1. Hope is hard work

This is the season for hoping things won’t get worse. Everyone who gathered at the Warsaw Security Forum this week knows things are bad. Nobody needed help imagining how they could get worse. But it will be better if they don’t. So the two-day gathering of defence ministers, admirals, academics and think-tankers was devoted, in large measure, to thinking about all the ways things could get worse, and explaining how, really, it was entirely possible that none of these new, supplementary catastrophes will come to pass.

So sure, there’s a wave of populist nationalism sweeping Europe, eroding support for Ukraine. But maybe it’ll stop in its tracks.

And yes, the Ukrainian Army has finally discovered something the Russian invaders are good at — defence — leading to a half-year of stalemate. But perhaps the breakthrough will come tomorrow.

Even if Russia can be pushed out of Ukraine, will it stay out? Or will it decide that an endless low-level harassment campaign across the border — any border, wherever force and fate manage to draw it — will pay dividends of chaos out of all proportion to the investment? Hard to say, but maybe everything will work out.

The most commonly-invoked disaster scenario was that Donald Trump, or some wannabe Trump, will get elected president before the war in Ukraine gets sorted. Surely his administration would abandon Ukraine within weeks after inauguration day. Whether NATO could long survive is an open question. Even here there were optimists. Maybe Trump has changed his mind about… everything. Or maybe a well-informed electorate will teach him the value of NATO.

The latter hope was voiced, improbably, by H.R. McMaster, who was Trump’s second National Security Advisor and whom Trump fired by tweet after barely a year. “The U.S. is not a monarchy,” he said. “It would not be ‘King Trump.’” To which a pessimist can only answer: Why wouldn’t it?

Just about every session at the two-day conference brought its share of revelations. It was news to me that while there’s less Russian natural gas flowing into Europe through pipelines, there’s more coming in by ship.

It’s probably a foolish exercise to try to ascertain the mood at one of these periodic gatherings of people who agree that democracy is worth defending, sometimes with force. (The Munich Security Conference is probably the most prominent such annual event, and the Halifax International Security Forum is a big stop on the circuit, but there are a lot of such events, because the questions they ask — how can conflict be avoided or, if it can’t be avoided, won? — are more or less eternal.)

Sorry, that was a long digression. I was discussing the folly of assigning moods. Let’s assign some. The fall of 2021 was for foreboding — could Russia actually invade Ukraine? The fall of 2022 was for a kind of reckless hope, because Ukraine had effectively, heroically, resisted the attack. The fall of 2023 is for realizing that the hour is still perilous and that good hearts may not prevail. While everyone hopes things won’t get worse, it’s a time to begin to catalog all the ways they might.

2. Ambassador Dion’s list

A few Canadians showed up for the conference, which has been held every year since 2014 in a suburban hotel 20 minutes’ drive from central Warsaw. One was Bob Auchterlonie, the navy vice-admiral who serves as Commander for Canadian Joint Operations Command. In a panel on the maritime dimension of collective defence, he spoke clearly and succinctly about the Royal Canadian Navy’s responsibilities — robust activity in the Baltic Sea, growing obligations in the Indo-Pacific, work in the Arctic that isn’t going away soon. The panel’s moderator, a Polish-Norwegian academic named Jakub Godzimirski, listened to this ambitious list and said, good luck getting funding for all of that.

Another panel featured a familiar face. Older readers may recall Stéphane Dion’s contributions to Canadian democratic life. These days he is Canada’s ambassador to France and Special Envoy to the EU and Europe. There’s a reason for the “EU and Europe” designation. They’re not always the same thing. Another panelist in the room with Dion, Montenegro’s prime minister Dritan Abazović, could testify to that. Montenegro is in NATO but not yet in the EU. Abazović is out of Parliamentary confidence but not yet out of power. He’s an engaging speaker and, probably because he won’t have many chances to address an audience this influential, he spoke a lot. By my count Dion spoke for only five minutes out of a 35-minute session.

