People of Ontario! If you make Steven Del Duca your premier, he’ll cut your transit fares to $1. All of them. For a while.

The Ontario Liberal leader’s first campaign announcement came, for reporters, with a backgrounder pointing out that a ride from Kitchener to Toronto on the commuter Go Train now costs $19.40, but that under a (still highly hypothetical) Del Duca government, even that long haul will cost $1. A 95-per-cent savings. That’s the biggest savings the Liberals can identify, though fees would be cut all over, so that, say, a single bus ride in Sarnia would be cut from $3 to $1. The subsidy would end in January, 2024. It would cost a little less than $1 billion this year and a little more next. From whom would it cost these sums, you say? I can tell you’re new here.

At first glance, I hated this announcement. It’s straight out of the Buying Your Vote With Your Own Money And, Worse, Your Neighbours’ And The Future’s file. Having thought about it, I still don’t like it much. But of course, as we’ll discuss, it’s hardly the only policy in that file, nor the Liberals the only party contributing. More than that, buck-a-ride is interesting, and it tells us things about where government is going in this unsettled century.

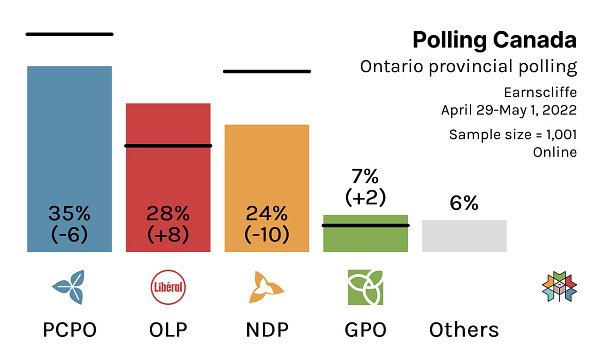

Two points of context. First, Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives have been dominant in the polls for most of their first term in office, but if they slip, there are enough voters who don’t like them to make things interesting. To wit:

Note that much of the drama between now and the June 2 vote will depend on who seems a viable alternative to the Conservatives. The Liberals are doing better than the NDP, but not well enough to relax. So Ontario politics now resembles the joke whose punchline is, “I don’t need to outrun the bear. I just need to outrun you.”

Second, apparently it’s getting really hard for governments all over the place to do the one thing most of them ever enjoyed — building transportation infrastructure.

In Montreal, the second phase of the vaunted REM light-rail network, developed by the Caisse de dépôt public-sector pension fund, has suffered such a severe backlash in public opinion — the rail pylons are ugly, they cut neighbourhoods in half, and the whole thing is transparently designed to steal riders and fares from the subway rather than complementing it — that the Quebec government and the City of Montreal this week ejected the Caisse from managing the project and sent the designers back to the drawing board.

In Quebec City, the provincial government and a spunky new mayor have been bickering over the mayor’s popular tramway and the premier’s unpopular traffic tunnel.

In Ottawa the city, oh God don’t ask.

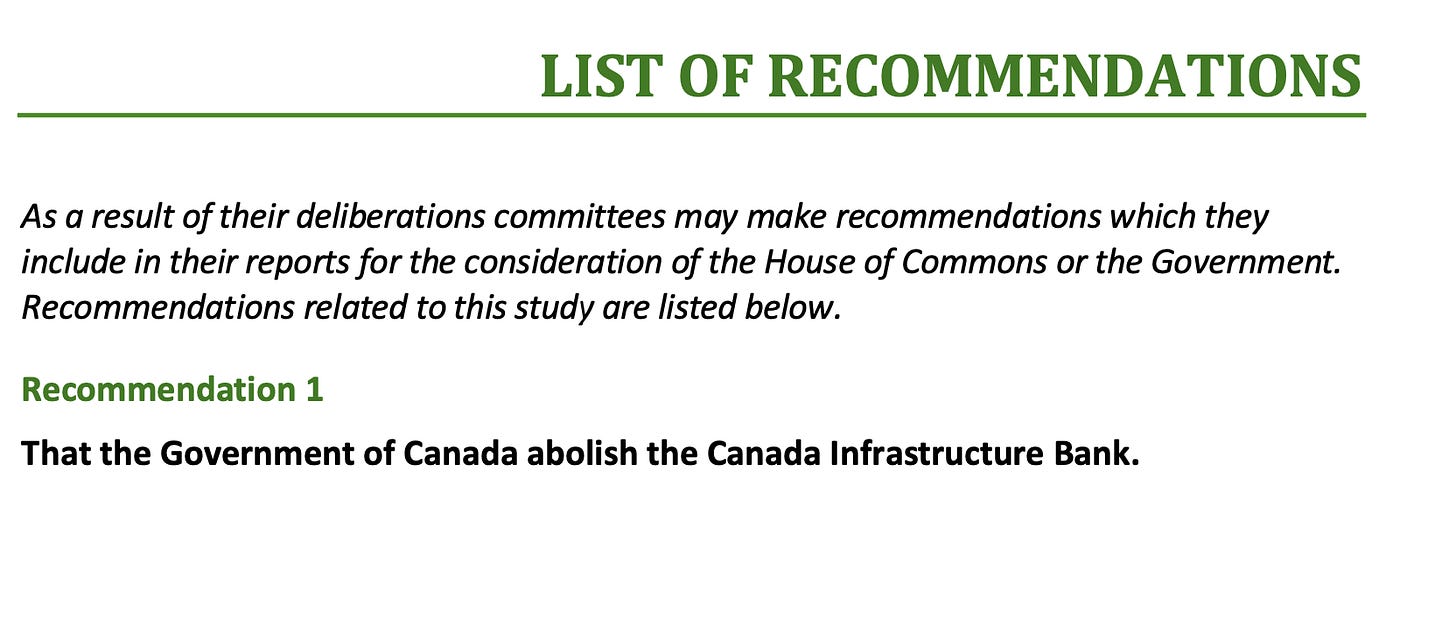

In Ottawa the national capital, the Commons Transportation Committee this week released the report of its study into the functioning of the Canada Infrastructure Bank. I’ll let you read the “Recommendations” page, in its entirety:

Obviously that’s a reflection of the fact that Liberal MPs are outnumbered on the committee by opposition MPs, but still, yikes. If the thing was a hit, the opposition would be competing for credit or playing tug-of-war for windfalls.

