A brain gain, for a change

Chrystia Freeland's budget was full of money for research. What happens next?

Today’s post will be another deep dive into policy details. Sometimes government is about details. Welcome to everyone attending this week’s Research Money conference in Ottawa! Today’s post will interest those folks in particular.

I was in last week’s federal budget lockup but I didn’t write immediately, mostly because these annual events always generate an accidental news glut. When hundreds of reporters hit SEND on stories they’ve been writing all day about the same document, a lot of the coverage tends to run together.

Today I want to live dangerously and talk about a chapter in the budget that’s been well received. Or part of a chapter at least: it’s the stuff on science and research in Chapter 4, Economic Growth for Every Generation.

Here’s what caught a lot of university researchers’ attention:

• The $2 billion-plus that Justin Trudeau announced two weeks earlier on artificial intelligence, especially brute computer processing power. As a few beat reporters were telling us months ago, this is mostly an effort to keep Canada from falling behind other countries on AI capacity, but it still got noticed.

• A $1.8-billion increase in funding over five years for the three main research granting councils: SSHRC which funds social-science research; NSERC in the natural sciences and engineering; and CIHR in health research. After those five years, the three councils will continue to receive a total of $748.3 million more per year than they were getting before this budget.

• a new “capstone research funding organization” to centralize some functions of the three granting councils, and better coordinate the rest. And a new “advisory Council on Science and Innovation… made up of leaders from the academic, industry, and not-for-profit sectors… responsible for a national science and innovation strategy to guide priority setting.”