This panel’s nominal topic was how the “Collective West” can build partnerships to face “global challenges.” The moderator wondered whether Ukraine is the only such challenge. It sure isn’t, said Dion. “I prepared a list,” he said, digging into his pocket.

I’m going to repeat nearly everything Dion said, simply because I spent so many years listening closely to his public remarks, and wondering how on earth I could convey his meaning to distracted readers, that I slid easily into the old habit.

“Ukraine is key,” he said, peering at his written list of threats. “Why? Because Ukraine is in the nightmare of this war. But [also] for the world, because we want to send the message that a country gains nothing by trying to invade its neighbour. That the crime of aggression should not pay off. It must be very clear. It’s a universal challenge we are facing.”

This was good to hear, a useful corrective, because a former Dion advisor has written that when he was global-affairs minister in 2016, Dion saw NATO’s expansion to the east as a provocation against Russia. Having put down his marker on the Ukraine invasion, Dion started going through the rest of his list. He mentioned “war resurgence elsewhere… and finally the terrible impacts of climate change. But not only climate change. We would have an environmental crisis even if it weren’t for climate change, [because] so much biodiversity is in danger.

“We need to feed, pretty soon, nine billion human beings without exhausting our ecosystems. We need to ensure that access to fresh water does not become a source of conflict. If I had to choose, I would say that water is the issue of the century.”

He continued through his list. “Protecting populations from International terrorism. Halting wide-scale tax avoidance, which is a huge problem that we do not tackle enough. And of course, humanely managing migration flows and trying to mitigate their causes.”

Having issued his partial list of things that are scary even if Ukraine can be saved, Dion offered some thoughts on interpretation. “If I may say… the main challenge we have [in facing] all these problems, is the two definitions of multilateralism that [are] always in tension. One is the Westphalian definition, which is cooperation across regimes — you cooperate with regimes you dislike because you need to tackle problems like these. And the other is the liberal definition of multilateralism, which is the universal declaration of human rights. Each human being on this planet has a right to the same dignity. We need to make sure it will happen.

“So these two definitions of liberalism are in tension, more and more, because we are more and more [interdependent] with regimes we dislike. We don’t like the regime in China but we need to work with China more than ever. So we have a situation where we sanction regimes with which we trade and interact, more and more. That’s the challenge of the time in which we are.”

With that, Dion yielded the floor to the moderator, who collected some thoughts from a third panelist, a junior critic in Britain’s Labour party who will probably be a junior minister if Labour wins the next UK election, as seems likely. Then the caretaker Montenegrin PM, then back to Dion. The moderator asked him something else about the “collective West.” He didn’t like the term, he said, any more than he likes “Global South.”

“These definitions are dichotomizing the world in an artificial way,” he said. “What exists are developed countries that are also liberal democracies. And they are not only in the West. We have Japan, we have Korea, Australia, and so on. So if we talk about these liberal democracies, I see millions of human beings risking their life to migrate to these countries. I see the rich of authoritarian regimes buying properties and making sure that their children are [educated] in these liberal democracies.”

Plainly, developed liberal democracies are attractive places to live and work. And yet “the challenge they have to face is that authoritarianism is a fierce rival. And why is that the case? It’s not only because authoritarian visions have repressive and propaganda capabilities. It’s also because human beings are afraid of uncertainty. And unanimous ideologies are always attractive” because the certainty of an ideology backed by a strong-man regime “may be preferable, in the mind of many people, to the uncertainty of competition of ideas, and parties, and opinions. A strong man will solve the problem.

“And if you have a choice between chaos and despotism, humankind is likely to choose despotism. And maybe they are right to prefer despotism to chaos. So the challenge for us liberal democracies is to convince these populations that between chaos and despotism, there is democracy, which [offers] security to people, but in freedom instead of in servitude.”

He could feel his time running out. “A key thing we need to do, well-established democracies, is to support fragile democracies. And to help them, because they are heroic in their circumstances. It’s not perfect, you have corruption and so on. But they are making progress. And we need to be there to support them.”