It’s within this context that Del Duca, a virtual unknown who lost his own seat in the 2018 election, has to decide how to (a) grab attention early in a three-way race, which is not just a nice-to-have, it’s an absolute need-to-have if he still wants a job in July; (b) maybe, if he’s unbelievably lucky and manages to win this thing, actually hope to get something done.

“Buck-a-ride” is, in the context of problem (a), probably gimmicky enough to help. Let’s concentrate on (b).

What’s not to love about cheaper transit? It offers clear contrast with the Ford Conservatives’ transport centrepiece, cheaper driving. It rings a bunch of classic Liberal bells: it is, or kind of distractedly appears, urban and green, it prizes the collective (many passengers facing the same way) over the individualist (Doug Ford in an SUV), it sure seems to be redistributive, because there aren’t a lot of rich people on the bus.

So why didn’t I like the policy? Because it’s unlikely to work, if the goal is to get people out of cars and into buses and trains. Because if it does work, in that sense, it’s unlikely to be the most efficient use of the next taxpayer dollar (or, in the case at hand, the next billion a year for two years). And because it leaves big problems un-fixed.

That last point was the first in my head. If buses and trains become cheaper for everybody, that doesn’t actually increase transit capacity — it doesn’t put new buses on the road. It doesn’t even put new buses in between the other buses: it doesn’t increase frequency. And a lot of research suggests the choice to take transit has less to do with cost than with having any hope of workable scheduling. A new government would be free to add service while subsidizing fees, of course, but doing both means having fewer funds available to do only one.

What else? Well, this is fun: when transit becomes cheaper, it usually attracts passengers who were walking or riding bikes, not the ones who were driving and whose lives and trajectories are so different they’re much harder to tempt into transit. So cheaper transit might actually have a modest negative impact on public health. While leaving cars on the highways.

But say I’m wrong and cheaper rides do increase ridership. Then we’re back to the question of whether the existing network can handle the traffic, especially since the government just gave away the money it could have used to expand capacity. This might be the only time in the last half-century when that’s less of a problem, because ridership is massively depressed because of COVID lockdowns. So there’s plenty of slack capacity. I do wonder whether government’s job should be to incite citizens to take transit options they are plainly reluctant to take. Also whether that capacity will ever be taken back up, now that some people have pivoted to remote work.

Incidentally, Del Duca’s policy is supposed to end at the beginning of 2024. Who wants to tell people in Kitchener in 2024 that their Go pass is about to become 20 times more expensive?

It’s important to note that the Liberals are hardly the only party in the subsidize-my-electorate game. A highway is a huge subsidy to people who don’t take transit; Ford wants to build more. License plate fees and toll roads are modest attempts to redress the imbalance between driving and transit by asking drivers to pay a fraction of the cost of building and maintaining the roads they traverse. Ford has abolished plate fees and wants to eliminate two toll highways’ tolls.

Each party, then, is simply using massive sums of money from every Ontarian to reward their voter base for being the kind of people they are. I was in my 40s before I owned my first car. Since I left university I’ve never lived more than 30 minutes’ walk from the downtown of a large city. I’ve driven four hours at a time but not often because I’ve never enjoyed it. When Ford “says yes” to drivers, he’s not really talking to me.

This election merely sharpens a longstanding distinction, often seen in regional voting patterns, between city voters and country voters, which is also a distinction between renters and owners, between people who are comfortable doing the same thing as hundreds of their neighbours and people who don’t much like having neighbours, come to think of it. I’m not going to assert particular virtue for either, although getting cars off the road would help in the fight to reduce carbon emissions. If Del Duca’s policy would get cars off the road. Which, in the main, it probably won’t.

This brings me back to an earlier question. Why spend $2 billion over two years for a fee reduction that would leave the actual transit network completely un-improved and, given opportunity costs, probably a little worse off due to deferred maintenance? The answer, I think, is because increasingly in Canada, at every level, when governments spend money on things they don’t get the things they hoped to buy. That was the point of my rogues’ gallery of messed-up infrastructure projects above.

Again, compare and contrast. Ford wants a highway. What he’ll get, in the real world, is an endless hell of cost overruns, technical snags, maybe even the occasional fun court challenge. If Del Duca countered with a new subway, he’d get a similar mess underground. This decline in “state capacity” — the disappearing ability of governments to make anything happen in the three-dimensional world — is a constant theme of discussion wherever wonks gather. It helps explain why the federal government is so leery of buying fighter jets or building ports, and why it has even fallen out of love with visions of high-speed rail. And why Del Duca would rather make it cheaper, temporarily, to ride on a system that isn’t improved. It’s because he’s less sure than his predecessors that it can be improved.

Federal politics these days is not much more than a series of arguments over who should receive which benefits. Del Duca’s choice suggests he thinks provincial government is heading down the same path.

Paul, I'm so impressed with how you keep on top of so many issues and express them to the general public so well.

I for one would read quite a bit more about the diminished "state capacity" we see so widely.

Are there remedies?