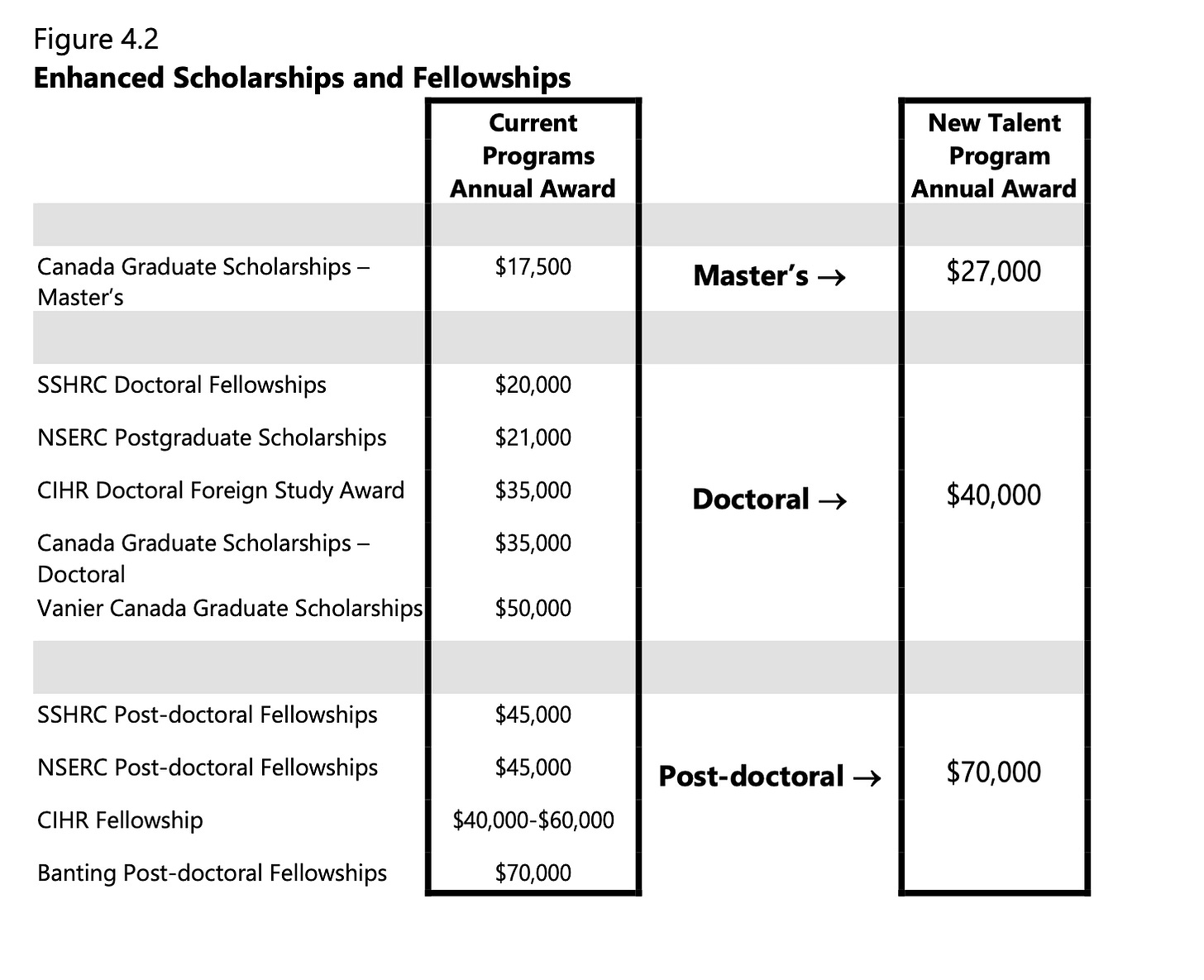

• Finally, substantial increases in government pay for most graduate students and post-doctoral researchers working in university labs. This is a response to the most extraordinary sustained outburst of protest against the Trudeau government from the country’s young researchers. Here’s their angry response to Freeland’s 2023 budget. They’ve now entirely changed their tune. Here’s the new pay scale:

I’m going to get into the political analysis of all this below. But what people who follow research policy noticed is that the measures I’ve listed here closely match the recommendations of a 2023 report from Frédéric Bouchard, the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at the Université de Montréal.

I was the first journalist to write about Bouchard’s report in any detail. There haven’t been many others since. My post on the report was probably read by more people in the government than Bouchard’s report itself was. The government originally hoped few people would see the report at all: Bouchard’s panel, with seven university administrators from across the country, was created in October 2022 with orders to report only two months later, confidentially. Bouchard was also invited to make recommendations about the structure of all these granting agencies, but not about how much the feds should spend.

The report was finally released a year ago, four months after Bouchard submitted it. He simply ignored the order to say nothing on funding. He called for funding to SSHRC, NSERC and CIHR to increase 10% a year for five years. And for the feds to pay grad students and post-docs better. And for the feds to set up a new advisory body.

In the end the feds have delivered a little less than half of what Bouchard advocated for the granting councils, and basically everything on grad-student pay.

As for the new advisory body, we’ll see: As Bouchard himself pointed out in his report, the government used to have a “Science, Technology and Innovation Council” made up of deputy ministers, university presidents and business leaders. It was set up by Stephen Harper’s government and shut down by Trudeau’s. True story. After an earlier advisory panel under former UofT president David Naylor made recommendations much like Bouchard’s five years earlier, the Trudeau government announced the creation of a new “Council on Science and Innovation” in 2018. They even launched a search for the new thing’s chair.

There has been no update from the government on the creation of this new body since 2019. It simply vanished. A cautionary tale for anyone who might celebrate the arrival of a new Council on Science and Innovation (or the same one?) five years after we heard from the last.

So: More money for AI, which is essentially a cost-of-keeping-Canada-from-losing-ground move; big incremental money for investigator-led research, for the first time since the 2018 budget; and the latest promise of organizational change to encourage “strategic” decisions instead of decisions driven by polls and PMO sugar highs. This is a substantial improvement, for those of us who think Canada should support research as steadily as the US, UK and Japan do, over the feckless 2023 budget, which Alex Usher called the worst for universities since 1995 or 1996.

Now a few considerations of politics.

First, you can’t really hang your hat on five-year plans announced one year before an election. Less than 13% of that big boost to granting-council funding is scheduled to be delivered by 2025-26. So 87% is hanging out there in the mandate of another government. That doesn’t mean it’s fictional: anything announced in any budget is incorporated by the Finance department in the spending track, which is the set of assumptions on which future budgets are based. A future government run by this PM or by his opponent would have to decide to spend less on granting councils than what was announced in this year’s budget.

