Readers should note that today’s post contains more salty language than usual.

In 1966 a student at the United States Military Academy at West Point named Lucian K. Truscott IV went through his mail and opened the latest edition of the Village Voice. Truscott was 19, strong and tall, crewcut and ramrod-straight, heir to one of America’s great military families. The Voice was a weekly tabloid newspaper, weird by Truscott’s lights, but he was a subscriber because its encyclopedic arts and culture listings made it an invaluable guide for the weekends when he could get to Manhattan on leave.

This week’s edition had a story about Abbie Hoffman, who was against the war in Vietnam and liked to say outrageous things. Truscott wasn’t really equipped to process what he was reading. So he wrote a letter to the editor of the Village Voice: “Abbie Hoffman is an asshole.” Signed, Lucian K. Truscott IV, West Point, New York.

Truscott’s letter ran at the top of the next week’s letters section, which was one of the paper’s most-read features. It drew rebuttals from about half the smartasses in New York. He wrote back to set them straight. Soon the correspondence between Truscott and his tormentors was a staple of each week’s letters section.

Well, one thing leads to another, Truscott winds up at the Electric Circus club listening to Wavy Gravy, and again he can’t believe this madness, so he writes the longest letter he’s written yet. Thousands of words. Since he was still in New York, he walked over to the Voice and slid his tract under the door. The following Wednesday the whole screed ran, starting on Page 1.

Pretty soon Truscott was at the Voice Christmas party in his dress uniform and sneakers. “I opened the door and I hit Mayor Lindsay on the elbow, and he spilled his drink on Bob Dylan,” Truscott told Tricia Romano. I am getting all of this from Romano’s glorious new oral history, The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper that Changed American Culture.

