacting in Ottawa, Duclos said “Well, the Prime Minister meets with Premiers almost every week.” But not all at once, a reporter interjected. “Well, the Prime Minister will obviously do what he wants to do,” Duclos admitted. “I also work and talk regularly with my colleague health ministers. I did so 12 times over the last year, including the last time in person in Vancouver.” This was an elegant way of admitting that the “Health Ministers’ Table” which Duclos called the “only” venue for progress had not operated for a month.

But Vancouver suddenly looked better in hindsight. “In private, we all agree on the diagnostics that our health-care system is showing, the importance of supporting workers and patients, reduce backlogs in surgeries and diagnostics,” Duclos said of colleagues he’d walked out on, a month earlier.

It was a long scrum. At times, Duclos seemed to be arguing pretty forcefully against Ottawa-knows-best solutions delivered from on high:

“In one province, it may be that access to family health teams is better but access to mental health or home care or long-term care is not as good. So yes, on average, it's the same problems and the same solutions should be applied, but the conditions may vary and the speed with which each province may wish to proceed toward solving these specific problems may also vary across the provinces and territories.

“It's not for the federal government to try — and certainly not to pretend to be able — to manage the health care system. Respect for provincial jurisdiction is the most important principle in my relationship with Health Ministers. And that comes, as you said, with respect for the diversity of conditions, the diversity of specific measures and the diversity of speed with which provinces may want to proceed.”

Reporters started to point out that the premiers were pretty eager to go over Duclos’s head to the prime minister, or to whoever is making decisions in his office these days. This unwelcome news rest Duclos to his earlier lines. “A plan to send unconditional transfers to Finance Ministers is not a health plan,” he said. “So that's not a plan that meets the needs of my colleague Health Ministers. The ones I work for are Health Ministers. I'm not there to support unconditional transfers to Finance Ministers across Canada. I'm there to help the very difficult jobs of my colleague Health Ministers and that's also the responsibility that the Prime Minister needs me to do.”

Meanwhile, you will perhaps not be surprised to learn that at about this time, the locus of federal-provincial negotiation moved away from Duclos and kicked into high gear. John Brodhead, the PM’s director of policy, has been talking to officials in British Columbia. Ben Chin, a senior PMO advisor, has been talking to Ontario. That much I know for sure, though one presumes each talks to several provinces and that other staffers, who are not generally submitted to the indignity of scrums, are working the phones too.

I’m told Doug Ford’s Ontario government in particular is eager to accept any federal condition on any transfer, knowing that health is a pressing issue of public concern; that federal conditions will be easy enough to meet; and that, in any case, any conditions would be enforced for all of about 17 minutes by the most easily-distracted federal government since Confederation.

And, even more helpfully, Quebec’s government has been proclaiming since November that it does not view a demand for publicly-available health data as a federal “condition” of the sort that Quebec sometimes feels compelled to reject.

The result of all the back-channel discussion is the flurry of headlines in recent days suggesting a health-care deal is imminent.

It fell to Duclos to discern a change in the provinces’ attitude. “We have seen a shift towards a focus on what matters to Canadians, which are results,” he told reporters in Ottawa on Friday. “Results for patients and health care workers. That's what people want and that's what I believe Premiers also want now. And that's great news for everyone across our country.”

But — but what about the health ministers? The ones he works for? “And great news, I believe, I would also add, for the Health Ministers.” Phew.

I do not like to criticize Duclos. He has given more clear and thoughtful answers on other files than most of his colleagues. I take him to be more thoughtful than most in this government. It’s just that the health-care file, and especially the financing of health care, is bigger than one minister. It is also, perhaps inevitably, bigger than reason. The “shift” Duclos perceives is mostly federal, driven more by calculations of electoral timing and fiscal capacity than by any finely-calibrated sense of Ottawa’s ability to prod or cajole provincial health-care design.

Already a year ago, during his odd one-hour rebellion from assorted Liberal orthodoxies, Quebec City MP Joël Lightbound was calling on Trudeau to increase health transfers to the provinces, rather than waiting until after COVID was “over” to even consider the thing. The federal change of heart didn’t happen quickly. Provincial officials tell me that when they asked about transfers they got the runaround. In early 2022 they were told they had to wait until after an Ontario election. In mid-2022 they were told they had to wait until after a Quebec election.