Once more around the wheel — panel discussions are an interesting format, I’ve done a million of them, but when you break them down it’s actually striking how little time anyone has to say anything — and it was time for concluding thoughts. Really brief concluding thoughts, because the guy from Montenegro was making the most of his moment.

Not for the first time, Dion showed he can be pithy when he likes. “In a nutshell — in a nutshell —” he said, as the moderator warned him to keep it short. “We sanction the bad guys. It would be a mistake to do only that though. We need to be there to support the good guys.”

And that was the end of Ambassador Dion’s panel.

3. How to rig an election

In 2004, on what must have been a slow news day, I visited Poland’s embassy in Ottawa to interview the ambassador about European Union enlargement. I mean, it must have been a very slow news day. But a big moment was approaching — the largest enlargement in the European Union’s history, 10 countries, perhaps 100 million new citizens in the EU, with Poland by far the largest among the new member states. The ambassador spoke enthusiastically about the economics of it all, but what struck me was how emotional he was. Poles have spent centuries having things done to them. Now they could do this thing. This was what freedom felt like, maybe even what freedom was for.

I went back to the office and looked at a map of Europe and decided these new countries were the future of Europe. Either it would work out, and all would be well, or it would go badly, and there would be trouble. I started visiting the region whenever I could, and preferring Poland, where the food is good, the people friendly, and the history a constant harsh rebuke to anyone in Canada who thinks we have difficult neighbours.

In the end Europe’s expansion to the east has worked out mostly well, with significant bumps. Hungary is the biggest; Viktor Orban’s government rigs all sorts of processes to give his party an advantage over opposition parties. Poland’s ruling Law and Justice party is tempted by similar impulses. Historian and columnist Anne Applebaum provides chapter and verse here. As Applebaum is always careful to note, she’s married to a prominent opposition politician, the former foreign minister Radislaw Sikorski. But her criticisms of the Law and Justice government (its Polish acronym is PiS) are widely shared.

Poland’s had a hard history. It was carved up repeatedly by covetous neighbouring regimes, vanishing altogether as a sovereign country between 1795 and 1918. (All of Chopin’s astonishing music, all those polonaises and mazurkas, was written by a man whose country didn’t exist during his lifetime.) And then along came Hitler and Stalin. There are probably countless possible reactions to that history, but two have dominated Poland’s post-Berlin Wall history: on the one hand, a determination to do better with the great gift of freedom than the country ever could as a vassal state; on the other hand, suspicion and resentment. These impulses don’t map neatly into the country’s politics, but the incumbent PiS government is definitely the standard-bearer for suspicion and resentment.

In 2010 a Polish government aircraft crashed near the Russian city of Smolensk, killing everyone on board, including Poland’s president, Lech Kaczynski, and much of the country’s political and military leadership. An almost unimaginable catastrophe. Investigations by both the Russians and Poles concluded the crash was an accident caused by pilot error, probably under pressure from the VIP passengers. One guy who has never bought that explanation is Jarosław Kaczynski, the dead president’s twin brother. They used to be child stars together on TV. The surviving twin has entertained assorted conspiracy theories about the Smolensk crash ever since. Which kind of distorts Poland’s politics, because Jarosław Kaczynski runs PiS.

What excesses will you permit yourself if you believe your opponent plotted with Moscow to assassinate your brother? Plenty of excesses, it turns out. Poland will hold parliamentary elections next weekend. For the first time since PiS won power in 2015, the party is unsure of keeping its parliamentary majority. The opposition parties have been staging massive rallies. Which isn’t conclusive, because on most days the opposition parties don’t get along, and because it’s easy to round up an opposition crowd in Warsaw, where PiS’s brand of nationalist populism is least popular.

A PiS ad shows shadowy figures in Berlin calling Poland to tell it what to do. A highly resonant image in a country that Berlin invaded more than once, as you can imagine. Jarosław Kaczynski tells the foreign meddlers they won’t have their way because “there’s no more Tusk” — a reference to PiS’s main opponent, the former centre-right prime minister Donald Tusk.