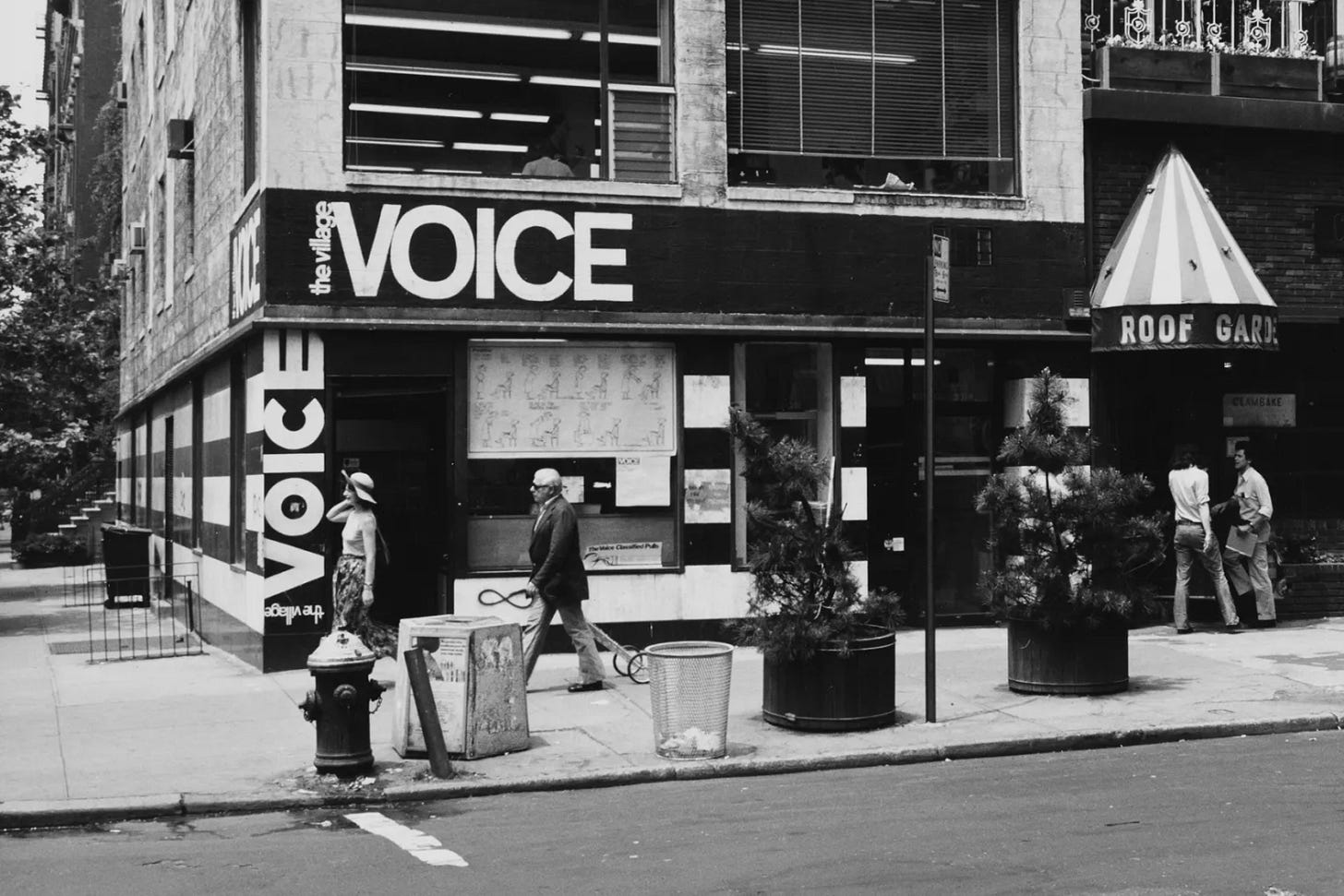

Eventually Truscott became a staff writer at the Voice. Over time he became what he beheld, and as such he also became a subject of the paper’s marketing efforts:

The Voice went on to become one of the world’s most important newspapers, a leading source of street-level news, cultural criticism, hilarity and mourning. It closed in 2018 and has lately kind-of half-reopened, a zombie casualty of the internet like so many others. Romano’s book reminds the paper’s admirers why it mattered, and is therefore a guide to mattering in general. It’s a ferociously entertaining read, admirably complete.

The Voice was founded in 1955 by three WWII military veterans, Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher and Norman Mailer. Mailer was a blowhard (“I have only one prayer,” his first column read, “that I weary of you before you tire of me”) but he knew how to draw a crowd. Wolf and Fancher actually wanted to run a newspaper. The war had shaped them, made them pacifist and suspicious of conformity, which set them up well for American culture’s next few dozen acid baths. Vietnam. The Stonewall riot (the gay bar was four doors down from the Voice’s office; when Truscott’s early coverage of a brutal police raid and the clients’ resistance was dismissive, the fledgling gay-rights movement devoted some of its early energy to picketing the Voice). Women’s liberation. The fight to break Robert Moses’ control over the city’s urban development. Slum lords and the judges who always ruled in their favour against their tenants. And on and on, for half a century. The Voice won three Pulitzer prizes. It built Ed Koch up — he was the paper’s lawyer in the early days — and tore him down, debating along the way whether it should out him. It provided some of the earliest and most combative coverage of Donald Trump, Spike Lee, hip-hop, Off-Broadway, AIDS, ACT UP and Talking Heads.

Talking Heads frontman David Byrne “sings in a high somber voice,” Richard Goldstein wrote in 1976, “somewhat like a seagull talking to its shrink.” If Jonathan Richman, another singer of the era, “plays the kid who ate his snot, David plays the kid who held his farts in.” (“In a good way,” Robert Christgau, Goldstein’s editor, says of his writer’s portrayal of Byrne.)

Greenwich Village was a magnet for people who cared about these things, or were buffeted by them, because it was cheap, residential, at once eccentric and neighbourly. “The original bohemians,” Calvin Trillin wrote in 1982, “were mainly people who came from small, peaceful towns, and they settled in the Village partly because compared to the rest of Manhattan it had the sort of informality and neighbourliness they were used to at home. In other words, it reminded them of the Midwest.”