John Horgan, who for most of 2022 was British Columbia’s premier and held the rotating chairmanship of the provincial premiers, was told he could discuss these matters with a panel of federal ministers comprising Duclos, finance minister Chrystia Freeland, and intergovernmental-affairs minister Dominic LeBlanc. But those meetings either wound up getting cancelled — or they would be held without Freeland’s participation.

I’m also told, by a source close to the Trudeau government, that Freeland has been among the most reluctant to see any momentum toward a health deal. Her April 2022 budget and November economic update revealed considerable late-breaking alarm over Canada’s fiscal situation — and a dawning realization that she’s the one who’s supposed to be worried about such things. She needed considerable coaxing over the necessity for new permanent spending. Which is only natural, given that Justin Trudeau’s first mandate letter to her as finance minister told her to “avoid creating new permanent spending.”

The finance minister’s qualms having been settled or circumvented (there’s a new book about how that sometimes happens), progress toward a health accord has taken on such formidable momentum that what might have seemed significant stumbling blocks are now simply ignored. Witness Ontario’s substantially increased use of private clinics, which would bill the public system.

In an interview with the Toronto Star’s Susan Delacourt, the prime minister gave that sort of thing a big green light. “I’m not going to comment on what Doug’s trying to do on this one… We’re supposed to say a certain amount of innovation should be good as long as they’re abiding by the Canada Health Act.” It’s a classic Trudeau line. When the prime minister of the country says what’s he’s “supposed” to say, I always wonder who’s doing the supposing.

Funny the PM should use the word “innovation.” That’s the word Erin O’Toole, who I’m told was once the Conservative leader, used in regard to private-sector health clinics that would bill the public system, just before Justin Trudeau and Chrystia Freeland dropped a house on him during the 2021 election. If I thought words had any meaning, this sort of thing would cause pangs of regret.

Duclos has been insisting the provinces must deliver better health-care information. I have the same two questions I always had.

(1) Have you ever tried to get information from the government of Canada? Here’s a page of “First Nations and Inuit Health and Wellness Indicators,” definitely in federal jurisdiction, in which the “latest data” — on subjects as fundamental as infant mortality — sometimes dates as far back as the Paul Martin government.

(2) I guess this one isn’t a question. When demanding that something happen, it’s always a good idea to make it something that’s already happening. Over at the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), we see an “indicator library” with information on health indicators from every province, including Quebec, and it’s orders of magnitude more recent than on that sad federal page I linked above.

Probably not one Canadian in 100 knows CIHI has existed since 1994. If re-announcing it, a year before its 30th anniversary, is what’s needed for someone to declare victory, it’s a small price to pay.

As for health-care negotiations that take place entirely between the last failed meeting and the next triumphant meeting, I refer readers to the paragraph I send to everyone who asks about this prime minister. It comes from then-Ethics Commissioner Mary Dawson’s first report on Trudeau, from 2017:

“The meetings he attends as Prime Minister are not business meetings. Rather, they are high-level meetings centred on relationship building and ensuring that all parties are moving forward together. Specific issues or details are worked out before, subsequently or independently of any meeting he attends.”

Apparently he’s not the only one. Subsequently to Duclos’s meeting and before Trudeau’s, the specific issues and details are being worked out.

None of this is a tragedy. I think it’s appropriate to increase health transfers, fair for the federal government to ask for something in return, and also fair for provincial governments, and citizens in general, to notice how limited the federal storehouse of credibility on these matters is. I also think it’s fair for us to notice the gap between claims and reality, and I hope I’ve been useful on that score today.

I had a bit of a falling out with this government in late 2018 after I wrote that what was missing from executive federalism under Trudeau was an executive in the federal chair. This produced exclamations of wounded pride from inside Trudeau’s office. But maybe what I described wasn’t a problem. Maybe it’s just the way things go.

The following is a sample of doctors/1000 population: UK - 5.8, Norway - 4.9, Finland - 4.6, Sweden - 4.3, Australia - 3.8 and Canada - 2.4 (Source WHO). Why is it than so many keep avoiding this real issue. We have a growing population (500,000 immigrant a year for example) and a medical profession that seems to be relatively shrinking. Fix this and problems like no family doctor, wait times and doctor burnout will melt away.

Well I agree with your last remark, Trudeau is not much of a manager, more a master of ceremonies and good at dancing around. Morneau has a point in his book about JT.