Tusk resigned as prime minister in 2014 to become President of the European Council in Brussels. This makes him a shaky standard-bearer as an opposition leader, because voters who mistrust outsiders are unlikely to warm up to a guy who helped run the European Union. Tusk might as well be on the board of the World Economic Forum or have spent time running the Bank of England. A context-free scrap of video, showing Tusk saying “for Germany” in German, has been pushed out countless times by PiS:

But since merely mocking their opponent might not save them, PiS have found far more outrageous ways to bolster their cause. Voters will be asked to respond to four referendum questions on the same day as the election. The questions are basically variations on, “Do you understand that if we lose the election the country will go straight to hell?” Check it out:

1: Do you support the sale of state assets to foreign entities, leading to the loss of control by Polish women and men over strategic sectors of the economy?

2: Do you support raising the retirement age, including restoring the retirement age increased to 67 for women and men?

3: Do you support the elimination of the barrier on the border between the Republic of Poland and the Republic of Belarus?

4: Do you support the admission of thousands of illegal immigrants from the Middle East and Africa under the forced relocation mechanism imposed by the European bureaucracy?

To say the least, these questions caricature the Polish opposition’s actual policies. But the real value of the referendums for the PiS government is that there is no limit to campaign spending in a referendum, whereas campaign spending for ordinary elections is capped. So the incumbents can blow right past the spending limits, under the guise of “informing voters” about the bogus referendum issues.

I wanted to pass along news of this shell game because it’s so lurid it’s almost funny, and because the way things are going, it’s only a matter of time before somebody in Canada tries something similar. The fight for democracy always begins at home, and its most implacable enemy is the voice in your head that says, the stakes are so high I don’t have the luxury of fighting fair.