Romano, who wrote for the Voice for eight years near the end of its (first?) run, interviewed hundreds of people for this book. She interweaves all of those interviews, plus other archival material and short excerpts from the relevant articles, with a masterfully light touch. Paragraphs and chapters are short.

Romano touches on every element of the Voice’s coverage, from its lucrative classified ads — both Blondie and Bruce Springsteen hired drummers using Voice personals in 1975 — to Christgau’s “Consumer Guide” record-review column, to film critic Andrew Sarris’s feud with The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael, to the time Stanley Crouch had to be fired in 1988 because he finally slugged a colleague in the newsroom instead of merely threatening to.

Fairly frequently I could hardly believe what I was reading. “She used to do a piece called Yams up My Grannie’s Ass,” arts writer C. Carr says of performance artist Karen Finley. “To tell you the truth I can’t even remember how the yams tied into that.”

In fact the precise disposition of the yams became a subject of debate for much of 1986 in the Voice’s news and letters columns. A lot of the front-of-the-book politics writers, typically older and whiter than the culture writers, were apoplectic that the Karen Finley profile landed on Page 1. They thought it lowered the tone of the place. I’m surprised anyone could be surprised to see anything at all on the cover of the Village Voice as late as 1986, let alone its own writers. “I thought about writing a letter to the Voice,” Finley tells Romano, “but every time I sat down to write, ‘I never put a yam in my butt,’ I’d think, ‘But what if I had? SO WHAT?’”

I don’t recall how I learned that Romano was writing an oral history of the Village Voice and was crowdfunding to meet her expenses. I had never heard of her. It was late 2021, full COVID lockdown days, and I was sending more of my money than usual directly to musicians and other creators to tide them over. When I learned that this person was trying to write a definitive history of the Voice, I thought for a few hours, then sent her a few hundred dollars, enough so she’d notice it had arrived.

She sent a thank-you note. I sent this in return.

“I never went to journalism school. I started reading the Voice in high school because it had the best New York music listings and part of me wanted to be a jazz trumpeter. When I got to university I discovered a complete back collection of the Village Voice at the main campus library. I spent hundreds of hours reading those old copies. This probably contributed to my flunking out of pre-med, but what the heck. Later I became a journalist and I've done pretty well at it. I found out about your project only yesterday and I thought about how much I learned by reading Gary Giddins, Greg Tate, Stanley Crouch, Kyle Gann, Nat Hentoff, Wayne Barrett, Michael Tomasky, Enrique Fernandez, Michael Feingold... I figure I owe them all, so I sent a small portion of what I owe them to you. I've written books, and I know how lonely it can be right through the home stretch. I hope you know it'll all have been worth it. I'm very much looking forward to what you come up with. Best wishes, pw”

This thing I do — the jittery prose style, the readiness to get up and fight now and then, the wide range of topics, so much of my style, whatever it is — it comes as much from reading the Voice as from anyplace else. I started at the back, with the listings and with Giddins’ deeply informed jazz writing, but once you’ve bought the thing and there’s no internet, you might as well keep reading. So like Lucian Truscott I was eventually inspired, instructed, corrupted by the Voice. I viewed my donation to Romano as belated payment in lieu of journalism-school tuition.

Part of the value of Romano’s book is that it’s a reminder of the extended moment — roughly the period between Johannes Gutenberg and Steve Jobs — when printing equipment and technology was just hard enough to procure and use that most people didn’t have it, but it didn’t take unimaginable wealth to leap that barrier either. A few weirdos with a rich cousin or a modest classified-ads business could do it. In postwar America, with so many of the country’s cultural assumptions up for grabs, making the effort became more urgent and rewarding than it had been in decades. (Louis Menand’s sprawling 2021 book The Free World tries to tell the story of that postwar ferment.) It’s no surprise that the Village Voice was founded within a few years of the printing operation at San Francisco’s City Lights bookshop, where Lawrence Ferlinghetti brought the Beat movement to the world by cranking out cheap and cheerful editions of Kerouac, Ginsberg, and others. Operations on both coasts were examples of low-barrier publishing by determined romantics.