This budget, like budgets everywhere every year, was full of these multi-year spending rollouts. Which is why Pierre Poilievre’s reaction has largely consisted of wishing the Trudeau government would simply stop making budgets. Every decision now constrains the manoeuvring room of any prime minister later. Even if a (still hypothetical, but work with me) future Poilievre government maintains this budget’s schedule for spending on science granting councils or anything else, some people will say he wouldn’t have done it if his predecessor hadn’t locked it in.

Second: what’s so great about the granting councils, and why have successive governments been reluctant to put research money into them? Related: Why did Bouchard and Naylor put so much emphasis on a high-profile coordinating body for research decisions, and why has this government spent nine years not creating such a thing?

Basically I’m describing a tug of war. Scientists believe the best decisions about which science to support are made by scientists, through peer review. They’re not making decisions divorced from everyday concerns — how can we cure cancer, or speed up computers, or build useful new materials? — they’re just making those decisions based on what’s most promising for technical reasons, rather than what sounds good for marketing reasons. As we’ve often heard, Geoffrey Hinton’s research was getting supported by granting councils 30 years before politicians wanted to associate themselves with him.

Governments these days — all governments — like to tell an essentially heroic story about themselves: We’ll get cancer cured, we’ll build houses, we’ll make things better. They are increasingly skeptical of a bunch of strangers in lab coats who say: Give us ever-increasing amounts of money, and we’ll make it work out for the best. Somehow. When governments do turn their attention to questions of research, intermittently, they are tempted to announce a new program with a defined end: Alzheimer’s, “democratic decline,” what have you.

Government interest is, almost by definition, fitful, intermittent, unpredictable and prone to self-contradiction. That’s why scientists would like government to make as few decisions as possible. That’s why they keep asking for some sort of strategic advisory board.

Lately I’ve been urging scientists to better understand why their requests for ever-increasing amounts of money with ever-decreasing government oversight sound so bizarre to governments. So Freeland’s decision to cede so much to the research community (urged, I’m sure, by Industry Minister François-Philippe Champagne) is surprising. Here’s what I think happened.

First, the researchers have a point. Investigator-led research works in unpredictable ways, but it often works in concrete ways with lots of zeroes attached, as I wrote in the most heartfelt article I’ve ever written about this stuff.

Second, I think the government has been surprised at how pissed off researchers are becoming. I’ve simply never seen a news release from Universities Canada like the one that followed 2023’s budget. For years the Trudeau government’s response was, “what are you gonna do, vote Conservative?” Lately I suspect they’re unnerved by the silence that follows that question.

Finally, I think the proximity of an election is precisely the point. Governments often like to announce things when they’re at risk of losing an election. If it doesn’t help them win, it makes trouble for a future government. The Ontario Liberals never had to run a francophone university for Ontario, they just had to promise one and watch Doug Ford twist.

So sure, there’s a chance that Freeland’s 2024 budget will be a problem for Chrystia Freeland (or Mark Carney, whatever) in 2027. There’s a bigger chance it’ll be a problem for Finance Minister Rachael Thomas. Do you think Pierre Poilievre wants to spend billions on AI servers? Or literally double government paycheques for 30-year-old social scientists?

So there’s a paradox here. It’s clear that Frédéric Bouchard’s report changed the conversation about science policy in Canada. And I think this budget is intriguing evidence that François-Philippe Champagne can push a file uphill. But scientists have been pleading with governments for years to think less about politics. All the same, I suspect this windfall arrives now because this government is thinking as much about politics as ever.

Nice to see research money....but since the actual big time research labs created under Paul Martin were trashed by Harper.....it's just been political outhouse whistling since.

At the risk of sounding repetitive:

I have been travelling a lot this year and my friends that I visit are mostly Boomer Liberals and NDP types....and they just can't stand the the sight or the voice of the present PM....to the point where no announcement including the budget matters anymore, except the one that says he's leaving... if he doesn't, thereby taking with him PP's biggest talking point - the Liberals are toast, PP gets 200 seats and all those tinfoil hat People's Party types get to talk about their version of science...

As much as this article makes me happy (Thanks, Paul)...I just can't shake the fact that Canada is in a drift - either the PM and Co. have never answered the question "Where do you see Canada in 5 years or 10?"...or I have just quit listening...

...and before you comment, yes I know that PP has not suggested any future at all for the country ....

You nailed it - on many dimensions.