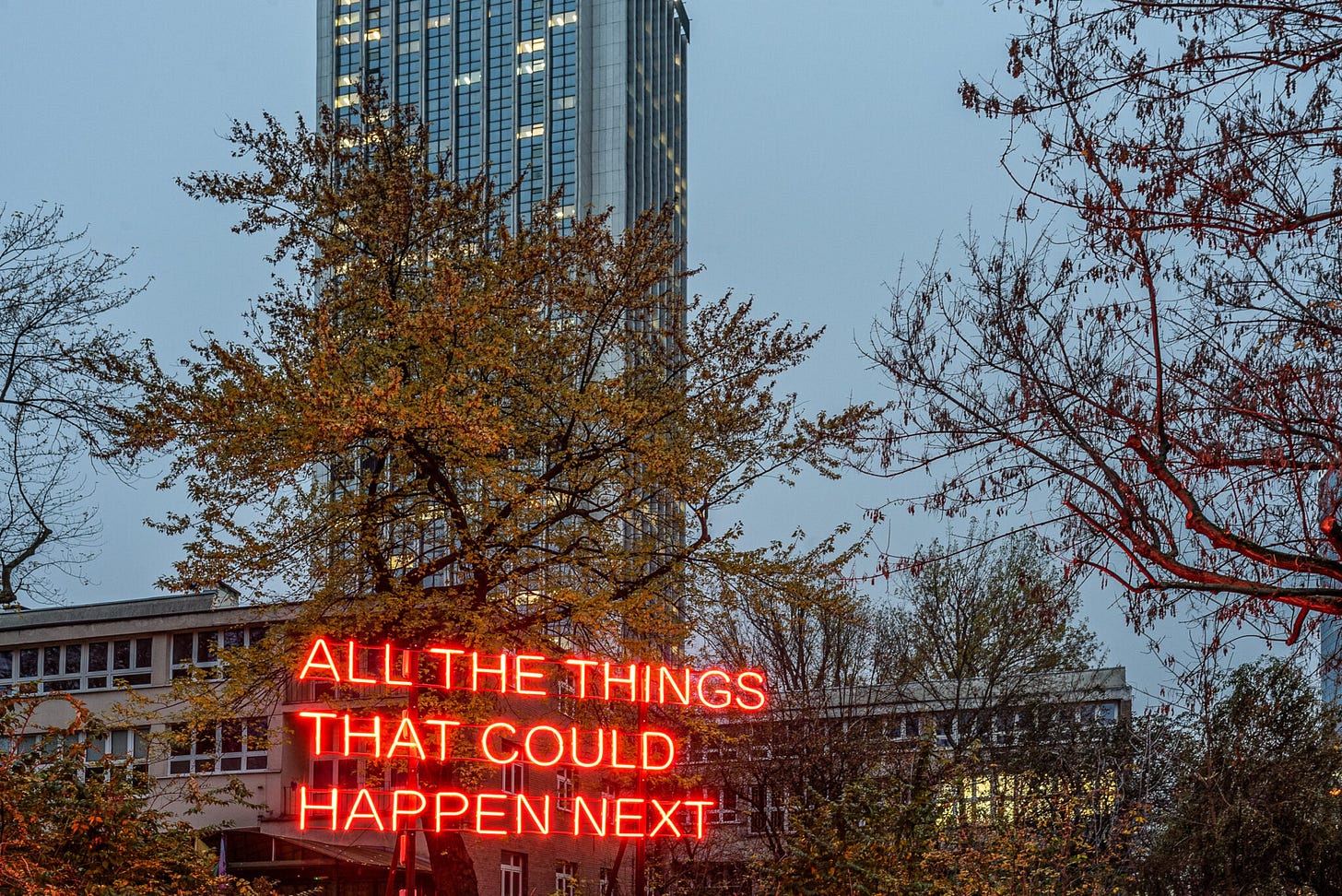

A note on this post’s title: it’s taken from a piece of public art I spotted on my way out of Warsaw. It’s by the British artist Tim Etchells, and I found it rather haunting. As, apparently, he hoped audiences would:

Thanks for this thoughtful piece on a large topic. One doesn’t have to agree on everything in the piece to appreciate that.

Dion is a thoughtful person – perhaps not the most exciting speaker, and perhaps not the most skillful politician. And that’s not necessarily a criticism of him as a person. He may be in the right place at a difficult time.

Your switch from big picture thinking to Polish politics and the use of division and resentment is a big jarring - and the suggestion that, even in Canada, someone will eventually conclude that “I don’t have the luxury of fighting fair”. As we have seen, it has already happened in Manitoba. We can be grateful that it didn't work – and that the winner had the good grace to note that optimism and unity won over attempts to divide, without describing the content of that attempt. The best way to overcome this kind of low behaviour is to overcome it, with grace, and move on.

As with the people at the Warsaw Conference, we can only hope that our good luck continues to hold. But we need to be aware that it might not.

I think the people who think one of the biggest challenges in the world is the fight between authoritarianism vs democracy are a bit stuck in their ivory tower. I’ll talk about Canada here. We are a country where housing (including renting apartments )in most of the country is responsible for a bigger part of people’s salary. On top of that, millions of people dont even have access to a family doctor. Wages seem to be stagnating forcing some people to supplement through gig work. On top of that, groceries keep getting more expensive and inflation keeps taking a bigger part of our monthly budget. So you have a situation where people’s standard of living is either stagnating or declining and the politicians in charge dont seem to care enough to fix this problem.

So yeah, A LOT of people are ANGRY at this happening. So they are going to be more susceptible to so called authoritarian figures who claim will solve the problem. So the fix here would be for politicians who are worried about authoritarianism to try to solve the challenges we face today and to meet some of the expectations citizens have from government.

There used to be a time where homes and renting apartments used to be affordable. If it can be done in the 1950s, it certainly should be doable today. If the current system can improve people’s standard of living, then people will stick with it. If not, then people may shop around for a new one. The response to this shouldn’t be “we need to communicate the benefits of democracy harder” but should be “let’s actually fix the big problems and show people why democracy is still capable of delivering “.