By the 90s, the Voice had thousands of imitators in cities around the world, including four alternative weekly newspapers in Montreal alone. A characteristic of all such operations was that they were staffed by people who could hardly believe their good luck. Almost all of those papers are gone now. The technological and financial barriers that made them both possible and valuable have collapsed altogether. Now anyone can publish anything by shunting a few electrons back and forth, and on most days, that’s how it reads.

It’s remarkable how often the people in Romano’s book would learn they had written for the Voice after it had already happened. Plainly nobody here was running a tight ship. In 1965 a longshoreman named Joe Flaherty didn’t like a street protest against Mayor John Lindsay, so he wrote a piece called “Why the Fun Has Left Fun City” for the Bay Ridge Home Reporter. Jack Deacy was at the Home Reporter, and Flaherty’s piece didn’t really suit it, so Deacy dropped it through the mail slot at the Voice. The next Thursday Flaherty’s article was on the front page of the Voice. He still hadn’t been told.

Others knew precisely what they were doing. Mary Perot Nichols was at the Voice when Robert Moses, the legendary New York city planner, was trying to ransack the Village the way he had run roughshod over too many other modest residential neighbourhoods. She also built a coalition of interests to stand up to Moses. With Jane Jacobs, Nichols had a meeting with the local representative of the Gambino crime family.

“He said something like, ‘Why should I care?’” Nichols’ daughter Eliza Nichols recalls. “And my mother said, ‘If that freeway is built, your entire neighborhood’s going to be destroyed. And all those small businessmen who pay tribute to you and who you control are no longer going to exist.’”

Thus do writers learn about power. Usually their words were all the power they needed. In 1969 Jack Newfield heard about how cheap lead paint was killing tenants. In the South Bronx he met Brenda Scurry, whose 23-month-old daughter, Janet, had died of lead poisoning that April. “My day with Brenda Scurry became the launching pad for five lead-poisoning articles I would write over the next four months. I took the subway back to the Voice office and that afternoon and evening wrote five thousand words in the white heat of fresh emotion.” John Lindsay’s became the first city government in America to restrict the use of lead paint.

Many of the stories Romano recounts were familiar to me — the Stanley Crouch fisticuffs, the way Greg Tate goaded the paper to cover hip-hop properly and expanded its readers’ vocabularies with his dense, thorny prose. (From 1985’s “Yo, Hermaneutics:” “Word, word. Word up: Thelonious X. Thrashfunk sez, yo Greg, black people need our own Roland Barthes, man.”)

One of the stories I didn’t know is the tale of David Schneiderman, brought in as the paper’s editor-in-chief by a later generation of owners in 1978, who ended up staying in one management capacity or other for nearly 30 years. Schneiderman was a New York Times man before he came to the Voice. He dressed like it, and the Voice staff were pretty sure at the outset that they didn’t trust him. But he hired and promoted much of the paper’s most talented women, Black and gay writers, partly precisely because the male old guard was too busy giving him side-eye. He ended up defining the paper’s tone and personality for longer than anyone else.

“It didn’t matter where you were when you got there,” Richard Goldstein tells Romano in an attempt to explain the way a button-down Times man came to define the Voice. “Eventually the paper would take you over and change you. This happened to David. The paper altered him, in a good way.” And not only Schneiderman.

This great piece is just one more example of why I have no qualms whatsoever of paying for such content by Wells. What great, readable journalism. Off now to buy the book in question.

“Readers should note that today’s post contains more salty language than usual.” Is there a better way to get someone to read the full article?