Green shifting

Carbon taxes are hard. The Liberals have blown hot and cold for years.

I think the best way I can make sense of Justin Trudeau’s surprising tactical retreat on carbon taxes is to look at his entire history with carbon taxes. On this file, he learned early that his preferred policies could be hard to sell. When you look at Trudeau’s entire history as a Liberal MP, last week’s move starts to look more consistent and, in hindsight, not quite so surprising.

The Liberals have never been sure they could win with a carbon tax. They’ve been right to wonder. In 2008 Stéphane Dion made a clear and elaborate carbon-tax plan, with offsetting tax cuts elsewhere, the centrepiece of his platform. The Liberals ended the campaign with their worst election result since Confederation.

It’s worth remembering that 2008 was Trudeau’s first general election. He managed to defeat an incumbent Bloc Québécois MP in Papineau, something few Liberal candidates managed to do that year. But he spent a lot of time on the road across the country with Dion, and he got to see close-up what worked and what didn’t on that campaign.

In 2011 Michael Ignatieff, formerly a big fan of carbon taxes, ran on a cap-and-trade scheme he rarely mentioned. For reasons having little to do with climate policy, he managed to do worse than Dion.

After 2008 a few old Liberal hands around Ottawa — Chrétien-era veterans — grumbled that Dion should have been content to “lay down a marker:” to say, as briefly as possible, something he could point to later as a promise, and then change the subject fast. “My government will face the climate challenge head on! Mark my words! Now let’s talk about Canada’s great ports and harbours.” Or whatever.

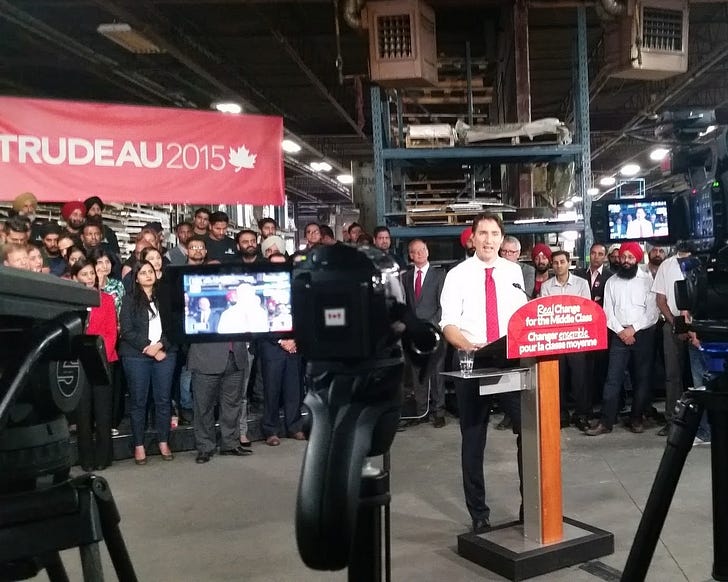

This is pretty much what Justin Trudeau did in 2015.

The term “middle class” appeared 133 times in Trudeau’s 2015 election platform, including in its title. The word “climate” doesn’t make an appearance until Page 13, to set up a promise of “significant new investments in green infrastructure.” If climate policy is a set of things citizens will have to do or endure in return for eventual benefit or reduced risk, the Liberals’ 2015 leaned really heavily on the expected benefit.

The word “carbon” appeared only 10 times. Six of those mentions referred to a “Low Carbon Economy Trust,” a plan to give provinces money to reward them for developing policies that cut carbon emissions, like energy retrofit programs for houses. The other four mentions of carbon were passing references to a price on carbon that would be easily agreed with cooperative provinces. A Trudeau government would “ensure that the provinces and territories have targeted federal funding and the flexibility to design their own policies to meet these commitments, including their own carbon pricing policies,” the platform said.

In the first debate of the 2015 campaign, Stephen Harper mentioned carbon taxes or carbon prices five times. The cheeky moderator mentioned them four times. Green Party leader Elizabeth May mentioned them once, NDP leader Tom Mulcair not at all, and the Liberals’ Trudeau mentioned carbon taxes once. Again he made carbon pricing sound like work that would mostly be done by the provinces and that was, in fact, nearly complete. Thus are markers laid down.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paul Wells to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.